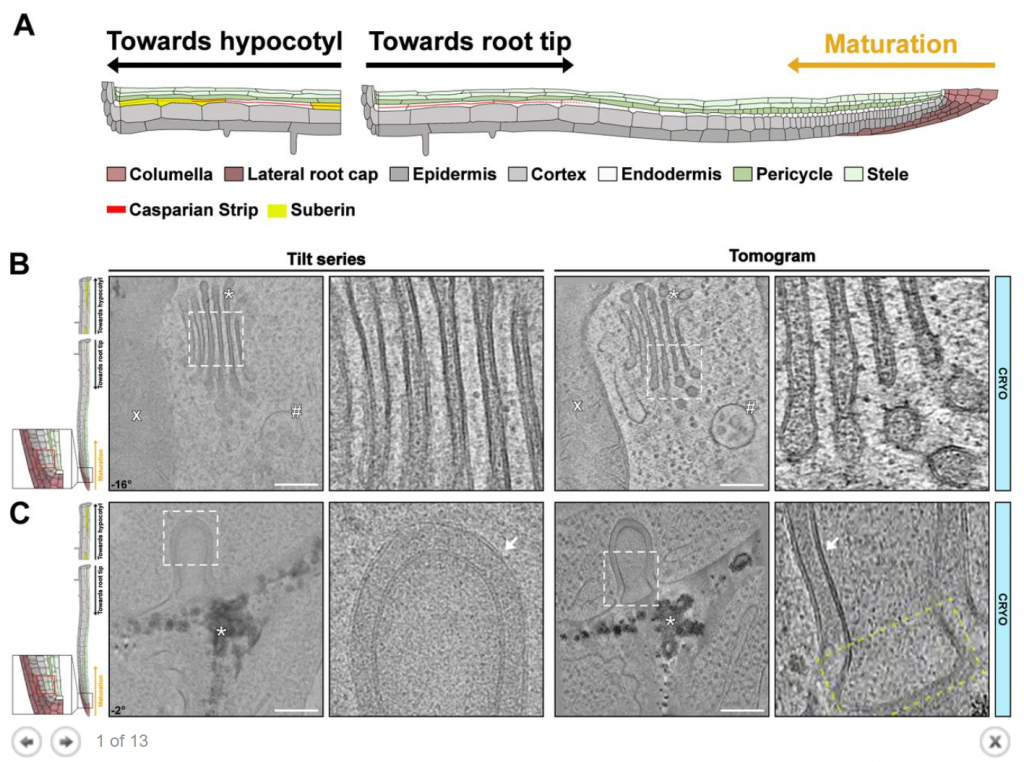

- The article Targeted imaging of specialized plant cell walls by improved cryo-CLEM and cryo-electron tomography is published in Nature Communications! It is a perfect example of synergy between the EMF that is providing the technical expertise and a research group that has a biological question to answer. In this particular case, the group of Niko Geldner accepts to embark in this technical development. It is the most efficient way for a research group too run an ambitious project at EMF. We are happy to welcome and train researchers in the frame of commonly founded projects! Such « embedded researcher » are becoming the only way to tackle challenging projects in Electron Microscopy.

- Thanks to generous donators, the iFLM is installed on our Aquilos 2 cryo-FIBSEM. It allows to visualise the fluorescence in the sample inside the chamber of the microscope in cryo-mode. We expect that it accelerates our pipelines, diminishes contamination and improve the cryo-CLEM accuracy!

- The Apreo for Volumescope and array-tomography is installed at EPFL. It is part of a R’Equip where researchers from Unil participate by proposing projects. the EMF team is trained to use it and we are beginning to run projects requiring large 3D volume or array tomography. Such an optimization of the ressource between Unil and EPFL is an asset for the researchers !

Happy to share our new preprint

Happy to share our new preprint

Jean Daraspe and Etienne Bellani pushed the limits of serial lift-out in order to observe the Casparian strip in the root tip of Arabidopsis thaliana. Have a look if you want to discover our new workflow on the platform for cryo-CLEM and cryo-ET.

If you are passionate by the structure of plant root tip, it is also an article for you!

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.06.01.657137v1

Nature protocol

New article in Nature Protocols : we are happy to be able to share this article with all of you!

We hope it will help researchers to find rare features in tissues that cannot be genetically tagged…

Join the BioEM facility of Life Science Dpt, EPFL

Join the BioEM facility of Life Science Dpt, EPFL

Graham Knott and his team are looking for a new colleague!