Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

How did the Earth’s continental crust form and transform over geological time?

This question about the beginnings of our planet’s fundamental dynamics remains hotly debated. Jack Gillespie, who has just taken up his post as Ambizione fellow1 at the Faculty of Geosciences and Environment (FGSE), is keen to unravel this mystery.

How do you infer a history of over 4.5 billion years?

Jack Gillespie: I am an isotope geochemist. Using the isotopic composition of rocks, I try to understand what they have experienced – the geological processes they have gone through over the course of their long history. Thanks to these “tracers”, I’m working to resolve a question that keeps nagging at me: was the early Earth similar to the one we live on? Or was the early tectonic environment profoundly different from today’s Earth?

“We know so little about the origin of the planet we live on.”

Jack Gillespie

Why are you interested in early Earth history?

J. G.: The scale of our ignorance is immense. We know so little about such a vast period! That’s what I find so compelling. And the further we go back in time, the greater the challenge, as our archives are increasingly small and fragmented. The most ancient rocks we have are 4 billion years old. For the first 500 million years, we simply don’t have any intact rock.

Now, how can you meet the challenge of jumping into the distant past?

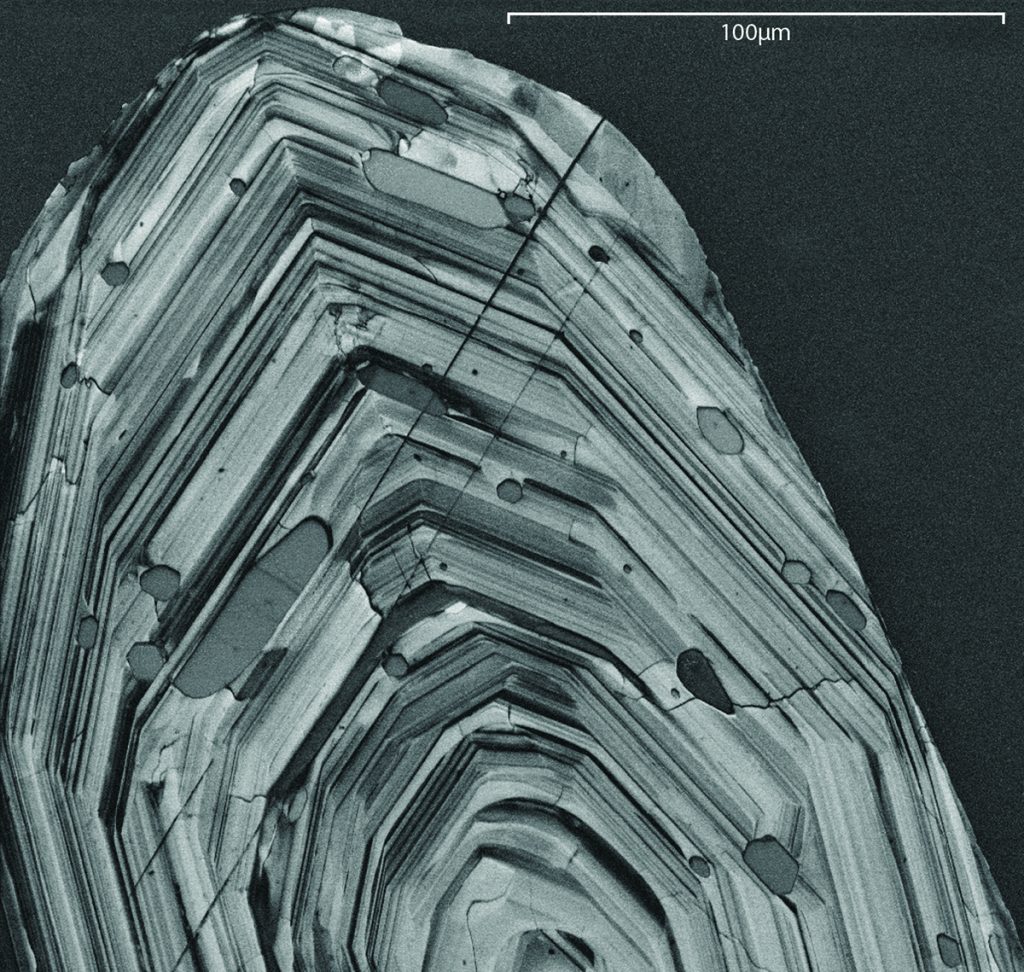

J. G.: Today, we can “do more with less”. We’ve improved both our conceptual understanding and our technical abilities. So we can examine a very small volume of material and extract more information out of it. Just a few decades ago, geologists had to reduce and dissolve down large chunks of rock to derive geochemical insights.

My project synthesizes and brings together a bunch of powerful advances to develop new tools that can meet this challenge.

“The conditions that prevailed during the formation of a rock leave different signatures in the minerals. We’re deciphering them to try and reconstruct these conditions.”

Jack Gillespie

What did early Earth look like?

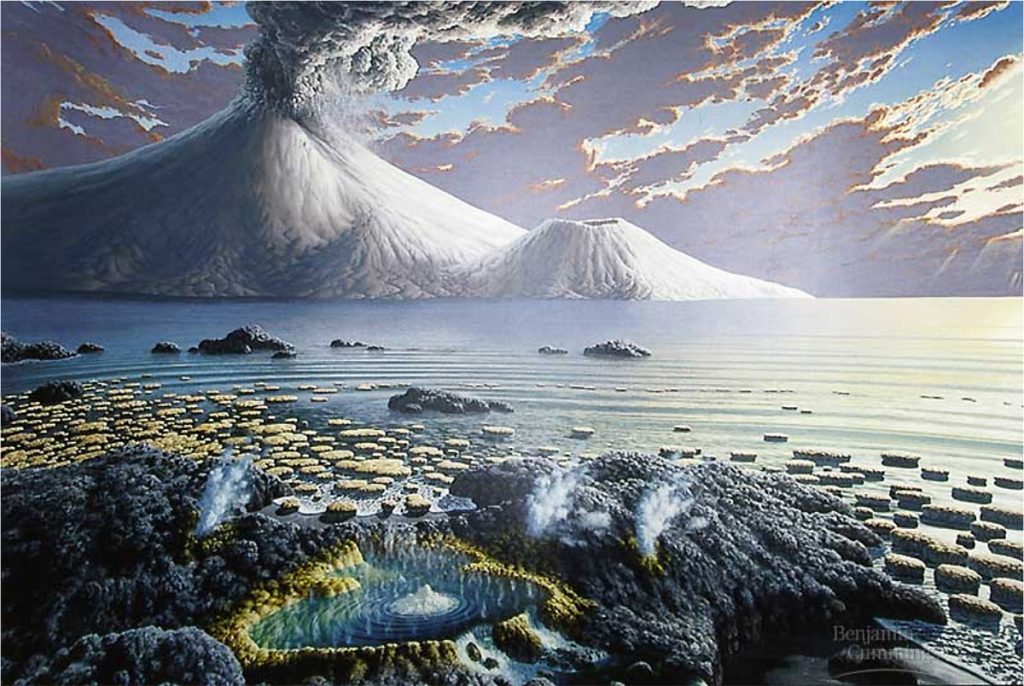

Was it a hellish period, as the name “Hadean” suggests, in reference to the god of the underworld, Hades? This is a somewhat outdated idea, and we’ve known for some time that this wasn’t precisely the case. But the nature of the primary landscapes and the forces that governed them during the Hadean and the Archean remain uncertain. Some emphasise a violent and eventful history for the early Earth, such as is illustrated on the left, with burning skies and meteorites crashing everywhere.

Others would argue the more peaceful vision on the right, with its placid volcanoes and bodies of water is more faithful to reality. This scenario is compelling, with the hot pools at the edge of the land identified as a good place for the first hatching of life.

Why did you choose the FGSE for your Ambizione?

J. G.: Several groups at the Institute of Earth Sciences (ISTE) are raising questions about early Earth, and our approaches will enrich each other. Johanna Marin Carbonne is working on the link between the atmosphere, the oceans and primitive continents, and the processes that led to life and oxygenation of the atmosphere. Othmar Müntener is interested in the creation of the earth’s crust.

The SwissSIMS ion probe is ideal for what I want to do: measuring tiny features and extracting information from it.

Links

- Jack Gillespie

- ISTE Research pole Geochemistry and Petrology of Earth Systems

- Ambizione est une bourse carrière du Fonds National Suisse, à destination des jeunes chercheuses et chercheurs (dans les quatre ans suivant l’obtention du doctorat) qui ambitionnent réaliser et diriger un projet de manière autonome. Les subsides sont octroyés pour une période de quatre ans. ↩︎

Leave a Reply