Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

A new peri-urban park was born in the Jorat woods in 2021, becoming the second of its kind in Switzerland.

Pascal Vittoz (IDYST) is involved in the initial monitoring of this forest, which is entering a new phase following the complete cessation of logging. How will this forest landscape, a favorite walking spot for Lausanne residents, evolve over the next 50 years? The first milestones have been set, and now we’ll have to let the forest give us the answers, at its own pace.

Armed with a map and a compass, Pascal Vittoz ventured through the thicket in search of the plot he was to survey today. A traverse through the brush reveals an area dominated by spruces. These conifers, planted in the 19th or early 20th century because of their rapid growth, are still predominant today. Without human intervention for economic reasons, this area would be covered with fir and beech today.

How will the forest, its wildlife and its inhabitants evolve in the future? That’s what this study is all about. Pascal Vittoz is in charge of monitoring the flora, in particular the undergrowth, in order to study the consequences of the creation of the forest reserve on floristic diversity. These surveys will be carried out every 10 years, in collaboration with a commissioned botanist, Loïc Liberati, former student at FGSE (Faculty of Geosciences and Environment) and Patrice Descombes, former student at FBM (Faculty of Biology and Medicine), and current curator at the Lausanne Botanical Garden. They share the 132 monitoring points randomly distributed throughout the forest plots, according to a plan drawn up by the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL), with the aim of observing the future of the forest.

The new Jorat Natural Park aims to encourage the presence of dead wood. With it, certain birds that burrow into old trunks, beetles whose larvae feed on wood and fungi that decompose dead trees will flourish. One part of the forest – the central zone of the park – will remain untouched for the next 50 years: no cutting, no logging, no off-trail passage. It will simply be left to its natural evolution, with the exception of a few necessary cuts to ensure trail safety. In the transition zone further south, towards the Chalet à Gobet, logging will continue as before, but certain measures will be put in place to promote biodiversity and welcome the public.

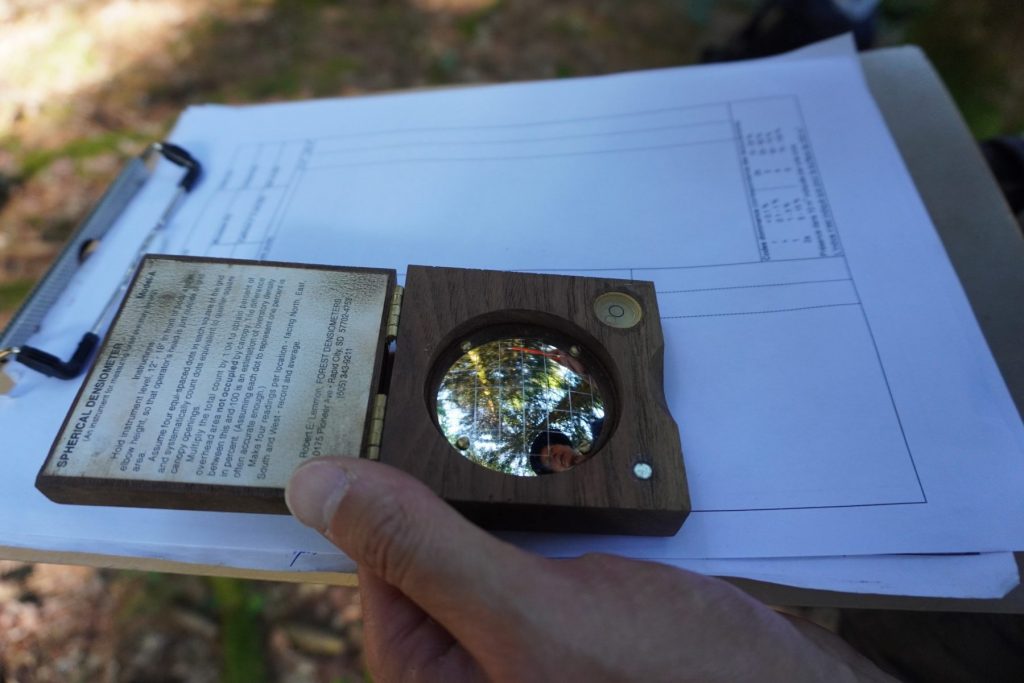

In each plot, the botanists examine two concentric surfaces around the point selected at random by WSL. They describe the structure of the forest and list the flora in the herbaceous, shrub (less than 3 meters high) and arborescent (more than 3 meters high) strata. This gives us an idea of regeneration: if a tree type is present in all strata, it has a good chance of remaining in the future forest.

The botanists draw up a complete inventory of the flora in two concentric zones, starting from a central point marked on the photo by a blue stake. The first disc, measuring 10 m², corresponds to the standard used for biodiversity monitoring in Switzerland. The second, measuring 200 m², gives a more complete picture of the undergrowth flora, providing a better description of forest structure, such as tree size and proportion of dead wood.

A beetle trap suspended in the middle of the plot bears witness to the various monitoring activities carried out by other groups of scientists. To explore the future of the forest, regular surveys are carried out to study its uses (pedestrians, bicycles, horses) and fauna (beetles, batrachians, deer…).

After logging ceases, we can expect the trees to age, leading to a denser, darker forest, with less light reaching the ground and therefore fewer plant species in the undergrowth. However, the vagaries of storms and climate change make predictions difficult. Spruces, for example, could suffer from the heat and be partly decimated by attacks from the bark beetle. In a conventional forest, foresters cut down affected trees to contain their proliferation. But what will happen when there are no longer any health checks on the trees? Will the bark beetle spread further? Will their presence favor species other than spruce?

« This reserve is set up for 50 years, which is more than half a human lifetime, or about ten times a standard research project. » Pascal Vittoz

So we’ll have to wait to see the benefits of this park materialize. Typical research projects are planned to last 3 to 4 years. In this case, that’s not long enough to study forest flora, which evolves very slowly. This study, which spans the entire lifespan of a tree, will not deliver its results for several decades.

What do botanists find in the Jorat woods?

(photo : P. Vittoz)

The forest is dominated by spruce and beech, with undergrowth often lacking in plant diversity. However, some wetter areas, such as ash groves, offer surprises and less common species. Horsetail, a common species in the Alps but much more widespread on the Plateau. Horsetails are among the oldest plant species, having appeared nearly 400 million years ago. Some species were important trees in the Carboniferous period, while today’s largest representatives grow to around 1 m.

More informations

- Parc du Jorat Website

- Pascal Vittoz Website

Leave a Reply