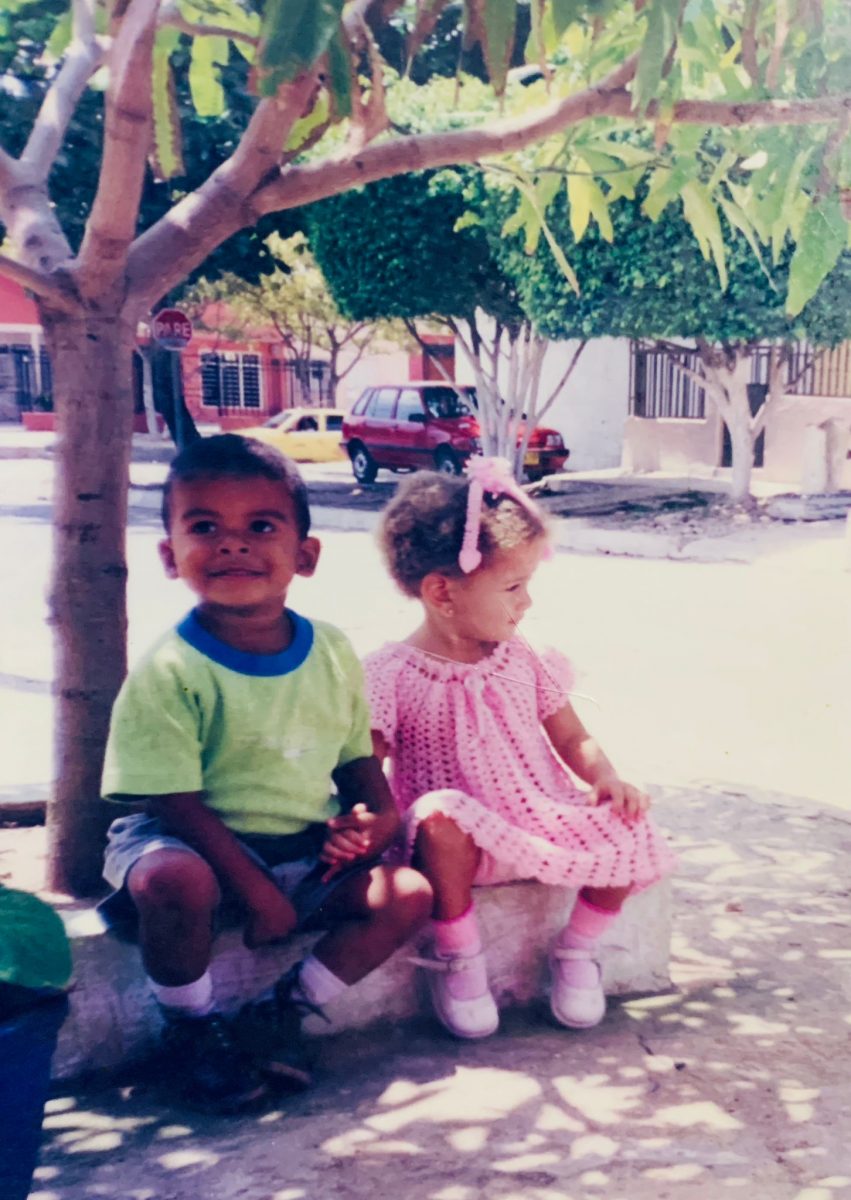

Image: © Erika Castrillón Morales

Author: Erika Castrillón Morales

[Content warning: animal sacrifice]

Every April, we climbed the mango tree. It was on the terrace of the house I grew up in. Green-yellowed leaves decorated its arms, but the mangoes were always late, or they never arrived. We climbed and played in its branches, hoping not to fall. I used to slide my little fingers through the crackered bark to peel the cortex. If you were lucky enough, you could make tiny balls with the tree’s resin to play with. All the kids in the neighborhood loved that tree. Every one of us had a story to tell about it.

***

In August 1976, Antonia Villalba moved to Barranquilla, a bustling and noisy city like all the ones in the north of Colombia. She was a tall, pale, rounded woman, strong, and bulky. She came from Bogotá, the capital, or ‘la nevera,’[1]as we called it in the Coast for its cold weather. Too cold for people accustomed to more than 34 degrees Celsius in a tropical country. Antonia had also lived and worked in the countryside of Santander, for many years. Well accustomed to the hard work, the woman knew how to ride a horse, how to raise a family, and specially, how to cook with gifted hands. After my grandfather died, my thirteen-years-old mom took control of the house. To have an income that could ease the hunger, she began renting out some rooms in the family’s household. Antonia moved in with her three kids and her parents. Her husband, a truck driver, had died in a traffic accident. She decided to move to Barranquilla, where an estranged cousin had settled in the city and also married a truck driver.

Antonia always loved to earn her own money; she juggled between jobs to take care of her family. Having set up a small convenience store in our house, she started selling roasted food. Antonia bought the goods at the market. Early in the morning, she got on crowded buses, filled with people from various backgrounds: employees, foreigners coming from nearby areas and small villages, domestic workers, salespeople, merchants, and another informal workforce. Successful businesspeople, public servants and doctors never took the bus, they took taxis or drove their own fancy vehicles. The market was a conglomerate of people coming from all over town. You could find city halls and offices next to hospitals and food stands, decorated with long queues of people waiting to enter any of those buildings. Street sellers offered bracelets and rosaries in the middle of copious fragrances. The odor of smoked fish appealed to those craving a hearty breakfast after running errands for a while. If you were looking for something lighter, you could try a buñuelo with hot coffee. The city was, and still is, a living being in which all citizens acted like organs making the body function. At 9 am, Antonia was back home with big bags of fresh vegetables and groceries to sell. José, her eldest son, had already started serving customers.

Weekends were special as she set up plastic tables and chairs on the terrace for people to come and eat. The tables were nicely dressed up with floral pattern coverings and embroidered ends. On Fridays, she came from the market with a goat kid. During the afternoon, you could hear the poor animal howling when Antonia killed it. She then made pepitoria[2] to sell or some roasted goat on Saturdays. She also came with roosters. She plucked the chickens and seasoned them with a red paste made with bell peppers, onions, achiote and salt. She then put the chicken on grills and sold them with salty potatoes. Of all the food she made to sell, she always gave some to my mom. Sometimes Antonia gave even more than what she owed her in rent. In the end, it was a transaction based on solidarity.

On Sundays, Antonia made a humongous soup pot, a sancocho. She knew her cousin spent Sundays with her husband’s colleagues and their families. Antonia invited them to come around and buy her some soup. They accepted the invitation and were all delighted with the food and friendly time. It then became a tradition to have lunch at our house on Sundays to enjoy the roasted chicken, goat or soup, or any other exquisite dish that Antonia made, thinking about her old Santander. Those dishes included in every stir or cut the traces of nostalgia.

Antonia’s youngest son was a little boy called Juanito, five years old, and there wasn’t any difference between him and a Tasmanian devil. He looked just like his mom, and he was born just before his father’s passing. He ran around the house, playing in the dirt and driving everyone crazy. That boy was pure chaos, but sometimes, he was lonely. His mother was busy making some money, so she could not watch him all day. His siblings had school or were helping Antonia. The boy’s loneliness and sadness grew more and more evident. Antonia felt guilty about her son, so she came one afternoon with a puppy to keep Juanito company. They called it Zeón. Juanito and the dog were very alike, messy, and dirty. With its tender eyes, the creature captured everyone’s smiles and caresses.

One Sunday, it was the birthday of one of the truck drivers. Antonia woke up early, as she anticipated many people that day. She had promised them to make the best sancocho one had ever tasted. An array of potatoes, sweet, and green plantains, calabaza, yam and cassava. Gallina criolla and carne salada, a meal which ‘industrial’ could never define.Word about the famous soup spread all over near neighborhoods. At 7 AM, Antonia had already cut all the vegetables for the soup. The meat had been soaking in spices overnight. José started piling firewood in the backyard. Antonia carried the pot and put it in the fire. The smell of the smoke flew around the houses. People passed by in their Sunday best and said hello to Antonia on their way to the Mass.

That day Juanito was more restless than usual. As a tornado, he ran with the dog from here to there in the house while Antonia kept asking him to stay still. Giving up, she told him to go out and play with the neighbor’s son. Juanito took the dog with him.

José was sitting next to the pot to make sure it wasn’t going to burn. When the soup was ready, José put a lid on it and went to help his mother with another task. It had already been a while when Juanito and the dog came back. They started running and playing around the soup pot. Suddenly, a clattering noise and a pitiful bark resound in the backyard. José heard Juanito’s laugher, and he knew something was wrong. He went running to see what happened. Shocked, José cried for help “¡Mamá, mamá, Juanito tiró el perro en la sopa!”[3] Luckily, the soup was no longer boiling. Antonia, shaking nervously, hurried up to take the dog out of the soup while menacing Juanito with a beating. Juanito, seeing that his mom was not joking, ran as fast as a runaway puppy. With his short arms and legs, he climbed the mango tree. He then waited at the top, looking at the bottom where Antonia held a heavy belt. We also had stories concerning our mothers’ belt.

Antonia yelled “¡te me bajas inmediatamente de ahí, culicagado!”[4] She was furious. Her pale face turned red with anger. At the corner of the street, the trucks’ honks were loud. People arrived on foot and some others getting out of taxis and private cars. It was too late to start cooking another soup pot. And how could you explain such a mischief? Antonia gave Juanito a last look. “¡Te bajas, o te bajo, y ya verás!”[5] The boy got out of the tree. His mother grabbed him by the ears and ordered Teresa, the middle sister, to clean and dress him up. José took the dog and gave it a bath.

People came into the house and warmly greeted Antonia. Everyone took a seat. Teresa started serving the delicious-looking soup. Plates were passed from hand to hand, with lemon slices and rice. Pepitorias, arepas and some aguapanela were served. They were laughing and making jokes. Through the radios, some Vallenato and Cumbia were heard. Someone took a bottle of aguardiente and made a grimace at its bitter taste. It was a festive and happy Sunday in the Colombian coast. After quick belt strokes, Juanito continued to happily play with the dog. But away from the soup. The guests kept coming for more soup and more rice. What an amazing cook Antonia was! Everyone who attended the party that day kept talking about it for months; years passed, and everyone remembered Sundays at Antonia’s. But no one dared to say: ¡Esta sopa sabe a perro![6]

[1] Spanish word for fridge.

[2] Colombian dish typical of the Santander Department made from the goat’s entrails, blood, and hard-boiled eggs.

[3] “Mom, mom, Junito threw the dog into the soup.”

[4] “Get down, culicagado” (Colombian slang word for a little kid, usually a mischievous one).

[5] “Get down or you will see.”

[6] This soup has a doggy taste.

Comments by the jury:

“I think it was a lovely rendering of a funny anecdote through adult eyes; it’s very self-aware and socially-driven”

“I appreciated the details of the food, how she made it and what she used in the recipes. … I was thankful that the dog survived its encounter with the soup!”