Few things have caused me to reflect on the relationship between personal, regional, and national identity so much as my decision to leave the United Kingdom to do my PhD. It was not like going on holiday; I was filled with excitement, but I was also very nervous. The closer I got to my destination, the further I felt from home. What on earth had I let myself in for?

I knew I was one of thousands of students across the centuries who had chosen to leave the British Isles in order to study in mainland Europe. I also knew that Lausanne had hosted a wealth of successful British writers and scholars, including Edward Gibbon, with whose Decline and Fall I am familiar. And, more generally, I knew that Scotland had forged strong links with Switzerland during the Reformation.

But while these facts were of interest to me, when I stepped off the train in Lausanne I felt little initial connection to the new space in which I found myself.

I’m pleased to say that things have since changed. Ironically, it is my home country – the far-away geographic area with which I identify the most – that has brought me closer to Lausanne. Almost every new person I meet asks me where I’ve come from and, here in Switzerland at least, my answer is always ‘Scotland’.

If you were to ask me the same question on British soil, I might reply differently – there, my identity as a Glaswegian would almost certainly come to the fore. I do use the adjectives ‘British’ and ‘European’ to refer to myself from time to time, but while abroad it is my identity as a Scot that seeps from every pore.

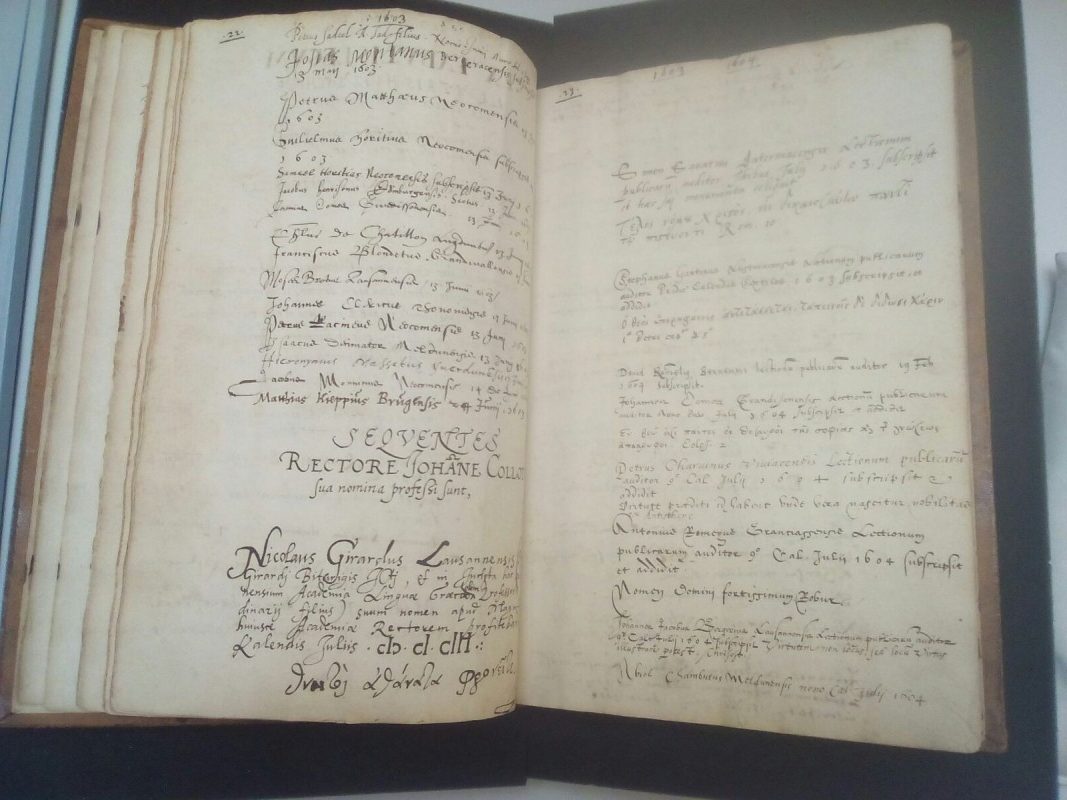

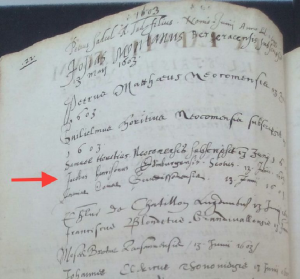

So, looking for a more personal link to my strange new home, I decided to see if I could find any Scots in the University of Lausanne’s earliest matriculation register. The majority of early students, it seems, were either Swiss or French, but, scanning each page of the centuries-old manuscript, I spotted a more familiar surname.

Scribbled under the date 1603 were the details of one Jacobus Henrison, a man from Edinburgh who registered at the Academia Lausannensis, as the university was then known, in June of that same year. This makes Henrison one of the institution’s earliest scholars, the university having been founded as a Francophone school of Protestant thinking in 1537.

It might sound strange, but, burying my identity as a Glaswegian, I felt comforted seeing this Edinburgh man’s details inscribed in the pages of an early manuscript produced in the institution with which I had just become affiliated.

All of which begs the following questions: am I Scottish, Glaswegian, British, or European? Am I ever all these things at once, or will context always force a lead geographic identity from me?

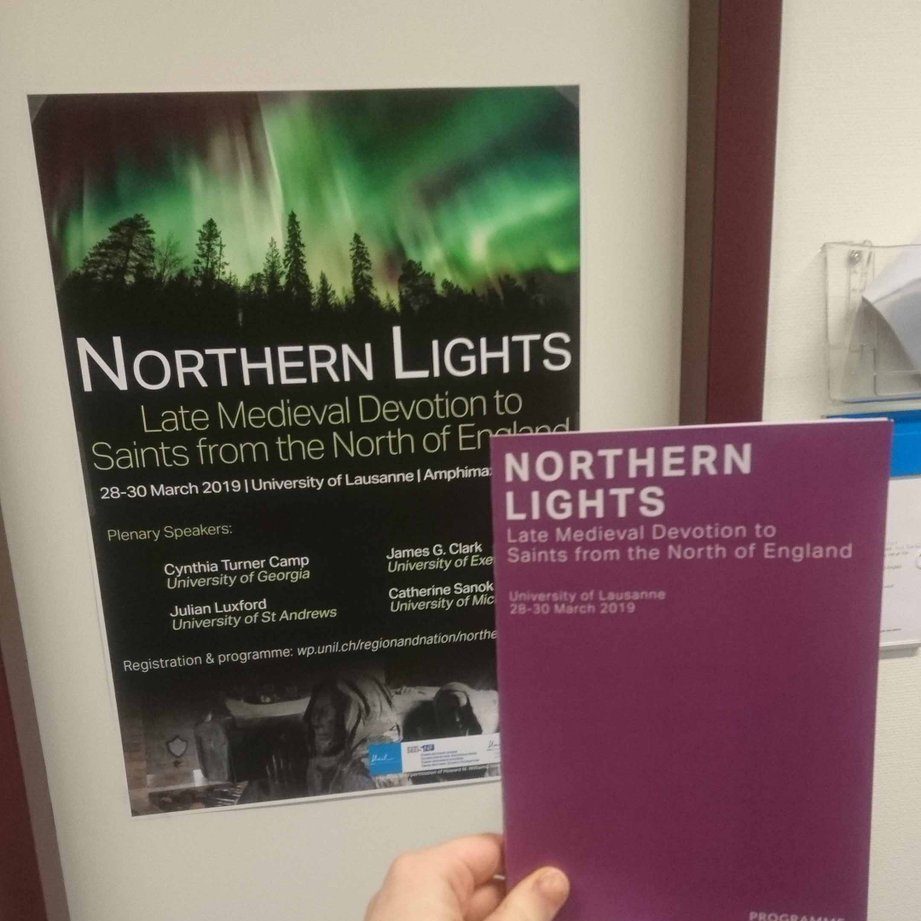

In Scotland, as in Switzerland and northern England, strong regional traditions sit side-by-side with nationwide celebration and collective national sentiment. And so it is the fluid nature of identity in relation to region and nation that I will bear in mind as I begin work on this project.

Hazel Blair

FNS Doctoral Researcher

The main image shows Album Academiae Lausannensis (1602-1819), Archives cantonales vaudoises, Bdd 106, ff. 22v-23r. Images reproduced with the kind permission of the archive.