This year, 2018, marks 800 years since the death of St Robert of Knaresborough. Hazel Blair blogs about her latest trip to the town the hermit made his home, where she delivered a public talk as part of a year-long programme of commemorative celebrations.

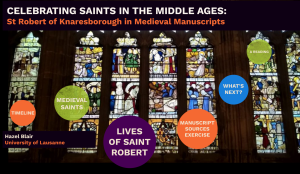

I delivered a talk about stories – medieval stories about saints, and about St Robert of Knaresborough, in particular. Hoping to draw in and engage a wide range of people, my combined presentation and workshop assumed no prior knowledge of the history of the medieval period.

Most medievalists won’t have heard of him, but St Robert is a local celebrity. My aim was to get the Knaresborough-based audience to engage with the historical source materials relating to Robert’s life. I wanted them to see Robert not just as a hermit-saint and long-ago figure, but also as the central character in several interesting and entertaining medieval narratives. I titled my talk (part of St Robert in His Time, organised by Peter Lacey) ‘Celebrating Saints in the Middle Ages: St Robert of Knaresborough in Medieval Manuscripts’.

Everyone introduced themselves briefly before things kicked off, and among the 30-or-so attendees were members of the local historical society, amateur historians, a dentist, a number of self-declared ‘Knaresborough residents’ – and even a couple of academics. This made for a good mix of questions at the end of the day, but it also made for interesting discussions during the group-work phase of the session, with people coming from all walks of life to approach the source materials relating to St Robert in their own individual ways.

Seeing that this was Knaresborough, and seeing that Robert is a well-known local historical figure, I began by asking the audience to shout out any facts they already knew about their local holy hermit, writing their answers up on a flip-chart. This was both to warm up the room and to get some of the main facts about Robert out there in the open, but it was also for me to gauge which aspects of Robert’s sanctity are considered most prominent in Knaresborough today.

I think this opening tactic also quickly established that the voices of the non-historians in the room were just as important as those with more particular knowledge of Robert and his historical context, and I was glad to see some of the ‘Knaresborough residents’ getting involved immediately to help paint a working picture of St Robert for us to refer back to over the course of the afternoon.

Flower of York

Together, we established that Robert Flower was as a holy man born in York who moved to Knaresborough to live in a cave and show devotion to God through prayer and by living chastely. His care for the poor and miraculous abilities over animals were mentioned, and I expanded on this to highlight that he also performed healing miracles and had the ability to vanquish demons.

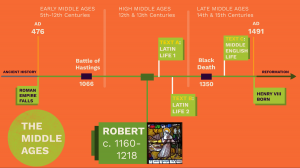

Working picture established, I then moved on to provide a lightning history of the Middle Ages, from the fall of Rome to the reign of Henry VIII, pointing out that Robert lived during ‘the High Middle Ages’, between c. 1160 and 1218. While for several attendees this would not necessarily have been new information, I thought it was important to historically orientate the room – there’s no point in getting interested non-medievalists over the threshold only to alienate them early doors!

Of course, it’s not easy for anyone to absorb lots of information on a new topic in a short space of time, and no-one can be expected to learn ‘the Middle Ages’ in less than a minute (!), but I hope the timeline on my handout and the historical groundwork I laid at the beginning of the talk did its job by bringing into the fold those non-historians whose interest we had piqued when marketing the event. I think visualising time in relation to your subject, either with an on-screen timeline, or – preferably – on a handout, is a sure-fire way to ensure everyone in your audience is on an even footing.

Saints and saints’ stories

Doing my best to avoid the word ‘hagiography’, I then went on to talk more specifically about medieval saints. To anchor the topic, I read (a slight abridgement of) this paragraph from Robert Bartlett’s Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? (Princeton, 2013) – an inexpensive and authoritative book that’s packed full of information yet very accessible:

Of all religions, Christianity is the one most concerned with dead bodies. Many religions have the idea of a holy man or woman – a living human being with extraordinary powers derived from special contact with the divine. Medieval Christianity developed to an extreme degree a distinctive form of this concept: the idea that the dead bodies of these holy people should be cherished as enduring sources of supernatural power. There were thousands of shrines in medieval Europe, containing the dust, bones, and undecayed bodies of the holy dead. Men and women came to these places, revered those whose mortal remains lay there, asked them for favours, and, were cured of their ills. The ecclesiastics who guarded these shrines wrote of the lives of those whose bodies they tended, recorded the wonders they performed after death, and gave the solemn liturgical commemoration in the churches that often bore their names. These were the saints.

I introduced St Polycarp, an early martyr, using dramatic re-imagined images of his persecution at the hands of Roman soldiers in the second century AD. I then moved on to introduce St Anthony, an early ascetic whose way of life mirrored the tortures that Polycarp, and Christ, felt in death. And I discussed the circulation of these early saints’ stories, as well as that of Northumbrian saint St Cuthbert, noting the similarities between the lifestyles of these early figures and Robert’s own way of living in holy discomfort and away from society.

I then gave a short introduction to the manuscripts in which these saints’ stories have come down to us, using this as an opportunity to showcase some of the most impressive manuscripts from the Middle Ages. At every stage, though, I tried to link back to St Robert and to Knaresborough. So after showing some flashy bestiaries and medical texts, I inserted an image from an illustrated life of St Thomas Becket. Picking the scene in which he is martyred, I rounded things back to Knaresborough again, noting that the four murdering knights pictured on screen were said to have fled to the Knaresborough Castle after killing the archbishop.

The many lives of St Robert

Keeping focused on saints’ stories, the hagiographies rather than the individuals on whom they were based, I then introduced three hagiographic texts about St Robert from the middle ages that survive in medieval manuscripts. I emphasised that these were reports, and that while they were well-researched, they were written after the saint’s death by individuals who had not met Robert personally.

Each of the three medieval narratives I introduced told the story of Robert’s life. My aim was to have the audience appreciate that, despite key similarities between the different versions of Robert’s life story as it has survived in medieval manuscripts, each text was authored by a different hagiographer writing in his own historical context with his own preoccupations and priorities.

I wanted the audience to notice the differences for themselves, and to acknowledge that while hagiographies may provide us with a degree of historical access to Robert, they also act as filters and obscure him to some extent, showing us Robert only as the hagiographers chose to depict him. The silver lining, of course, from a historical perspective, is that these same texts can function as windows on to the medieval periods in which they were produced, offering up information about those who remained devoted to Robert long after his death in 1218.

I also wanted the audience to come to see these texts not as obscure medieval texts in dusty old books, but as the beautiful, creative literary responses to Robert’s sanctity that they are – testament not only to his holiness, but also to his ability to inspire Christian devotion and literary expression in those less perfect than himself. So we spent the middle part of the session reading (roughly) translated excerpts from three versions of Robert’s life. I split the room into three groups, A, B, and C, and assigned each group a bundle of individually cut-out excerpts from one of the following texts:

-

- Text A was the Vita Sancti Roberti Heremiti, likely composed in the 13th century and thought to be the earliest extant source for Robert’s life. As Tom Licence has discussed, this text is probably Cistercian and may well hail from Fountains Abbey. I excerpted those parts of the text that emphasised Robert’s asceticism and his retreat to ‘an area of horror and vast solitude’. Seeing that the manuscript of this text is partially destroyed, I provided some supplementary Cistercian texts that used the ‘in loco horroris…‘ phrase, hoping Group A would spot the connection.

-

- Text B was the Trinitarian Latin life of Robert, the Vita Sancti Roberti iuxta Knaresburgum, also composed in the 13th century. This text, as Joshua Easterling has emphasised, was critical in successfully establishing Robert as patron saint of Knaresborough Priory. I picked those parts of the narrative that emphasised Robert’s devotion to the Trinity, and those parts where the hagiographer referred to him as ‘our patron’.

-

- Text C was the Middle English verse life of St Robert, written in rhyming couplets. I spoke about how this text relates to the romance genre at the 2018 Medieval Insular Romance Conference in Cardiff, so I excerpted those portions of the narrative that reflected this best. I picked sections that showed Robert being favourably compared with the likes of Arthur and figuratively constructed as a chivalrous knight.

Making history tangible

Each set of excerpts was wrapped in an image of a page from the manuscript in which the original text survives. I did this so that participants could look at and feel closer to the actual medieval manuscripts containing Robert’s legend, but also to encourage them to further register the clear differences between the three narratives. The way in which the texts are laid out on the page betray these differences: texts A and B are written in continuous lines of Latin prose, but text C stands out visually since it is written in single columns as rhyming verse, each couplet delicately joined with ribbons of red ink.

I let the groups discuss the excerpts they had been assigned (my thanks to Laura Slater, Lindy Grant, and Ruth Salter for checking in on the groups as their discussions progressed!), before asking them to feed back to the room about what had struck them most . I asked them who they thought the author may have been, and about the language used to describe Robert’s life and saintly personality.

We noted down key points from each text, and I wrote these up on a flip chart divided into three sections so we could compare each text’s main features. Everyone was very enthusiastic, and I noticed that among those raising their hands to contribute to the discussion were several more ‘Knaresborough residents’ who – going by their introductions, at least – hadn’t previously had all that much formal interaction with medieval history as a discipline.

And people wanted to know why there were these differences between the texts, and they especially wanted to know why one of the texts referred to their beloved hometown of Knaresborough as ‘a place of horror and vast solitude’! Discussing the phrase as a ‘Cistercian slogan’, I was able to drive home that these words was probably used by the hagiographer not just to underscore Robert’s eremitic retreat from the world, but also to imply some spiritual connection between the saint and the Cistercian Order.

It was great to be able to discuss the different literary levels of the texts, not just as repositories for information about St Robert himself, but also as products of their own individual eras and authorial circumstances. Drawing discussions to a close, I quickly recapped on the main features of the texts in their historical contexts, briefly introducing the Cistercian Order, the Trinitarians, and mentioning the popular genre of medieval Romance as a context for understanding the particular poetical construction of the Middle English version of Robert’s story.

More audience interaction and questions

After mentioning that I had plenty more work to do to bring my thesis on the English Trinitarians and their links to Robert’s cult to fruition, I brought the session to a close with a reading of a Middle English Trinitarian prayer-poem dedicated to St Robert that I had (again, roughly) translated into modern English and printed on the reverse of the timeline handout. Most of the audience joined in in what, I suppose, was the first communal reading of this prayer in more than 500 years.

We then moved to the coffee break, which was followed by a second stimulating session of three talks. Ruth Salter presented on posthumous healing miracles in the high medieval period, Laura Slater delivered a talk linked to her article on connections between the Holy Land and St Robert’s cave, and, finally, Lindy Grant finished by talking about St Robert in context, as one of several saintly and charismatic figures attracting attention around the 12th and 13th centuries.

As a group, we then responded to audience questions about canonisation, miraculous healing, and pilgrimage, before a couple of us headed down to visit Robert’s cave site on the northern bank of the River Nidd. There we found some flyers for the event we had just participated in, pinching a couple to take home as souvenirs – academic pilgrims, indeed!

Hazel Blair

FNS Doctoral Researcher

For more about St Robert in His Time visit the 800th anniversary website, where Hazel, Lindy, Laura, and Ruth have written about the talks they delivered on July 14th 2018 at Gracious Street Methodist Church in Knaresborough. Many thanks to Peter Lacey, James Wright, Gracious Street Methodist Church, and others for ensuring smooth running of the event.

Further reading

Bartlett, Robert, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? (Princeton, 2013)

Bottomley, Frank (trans.), St Robert of Knaresborough (Ilkley, 1993)

Bazire, Joyce, The Metrical Life of St Robert of Knaresborough (EETS, 1953)

Easterling, Joshua, ‘A Norbert for England: Holy Trinity and the Invention of Robert of Knaresborough’, Journal of Medieval Monastic Studies, vol. 2, pp. 75-107.

Licence, Tom, Hermits and Recluses in English Society, 950-1200 (Oxford, 2011)