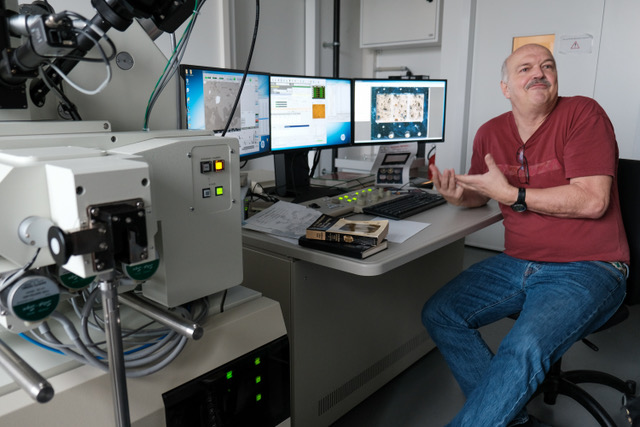

A researcher’s day

How does day-to-day research work? Discover its wonders and challenges: stories of fieldwork adventures, of surprises in the laboratory, thrilling investigations or actions unheard of, that are key to the progress of a research project. Share the doubts and discoveries of the researchers!