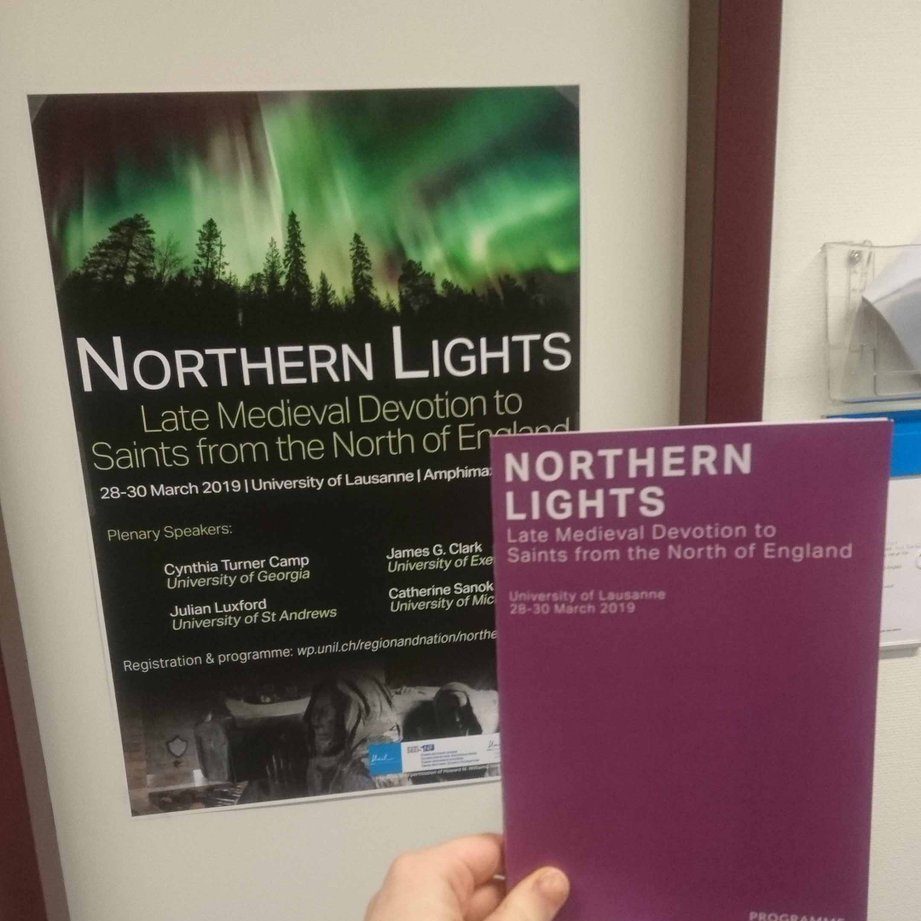

Last month, while visiting family in the UK, I decided to spend a few days in northern England investigating local celebrity and medieval hermit St Robert of Knaresborough (c. 1160-1218). St Robert’s cult is the subject of my PhD thesis, which is part of a wider project on northern English saints funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. While much of the material relating to St Robert exists in literary form, a surprising amount of information about his life can be gleaned from artistic, archaeological, and architectural sources.

A medieval hermit’s cave

My first stop was the cave in which St Robert lived, located on the northern bank of the River Nidd in Knaresborough. Cut into the side of a limestone cliff, under a canopy of trees, this little hermit’s hideaway can be accessed via a narrow set of stairs leading down from nearby Abbey Road.

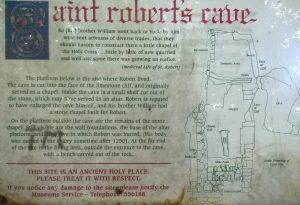

Robert led a solitary existence in this cave, and according to the Middle English metrical version of his life, he spent his time here ‘in contemplacion nyght and day.’ Concerned about Robert’s well-being, however, his brother Walter sent workmen to renovate the saint’s home, building him a chapel with living quarters attached to cave’s entrance sometime around the turn of the thirteenth century. The foundations of this chapel are still clearly visible, and more detailed information about the site’s archaeological make-up is available on a nearby interpretation board.

One of the areas highlighted at the site is the oblong grave which would have been set before the chapel’s high altar. This is where Robert was buried, so both the cave and chapel remained intimately connected with him long after his death. The complex attracted throngs of pilgrims during the Middle Ages, and would once have been filled with colourful images and devotional offerings to the saint. Robert’s body was later removed and re-interred at the nearby Trinitarian priory. Today, all that is left of the chapel burial site is a stony grey outline of the former tomb, though, rather strikingly, some bright green flora has sprouted (or has perhaps been planted) at the eastern end of the grave.

Stained-glass windows

Crossing the River Nidd and venturing south into Derbyshire, my next stop was St Matthew’s Church in Morley, where I was greeted by church historian and archivist Sheila Randall. Over a cup of tea, Sheila and I talked about the scenes in one of the church’s northern windows, where episodes from Robert’s life are detailed across seven late-medieval stained-glass panels.

The window tells the story of St Robert and the deer. Sick of them ruining his crops, Robert petitioned the local lord to sort the problem and the lord gave Robert permission to enclose the deer in a barn. Exerting miraculous power over the wild animals, the saint rounded them up with ease, so impressing the the lord that he allowed Robert to keep them. Demonstrating further mastery over the animals, Robert harnessed them to his plough and used them to work the land.

The panels are not original to St Matthew’s church; they came from nearby Dale Abbey with a variety of other medieval treasures. And as H M Colvin notes, the window was restored in the 19th-century, the result being that, alongside most of the inscriptions, panels 1, 4, and 7 are modern (and not entirely accurate) representations of the original medieval glass. Sheila took care to point out where the glass had been cut to fit its new home, and the panels now sit directly above a mosaic of medieval floor tiles probably also from Dale.

The origins of the abbey are closely linked with the tale of another medieval hermit, a baker from Derby, whose own cave was situated on a hillside not far from where Dale was founded. The abbey’s connection with the story of St Robert remains obscure, though Brian Golding suggested that the canons there may have been interested in the legend of the Knaresborough saint on account of its parallels with the story of their own hermit-founder, who, like Robert, ran into problems with local landowners.

Dale Abbey fell into disrepair after Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, though the magnificent remains of its east window arch attest to the medieval building’s previous grandeur.

A modern celebrity

St Robert captured the attention of medieval writers and artists alike, and his legacy is closely intertwined with modern Knaresborough’s civic identity. Alongside the cave linked to early-modern soothsayer Mother Shipton, and the remains of Knaresborough Castle, St Robert’s cave is one of the town’s top tourist attractions. Further information about the saint can be found in a flyer available in the castle gift shop, and this booklet includes instructions on how to reach his cave on foot.

On the final day of my tour, I ventured into York itself – the city in which Robert was born. No trip to York is complete without a visit to Bettys tearooms, and it was here, while I sat reflecting on my visit, that I learned of another exciting connection between Yorkshire and Switzerland besides our SNSF project. Bettys – that famous local Yorkshire institution – was founded nearly a century ago by Frederick Belmont, a Swiss confectioner!

Hazel Blair

Doctoral Researcher

The images featured in this piece are copyright of the author, who is indebted to Sheila Randall of St Matthew’s Church in Morley (Derbyshire) for access to the St Robert window and permission to photograph it.