The Treasures of St Cuthbert is a sumptuous display of medieval artefacts not to be missed. After a long period away from the public view, Durham Cathedral is making available again – in a much improved setting – many of the pre-Conquest treasures associated with the medieval cult of St Cuthbert. These treasures include not only the saint’s coffin, but also its many varied contents, augmented at various points between 698 and the early twelfth century.

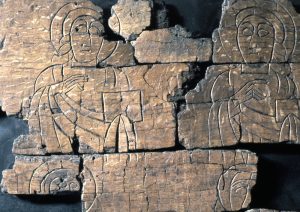

The wooden coffin itself was originally built to contain Cuthbert’s body during the elevation of his relics on Lindisfarne in 698, eleven years after the saint’s death. It is engraved with the twelve apostles on one side (in two tiers), the archangels on the other side, and the Virgin and Child at one end, accompanied by inscriptions in both Roman and runic lettering. Ernst Kitzinger, who reconstructed the fragments of the coffin in the late 1930s, interpreted these engravings as a ‘litany in pictures, invoking the protection of those represented for the relics inside.’

The coffin had a long and eventful history. It was carried around the north of England through the late ninth and tenth centuries by descendents of the Lindisfarne monastery to protect the cult and its precious objects from Viking raids. Twelfth-century historians at Durham, looking back on this peripatetic interlude, supply it with meaning and grandeur by likening it to the exile of the Israelites in the desert carrying the precious Ark of the Covenant.

In line with this perception of the power of the coffin and its contents, it was seen to acquire a kind of agency in its own right. Having survived trips to Whithorn in Galloway, an abortive sea journey to northern Ireland, and a long interim stay in Chester-le-Street, now on the road again it became enormously heavy and impossible to shift on the horseshoe peninsula in the River Wear. This, the medieval Durham historians tell us, is where Cuthbert wished to be laid to rest; this is the spot for a new great church dedicated to his cult – the remarkable early Anglo-Norman structure of Durham Cathedral.

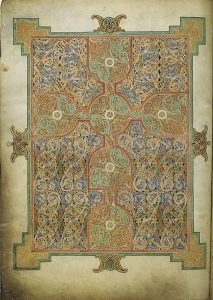

Embedded in the garments close to the saint’s body, and probably placed there in 687 or 698, is a gold and garnet pectoral cross, also on display. An outstanding example of seventh-century Anglo-Saxon jewellery, its design shows close similarities with monastic manuscript illumination, in particular the interwoven decorations that fill the carpet pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Another seventh-century artefact, added to the coffin treasures at some stage, is a small portable altar that may have been used by St Cuthbert as he travelled around Northumbria as a monk or, later, a bishop. Originally a plain wooden oblong, engraved with crosses and an inscription (‘In honour of St Peter’), the altar was later covered with foliated silver plate, and, finally, a central silver roundel, sometime in the eighth or ninth century.

In the tenth century, Cuthbert became an object of interest and veneration for the Wessex royal dynasty. Kings Athelstan and Edmund visited his shrine, then at Chester-le-Street, in the 930s and ’40s, bringing expensive gifts. These gifts included beautiful ecclesiastic vestments: a stole and maniple embroidered with figures of popes and saints, on display in the exhibition, and a famous silk known as the ‘Nature Goddess’ silk, of Byzantine manufacture. This bears traces of Greek inscriptions and seems originally to have arrived in England as a diplomatic gift.

Further sumptuous silks, some possibly from Islamic Spain, were added at the time of the coffin’s opening in 1104, which took place in order to re-verify its contents in front of Anglo-Norman ecclesiastics, before the coffin’s ceremonial re-translation to an elevated shrine in the feretory of the newly-built cathedral at Durham.

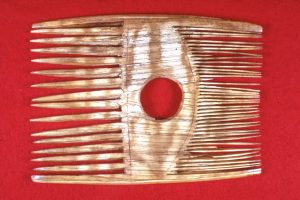

Alongside these beautiful silks and jewels are one or two more intimate items, including St Cuthbert’s comb. Legend has it that this seventh-century, double-toothed comb made from elephant ivory was used by the saint himself to comb his hair before mass after donning his ecclesiastical vestments. One of the singularities of Cuthbert’s cult is that his body is supposed not only to have remained incorrupt, but also flexible, and that his nails, hair, and beard continued to grow within his coffin long after his death.

Reginald of Durham, the twelfth-century hagiographer, described how a devoted eleventh-century sacristan at the shrine used to open the coffin in order to ‘cut the overgrowing hair of [the saint’s] venerable head, to adjust it by dividing it and smoothing it with an ivory comb, and to cut the nails of his fingers.’ The hairs removed from the saint’s head during these grooming sessions had immutable powers in their own right, shining like golden wire and proving inflammable when held within a flame. After he had finished, so Reginald tells us, the sacristan replaced the comb in the coffin.

After 1104, the coffin seems not to have been reopened until 1539, when Henry VIII’s church commissioners arrived at the cathedral to destroy all signs of the saint’s cult. On climbing up to the tomb and opening the coffin, however, it is reported in the Rites of Durham that ‘they found [St Cuthbert] lyinge hole vncorrupt wth his faice baire, and his beard as yt had bene a forth netts growthe, & all his vestm[en]t vpo[n] him as he was accustomed to say mess’.

Apparently impressed, they left the coffin and its contents undisturbed, and it was later reinterred under a stone slab in the feretory beneath the site of the original elevated shrine, not to be opened again until the antiquarian investigations of the nineteenth century.

Christiania Whitehead

FNRS research fellow

The Treasures of St Cuthbert will be on display in the Great Kitchen of Durham Cathedral from 29 July 2017. Visitors to the Treasures exhibit can also enjoy access to the other Open Treasure exhibition spaces, including the Monks’ Dormitory and the rolling programme of exhibitions in the Collections Gallery.

Tickets: £2.50-£7.50, available online or from the visitor desk on the day of your visit. Click here for opening times and further information about Open Treasure.

All images © Chapter of Durham Cathedral, unless otherwise stated.