Travelling from Switzerland to Vienna at the end of March to present my recent research on St Oswald of Northumbria, King and Martyr, at the International Medieval Translator conference, I felt that I was bringing a very English, even nationalistic, story of sanctity to Vienna. The seventh-century king is famously credited with effecting the Christian conversion of Northumbria by summoning missionary assistance from St Columba’s monastic community on Iona.

Provided with Bishop Aidan, Oswald travels with him around his kingdom, reputedly translating his Irish sermons into Anglo Saxon. By the same token, Aidan lauds Oswald’s charity to beggars and predicts his future saintly incorruption. Bede celebrates Oswald as a Christian warrior-king, a kind of English Constantine, waging battle to vanquish the pagan and bring Christianity to the north. Ambitiously and ambiguously, he describes Oswald’s rule extending over ‘all the peoples and provinces of Britain’ (Historia ecclesiastica, III.6), seeming to see in him an ideal of Christian kingship for England.

I was interested, not only in the story of Oswald as a regal translator into Old English, but also in the translation of his Life into Middle English in the late thirteenth century, in the South English Legendary. Scholars have long detected a nationalistic flavour to this legendary, and it is certainly the case that Oswald becomes more English and more southern leaning within it, his contacts with Irish Christianity and South West Scotland minimised, and his northern head-relic cult expunged in favour of his east midland veneration at Peterborough.

So, this was a tale of royal English sanctity far removed from both the Swiss cantonal systems of governance, where I began my journey, and the imperial Habsburg grandeur of Vienna, where I got off the plane. Or was it ? Bede and the South English Legendary play up Oswald’s national credentials, but in fact his cult is remarkable for its rapid dissemination into mainland Europe. Willibrord, the Northumbrian missionary known as the ‘apostle to the Frisians’, brought Oswald’s cult (and reputedly his head relic) to Echternach in modern-day Luxemborg by the early eighth century. By the eleventh century, further relics were venerated at the Abbey of St Winnoc in Flanders, and at Weingarten in Bavaria, and by the High Middle Ages his cult was being celebrated all the way from Iceland in the north (where we find a late ‘Osvald’s saga’), through the German-speaking lands of central Europe, into Poland and Hungary.

More particularly, in relation to my own European travels, it turns out that Oswald of Northumbria is also an inhabitant of the Swiss canton and city of Zug. Yet another of St Oswald’s several heads reputedly made its way here, and his iconography retains pride of place in the magnificent late fifteenth-century St Oswald-Kirche.

Nor have I left Oswald behind in heading for Vienna. In addition to the prose legend of Oswald’s Northumbrian churchbuilding and eventual martyrdom on the battlefield, cherished in England, there is another continental story about Oswald in which he exports his military zeal abroad, splices it with romantic fervor, and sails to the Middle East to fight a pagan king for the hand of his Christian daughter. All kinds of fantastical elements find their way into this narrative, including a talking raven who carries letters and love tokens between the two lovers. This story exists in several vernacular versions, including the ‘Vienna Oswald’, a substantial fourteenth-century poem in the Silesian dialect, in which Oswald is re-identified as the King of Germany. As well as participating in what is essentially a crusading romance, Oswald and his raven clearly catch the popular Austrian imagination, and the king is venerated in sites across the Tyrol as a patron saint of agricultural plenitude who works together with his raven to ensure favourable weather.

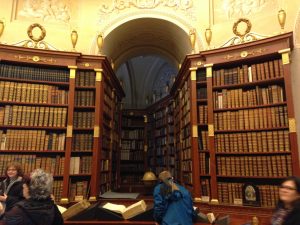

All this seems a very long way from the Oswald of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica. But on my last day at the conference, joining a trip to the spectacular Augustinian monastery of Klosterneuberg, just outside Vienna, we were granted access to a selection of the manuscripts from its medieval library, still the largest private library in Austria. There, staring out at me from an enormous Latin legendary, was Oswald once more, abbreviated but intact – back in the form in which Bede presented him, and intriguingly surrounded by a sprinkling of other Anglo-Saxon saints as well as the normal continental throng. Time is too short to digest this find properly – I’ll have to go back and take another look! What are all these Anglo-Saxon names doing in this central European legendary? How will Bede’s Oswald have been experienced in a milieu apparently more familiar with his repurposing as a crusading suitor ?

Whatever the scholarly answers to these questions, they leave me reflecting on the way in which this apparently most English of royal saints overflows his regional and national boundaries, and bursts joyously onto the continent in new guises and genres, multiplying heads and avian helpmates as he proceeds. There is really no such thing as a straightforwardly regional or national saint; cults show a protean ability to endlessly reconstitute themselves. Despite attempts to commendeer them to nationalism, they have an uncomfortable habit of popping up behind enemy lines. The story of Oswald in Europe demonstrates how one country’s saint becomes another country’s saga hero or crusader, and how vibrantly creative and productive those transformations can be. In our current milieu in which national boundaries are being reasserted around the world (and history often abused in the process), Oswald serves as a timely reminder of a regional and national icon who is also, through many towns and vernaculars, a fully assimilated European!

Christiania Whitehead

Head Reliquary of St Oswald, 1170s, Hildesheim Dommuseum