Guest blogger Antoine Willemin reports on the English Department’s trip to northern England in February 2017.

Last February, just before the start of the spring semester, a small group of BA and MA students from the English Department of the University of Lausanne made their way to the North of England for a study trip organised by both linguists and medievalists, the first of its kind at UNIL. From the shores of the Irish Sea to the banks of the River Tyne, this week had us listen, see, explore, and experience many facets of the land, from historical, literary, and linguistic perspectives.

Coming from Manchester, Liverpool, or London, we all met up in Lancaster to start our journey through the North. After a visit to the campus of Lancaster University (a UNIL partner institution), featuring lectures on the poets of the Lake District and discourse analysis, as well as a tour of their linguistics labs, we took the road to the city centre to visit its medieval priory church. There, Clare Egan, lecturer in medieval and early modern literature at Lancaster, introduced us to the wonderful – if not Reformation-proof – sculpted misericords of the choir stalls, and to the wider history of Lancaster and Lancashire through the lens of its representation on several historical maps.

The following morning saw us on the road through the Yorkshire Dales, finally arriving in York in time for lunch and a brief trip to King’s Manor, the old seat of Henry VIII’s Council of the North, to listen to a lecture on the history of the city by Professor Sarah Rees Jones from the University of York. After touring the impressive Minster, famous for its preserved – and Reformation-proof, this time – medieval stained glass, we finally made our way into the city’s medieval streets, meeting for dinner in one of their many pubs.

York was perhaps an ideal place to illustrate the historical and linguistic intricacies of Northern England: Norse influence pervades the city, which was called Jorvik by its Scandinavian settlers. To this day, the name of its streets all end in ‘gate’, from Micklegate to Stonegate, a word derived from the old Norse gata – meaning street.

The following morning we developed this idea with a lecture by UNIL linguistics specialist Professor Anita Auer on the historical urban vernacular of the city and its many specificities. This was accompanied by a lecture by Professor Denis Renevey on multilingual literary production in medieval Yorkshire, featuring devotional texts in English and Latin, and an introduction, by Dr Christiana Whitehead, to the history of several northern saints, from Saint Aidan and the founding of his monastery on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne to Saint Cuthbert and the transfer of his cult and relics from Lindisfarne to Durham, which we visited the next day.

First, however, was the bus ride to Newcastle, where we stayed for the rest of the trip. Here we discovered an entirely different North of England, made of bustling cities marked by the industrial revolution. That night, as if to mark the contrast with York and its medieval streets, we attended a performance of Pride and Prejudice at the city’s Theatre Royal, a beautiful neoclassical building built as Newcastle became more prominent in the 19th century.

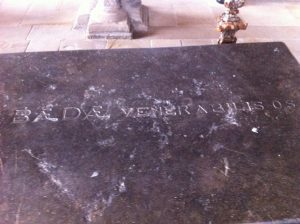

The next day, however, we returned to the Middle Ages with a day-trip to Durham. This small city would not look out of place in Switzerland: built on a hill in a meander of the River Wear, it bears a striking resemblance to the old towns of Bern or Fribourg. At the top of the hill stands the imposing Norman cathedral, the final resting place of Saint Cuthbert as well as of the Venerable Bede – a logical pilgrimage for English literature and linguistics students!

After a tour of the building, which offered a striking contrast to the perpendicular Gothic of York Minster, with its Romanesque arches and massive engraved pillars supporting its stone roof, we headed to Palace Green Library to view a wonderful array of manuscripts from the university and cathedral libraries.

After so much focus on the medieval North of England, our last full day in Newcastle pulled us right back to the present with a visit to Newcastle University, where linguists Dr Adam Mearns and Dr Danielle Turton introduced us to the specificities of the northern English we had been hearing for the past week, and more specifically to the dialects spoken around Northumberland.

Determined to turn us into proper field researchers, they sent us out on the High Street, for a riff on Labov’s famous department store experiment. We spent the afternoon running from Primark to Fenwick, from John Lewis to Waterstones, gathering data to determine which way of saying yes prevailed in the city, and whether it depended on the social status, gender, or simply the age of the speakers. As it turns out, the expected ‘aye’ is becoming less common, but the full ‘yes’ is actually far from the norm: most people, whatever their social characteristics, tend to go for a simple ‘yeah’.

The last day of the trip was perhaps the most packed: after an early check-out, we travelled northwards to Lindisfarne, the Holy Island, beating the tide to cross the causeway, where we spent a long morning exploring the site of the Benedictine monastery established by the chapter of Durham Cathedral on the site of Saint Aidan’s original monastery, which had been abandoned after the first Viking raids on the island.

Coming back down south, we finished our journey at Jarrow Hall, formerly called ‘Bede’s World’, to learn more about the life of the venerable historian. The museum featured exhibits and archaeological finds from Jarrow Monastery (where Bede studied and worked), displays on early-medieval stained glass, as well as a reconstituted Anglo-Saxon farm and village, complete with farm animals of heritage breeds and wattle and daub buildings.

Exhausted but happy, we parted ways at Newcastle Airport as the afternoon ended, some of us boarding our flights back to Switzerland, while others stayed behind to extend their trip in Newcastle and beyond.

Antoine Willemin is an MA student in medieval English literature at the University of Lausanne.

Header image: Detail from the late medieval Gough Map (Bodleian Library, MS. Gough Gen. Top. 16), showing northern England.