Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

This series of conversations brings you the thoughts of our research community on field practice and how it is evolving. See also :

- Conversation with Allison Daley – Fossil stories: testimony to a field in transition

- Conversation with Farid Saleh – Towards a more inclusive and ethical paleontology

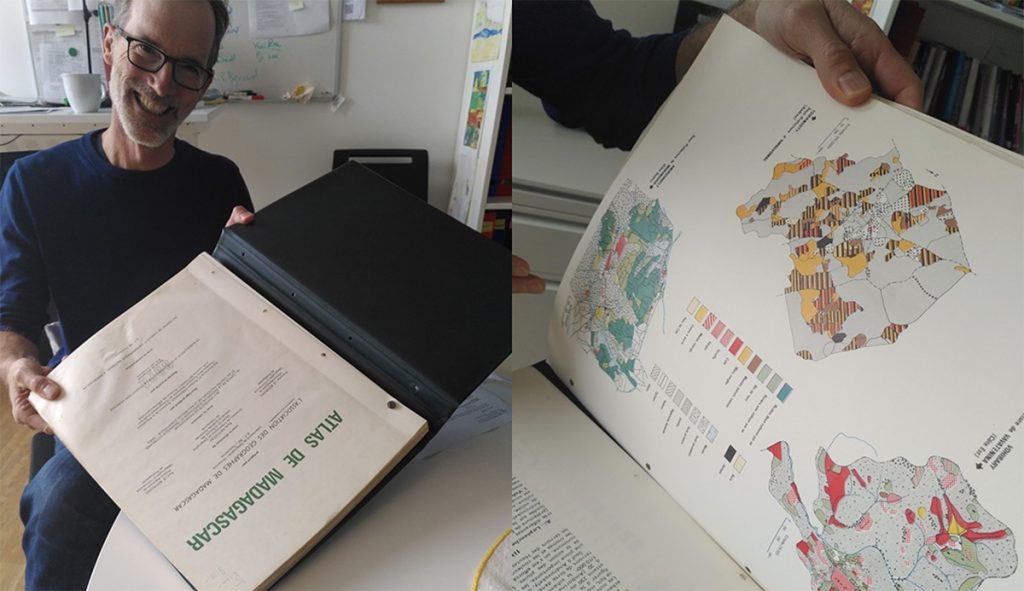

Christian Kull is interested in environmental management in rural landscapes. He has worked in Tanzania, Kenya, India, Vietnam… But it was in Madagascar that he completed his master’s and doctorate. He fell in love with the landscapes of the country’s high plateaus, a mix of forests, terraces and small farms. He tells us how he conducts his ethnographic fieldwork.

Christian Kull is a geographer. His work aims to shed light on the global environmental issues of our time. Environmental management is a central issue affecting human well-being, economic prosperity and sustainability. Rooted in the scientific disciplines of Political Ecology, Development Studies and Environmental Humanities, Christian Kull explores the historical, ideological and political-economic genesis of environmental problems and the conflicts that accompany them. To understand the dynamics of governance and foreign intervention, he has worked in deprived regions of the world.

Christian Kull was president of the CER-GSE when it was launched in 2020, and helped to set it up. In this interview, he talks about his long-term work on wildfires and invasive plants.

What partners do you work with?

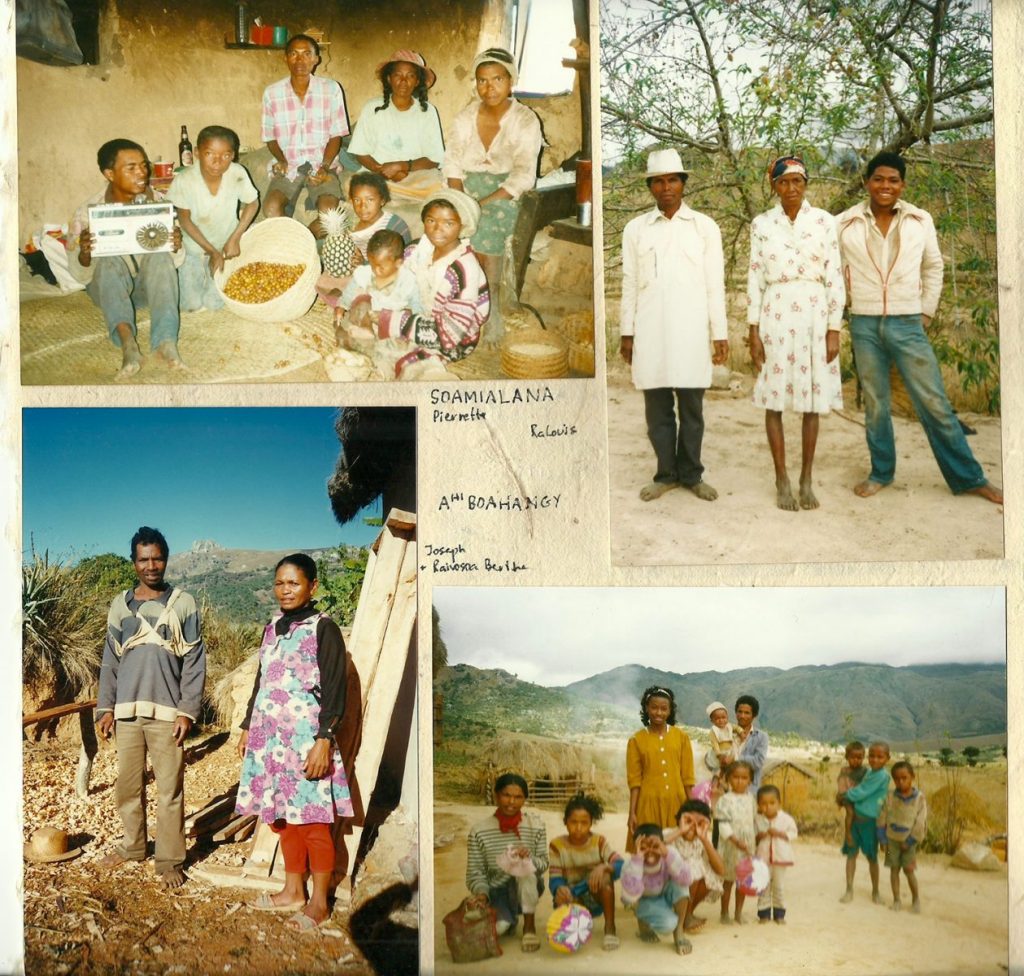

I have a particular interest in local stakeholders. I try to understand how people manage the environment around them, why they plant this or that, cut down trees, burn vegetation… And how these practices interact with national and international policy.

So I work mainly with peasants, but also with people in the rural world – those with administrative positions, the pastor (churches play an important role here), the local school teacher – and on a more global level, with government and NGO officials, people in bilateral aid and at the university.

How did you first come into contact with the people you want to interview?

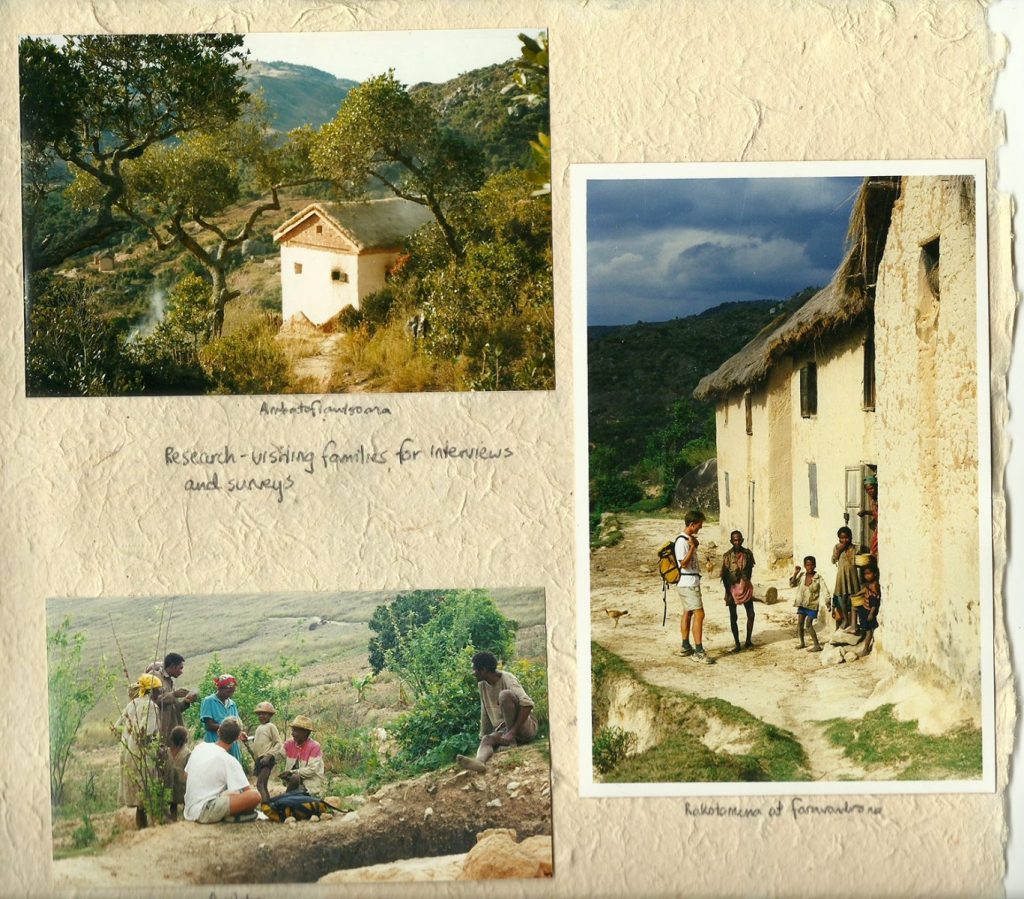

Now, I almost always undertake a project in partnership with the local university, in particular with their school of agronomy, forestry and environment, but also with the geography department. For my Master’s, it was totally different: I bought a plane ticket without knowing whether the professor to whom I had sent a handwritten letter had received it. As soon as I arrived, I knocked on the doors of people at the University of Antananarivo whom I knew only through their articles.

They introduced me to a student, Arsène Rabarison, whom I then hired as a field assistant, as I didn’t speak Malagasy yet. Arsène also helped me in my learning: discovering rural life, knowing how to behave, learning about networks and how to find accommodation, etc.

The peasants are welcoming, and in the hamlets you’ll always find someone to offer food and a place to sleep. The next day, they sometimes send a child to show you the way for a few hours.

Do you need permission to discuss your research questions?

I deal mainly at the local level, with the local town hall. But I also have a letter from the university. For local officials, it’s already a passport if someone in the capital has validated the project.

When I worked at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, I had to follow a more bureaucratic ethical procedure, guided by the challenges of medical research, and aimed at avoiding past abuses towards Aborigines – who suffered from exploitative research. In Madagascar, I always managed to argue for oral consent adapted to local traditions (including formulas for thanking God…). I think the farmers appreciated this effort! For them, signing a piece of paper is rather worrying, and they don’t always read well, so oral consent is preferred.

The ethical form advocated by my thesis university in the USA and by Australian universities was based on the premise that we alone are in a position of domination and power in relation to the locals in these exchanges. Although I have also observed that the figure of the researcher sometimes still commands too much “postcolonial” respect, I am critical of this perspective. I have chosen an oral consent procedure for pragmatic reasons, but also out of conviction. I consider that the people I interview also have a form of power, so I don’t need their signature to formalize our interaction. And I observe it too: if they don’t want to answer, they skirt around the questions with ease, they lie… I trust them! The key point before an interview is to say what I’m doing, that I’m not going to use their name and that they can choose not to answer.

How do you deal with sensitive issues that can get people into trouble?

I’ve worked on fires, which are often illegal. But I never ask directly who started a fire. Instead, I’d say: “Did you see the day before yesterday, there was a fire up there. Why?”. And I’m never told, “I lit the fire for that reason”; but, for example, “I suspect that whoever lit it did so for that reason”.

In my research, I move forward by piecing together observations, by triangulation, building up an argument little by little as if I were conducting an investigation. The Malagasy way of speaking is also rather indirect, so you have to know how to decode!

How do you protect data on illegal practices, such as fire? Do you need to ensure source anonymity?

The issues I’m working on with my partners and team are not highly sensitive, and again, the evidence is indirect since no one says “I started that fire” or “I cleared that forest illegally”.

However, from the outset, the information gathered is separated from the real name of the source. And no file contains both elements, thus preventing cross-checking. If necessary, a correspondence file exists, but separate and password-protected (the name of the file shouldn’t be obvious about the nature of its contents either!).

During my PhD, in my notebook, there were no real names. “Goatee” referred to someone with a small beard. I named a peasant “Ruedi”, who reminded me of my uncle of the same name…

What advice do you have for young researchers before they head out into the field?

I brainstorm with them on interview guides, but the field is really a learning experience. I trust them. You have to dare to try things out, see what works and adjust if necessary.

At Bachelor’s level, students are introduced to qualitative research and learn how to construct a survey. So they have a good grounding, and good manuals too. But it’s all theory … until you’re facing someone you want to interview!

How do you get people to agree to talk about their practices? It’s a social process, where a smile and the way you present yourself are just as important as your knowledge of cultural codes (what’s acceptable, what’s not). Sometimes it’s explaining what you’re doing that’s decisive, sometimes it’s convincing the mayor beforehand. But fortunately, in Madagascar as elsewhere, people like to talk about their lives, as long as someone is interested.

In the Master’s program, we also try to expose students to an “exotic” context. It has to be justified in terms of budget and climate impact, but these are essential learning moments.

Are there any mistakes to be avoided when designing an interview?

A subject close to my heart is that of invasive species. At the beginning, some students ask questions that already contain the answer: “What do you think of these invasive species?” If we ask the question like that, the foresters or farmers will try to please us, and say that these species “invade” them… If we ask them, “What do you think of eucalyptus, their strong and weak points?”, we’ll get other answers. Only then can we go further: “Have you heard that they are invasive? What does that mean to you?” It’s not the same conversation.

How has your relationship with local people developed over time?

For my PhD, I decided to spend four and a half months immersed in the culture and taking intensive Malagasy language courses. Every afternoon, I got on my bike and went to practice basic exchanges with farmers (“Do you grow rice?”). Then I lived in a village for 10 months. Staying in the field for so long allows you to learn a lot about the context in which specific issues are situated. For me, this is invaluable, and it’s the only time in a career when you have the freedom to do this. Little by little, you come to understand the networks, the stories of friendship, family, clan, religion, all those things that are so opaque at first. That’s what our students don’t always have the time to do now.

The ethnographic approach takes time. It’s quite different from the more formalized research interactions that are now being taught more and more.

To go further

Christian Kull is an expert in research on wildfires, a phenomenon that has a major impact on carbon dynamics, biodiversity and ecosystem services. As part of a SNIS project (Swiss Network for International Studies), he is currently exploring the most balanced fire management strategies to meet the needs of local communities and the challenges of climate change. With partners from Swansea University (UK), Antananarivo University (Madagascar), Eduardo Mondlane University (Mozambique), the South African National Parks and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization Madagascar, he is targeting biodiversity hotspots in Madagascar and southern Africa.

He has also contributed to our understanding of invasive species and plants, deforestation and reforestation, protected areas and agricultural conversion.

Discover Christian Kull’s profile, blog and scientific publications.

Leave a Reply