Following the success of the Cuthbert’s Treasures exhibition back in the summer at Durham Cathedral, the end of the November sees the opening of another important new exhibition: Saintly Sisters (28 November 2017-3 February 2018). Exploring saintly women from the north of England, this exhibition is largely, though not exclusively, focused on Anglo-Saxon holy women, revisiting well-known figures such as Hilda of Whitby, and restoring other more obscure early saints to visibility.

One of the most renowned Anglo-Saxon female saints, Etheldreda of Ely (c. 630-79), has early associations with Northumbria which this exhibition brings back into relief. Born into a royal household in East Anglia, her second marriage to King Ecgfrith of Northumbria brought Etheldreda to the north where her saintly inclinations began to reveal themselves in her insistence upon a chaste marriage. Eventually granted permission by her husband to live as a nun, she was professed at Coldingham (now in Berwickshire) at the double monastery founded by St Aebbe. She later returned south, founding a monastery at Ely. After her death, her body was found to be incorrupt and reputedly miracle-working, and her shrine became one of the most popular pilgrimage destinations in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman England. The exhibition describes ‘St Etheldreda’s chains’: coloured necklaces of silk which could be purchased at her cathedral fair annually in memory of the neck tumour which caused her early death.

Despite her friendship with St Cuthbert and mentoring of Etheldreda, St Aebbe (615-83) is a more problematic figure, not least because, soon after her death, Bede relates how her monastery at Coldingham was burnt to the ground as a sign of God’s displeasure with the sexual misdemeanours of the monks and nuns there. Nonetheless, after Coldingham was refounded as a Benedictine priory in the late eleventh century, and colonised with monks from Durham Cathedral priory, there was a need for a local cult. Consequently, Aebbe’s coffin was fortuitously unearthed by shepherds, and taken to the priory where it began to work miracles. Not long afterwards, Aebbe appeared in a vision to a local layman and instructed him to build an oratory in her honour on St Abb’s Head.

Initially, the reluctant visionary did nothing about it, and Aebbe retaliated by rendering the land infertile. After he complied, she began a posthumous healing ministry and seems to have specialised in healing women: she is particularly known for restoring the voices of women stricken with dumbness. The exhibition shows us a Latin legend of Aebbe in the early sixteenth-century nationalistic legendary known as the Nova Legenda Anglie, and charters issued by Coldingham Priory.

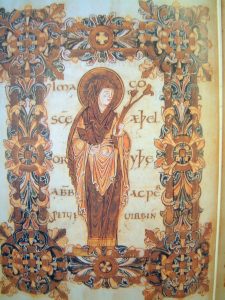

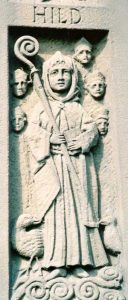

Cuthbert found further female friends amongst the nuns and abbesses of Whitby monastery. The most famous of these, Hilda (c. 614-80), plays a prominent part in the exhibition. Her textual legacy is represented by a late medieval copy of Bede’s Historica ecclesiastica, which relates most of the near contemporary information that we have about the saint – her founding of a series of monasteries, most famously Streoneshalh (Whitby), her presence at the Synod of Whitby, and her patronage of the lay brother Caedmon, the legendary father of Old English religious poetry. An extract from Sir Walter Scott’s poem, Marmion (1808), affords us a glimpse of later legends that grew up about Hilda. Reputedly, her nuns at Whitby were terrorised by a plague of poisonous snakes and didn’t dare leave their cells. Hilda boldly prayed to God to rid them of this pestilence, and the snakes immediately turned tail to the sea shore, coiled themselves into spirals and turned to stone. This story, which was certainly known by the fourteenth century and probably much earlier, is an imaginative myth of origin for the ammonite fossils that can still be found on that coastline. The exhibition includes some of these fossils from Whitby, creatively named Hildoceras in honour of Hilda and her legend.

Another little-known saint from the north is described in her thirteenth-century Vita as a close friend of Hilda. St Bega, a somewhat mythical seventh-century Irish princess, evaded an arranged marriage in Ireland with the aid of a magic bracelet, then sailed across the Irish sea in a coracle and lived in religious reclusion in Copeland, Cumbria. Subsequently summoned by St Aidan to be professed as ‘the first nun in Northumbria’, she travelled east, leaving her bracelet which later became a wonder-working device in its own right. She founded a monastery at Hartlepool, and this was later passed on to Hilda. Shortly after, she re-emerged (possibly a conflation with another Begu) as a nun at Hackness, the daughter house of Whitby. Here, one night, she heard a bell ringing and was granted a vision of St Hilda’s soul being carried up to heaven by angels (Hilda had died that night, many miles away in Whitby). Although Bega’s cult never really took off on the north-east coast, she was venerated enthusiastically in the north-west, at Holme Cultram and St Bees, where her bracelet continued to defend the interests of the priory until late in the Middle Ages.

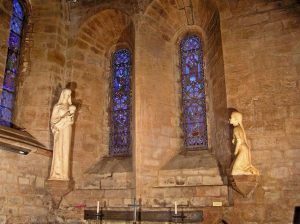

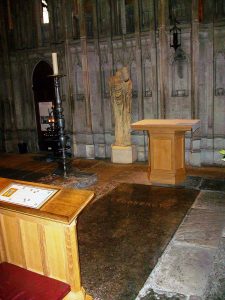

Despite the presence of these enterprising seventh-century abbesses and female hermits, and St Cuthbert’s friendships with several of them (the exhibition also mentions other abbesses of Whitby), events took a more misogynist turn at Durham Cathedral in the late eleventh century. After a new cohort of Benedictine monks were brought in to tend Cuthbert’s shrine there, monastic historians began to circulate stories about Cuthbert’s antipathy to women – partly, it is supposed, to protect the purity of the monks. New miracle stories graphically portrayed what happened to women who strayed onto Cuthbert’s cemeteries or into his churches – very few lived to tell the tale. A strange blue line of marble inset into the floor of the cathedral near the west end, and still there at the beginning of the sixteenth century, seems to have acted as a kind of boundary marker, prohibiting women from advancing any further into the cathedral.

Since female pilgrims were a lucrative source of income, it made no sense for them to be discouraged from coming to the north altogether. St Godric of Finchale, a twelfth-century hermit whose cult was controlled by the Durham monks, may have been deliberately developed in a way which countered that difficulty. Skilled at transiting female souls from purgatory to heaven, and receptive to visions of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalen, Godric’s shrine seems to have specialised in healing services for women, and to have attracted unusually high numbers of female pilgrims for a male saint.

Despite the misogyny of the medieval cathedral, some of the most intriguing displays of the exhibition concern the female groups who emerged from it and were supported by it in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Society of Christ and Blessed Mary the Virgin (SCBMV, founded 1884) was a body of volunteer nurses, later ordained as deaconesses, who ran almshouses and mission houses in the county for more than sixty years. Labelled ‘daughters of St Cuthbert’, these women seem to have lived a quasi-monastic life, wearing Cuthbert’s pectoral cross around their neck, following a daily routine of prayer and abjuring marriage. The exhibition unearths documents, artefacts and atmospheric photographs associated with these forgotten ‘daughters’.

Durham cathedral may have regulated and restrained the desires of female pilgrims for several centuries before the Reformation, but this exhibition offers a powerful northern counter-narrative by bringing to light multiple Anglo-Saxon and modern stories of saintly founding abbesses, wonder-working female hermits, and charitable deaconesses, who continue to inspire and challenge viewers into the present day.

Christiania Whitehead

FNS Senior Researcher

Saintly Sisters will run from 28 November 2017 to 3 February 2018. Tickets range from £2.50-£7.50 and are available from the Visitor Desk in the Cathedral, the Open Treasure Welcome Desk, and in advance on the Cathedral website.