Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

A new Sinergia collaborative project was launched, with Allison Daley, specialist at ISTE of fossils and animal evolution in Cambrien, Marc Robinson-Rechavi and Robert Waterhouse (from the Department of Ecology and Evolution at UNIL) and Ariel Chipman (from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem): “An interdisciplinary study of arthropod moulting”.

How did this project arise? How will a team that brings together specialists in palaeontology, evolutionary genomics, bioinformatics, evolution and development work?

Prof. Allison Daley tells us, and explains what this project means to her.

Let’s find out more about this project.

Arthropods, a global success story

How can we explain the evolutionary success of arthropods? No other animal group on Earth has so many species (6.8 million!) or such a diversity of forms. They are present in virtually all terrestrial environments and in all the ecosystem functions, and this since their origin 500 million years ago!

To understand the evolution of life on Earth, a good starting point is to elucidate what makes this animal group successful. Could the segmented body of arthropods, which gives them ‘modularity’, be the reason for their immense diversification? Their body is protected by a segmented exoskeleton that must be replaced periodically in order to grow.

The project addresses this aspect of arthropod life: moulting. In addition to being a key stage for each arthropod, moulting is one of the only behaviours whose history can be traced back to its origin. It is therefore a fascinating gateway to the evolution of animals. A rare opportunity to follow a complex behaviour over time.

Studying moults in extinct species: mission impossible?

Allison Daley dreams of travelling back in a time machine to look at arthropods of the past – although some of the sea scorpions over 2 metres tall must have been pretty terrifying. But how do you go about it when you’re studying the fossil record?

A modern cicada of the Magicicada genus, in full moult: a striking spectacle. Photo : Dan Keck (licensed under CC0 1.0)

An arthropod moults several times during its life, but it only dies once. If everything is preserved, we would find several moults of increasing size as the animal grows, and a single carcass at the end. In fossil sites where soft tissue is preserved, it’s a no-brainer: if soft internal organs are present, it’s a carcass; if not, you can be sure it’s a moult.

Unfortunately, 99% of fossil sites do not preserve soft tissues. One must then look for evidence that the exoskeleton opened up and the animal came out. But sometimes teams describe fossils that they think are moults according to a list of criteria, considering the context of deposition, while other teams dispute this. This gives rise to much debate!

What do extinct arthropods tell us about the world today?

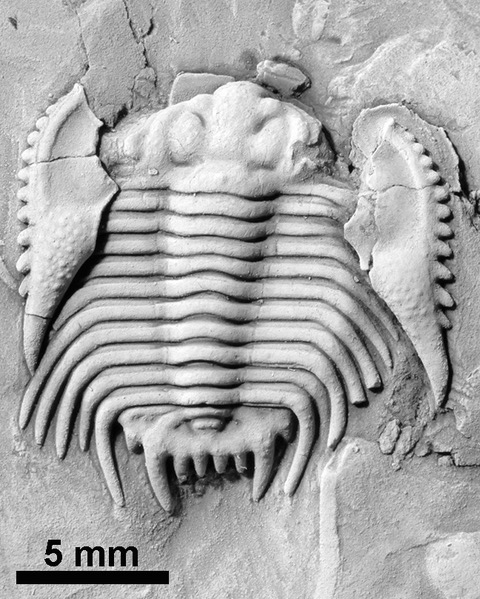

To understand the diversity before us, we need to look into the past. For example, over 300 million years ago, trilobites had an amazing moult: the same species could moult in several different ways, depending on the situation! Today, arthropods have only one mode of moulting. If it fails, the individual dies. There is no backup. Moulting behaviour has become more specific, less flexible. Why did this specialisation arise? What advantages and pressures have driven evolution in this direction? Can we go so far as to say that certain groups – like the trilobites – became extinct because of their moulting behaviour?

Allison Daley and her colleagues hope to answer some of these questions. This project will shed some light on the impressive diversification of modern arthropods, but also on the susceptibility of certain groups to extinction.

Land invasion: different paths to the same goal

Terrestrialisation is a major evolutionary event, the moment when plant and animal life (macroscopic life) conquered dry land. All the major arthropod groups (crustaceans, insects, chelicerates and myriapods) have adapted to terrestrial life at some point. Did this conquest of land occur several times? Was it four times (i.e. once in each lineage)? Or did some lineages switch back and forth between terrestrial and aquatic forms? These are all questions that remain open.

One thing is certain: in order to move from water to the open air, arthropods had to change the way they moulted. But how such a complex behaviour can change so drastically (and probably several times in the history of arthropods!) also remains enigmatic. The interdisciplinary team set up for this project brings together specialists in fossils, but also in genes and their expression, and bioinformatics. This should lead to major advances in the understanding of these upheavals.

Further reading

- ANOM Lab, the website of Allison Daley’s research group

Publications on the topic by Allison Daley:

- The fossil record of ecdysis, and trends in the moulting behaviour of trilobites. Daley A.C., Drage H.B., 2016. Arthropod Structure & Development, 43 pp. 71-96. DOI 10.1016/j.asd.2015.09.004.

- Molecular timetrees reveal a Cambrian colonization of land and a new scenario for ecdysozoan evolution. Rota-Stabelli O., Daley A.C., Pisani D., 2013. Current Biology, 23 pp. 392-398. DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026.

Leave a Reply