Shooting the Emperor: Historical Narratives and Contemporary Imagination

The release in November 2023 of Ridley Scott’s film Napoleon has attracted a considerable degree of attention and generated a flood of controversies in the media. Given the director’s reputation, any new production by him was bound to be widely talked about, and in the past films like Alien and Gladiator were also the object of polemics; however, in this case, it is undoubtedly the subject of the film – the representation of a major historical character – to be the main focus of discussion.

Napoleon on Screen: a Battlefield

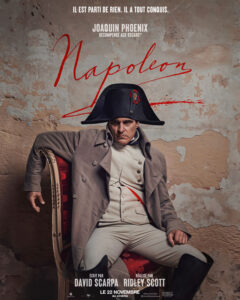

Professional historians, but also reasonably well-informed commentators, have been ready to point out the many features of the film in patent contradiction with the abundant documentary evidence available on the matter. To recall just a few, a recurrent complaint has been over the age of the main interpreter, Joaquin Phoenix. At forty-nine (Napoleon died at fifty-one) the actor is clearly middle-aged, with lined, thick features and a heavy physique; very much unlike the lean, frail, long-haired and nervy young Bonaparte, who was at least twenty years younger than the politicians associated with his career such as Barras, Sieyès and Talleyrand. The Hollywood choice of making the love-affair with Josephine Beauharnais the key to Napoleon’s ambition is also implausibly far-fetched. At first the young officer did fall passionately in love with the older, experienced Josephine. However, far from becoming a life-long obsession as suggested by Scott, his passion faded rather quickly, and soon he was more concerned with his spendthrift wife’s growing debts than with her infidelities.

As it has been pointed out often enough, Napoleon was not present at the execution of Marie-Antoinette in October 1793: he was away from Paris at the siege of Toulon which, incidentally, is also shown in the film. His horror of revolutionary violence was inspired, a year before, by a somewhat different episode: in August 1792 he witnessed, from the premises of a drapery shop nearby, the horrific killing by the mob of hundreds of soldiers of the Swiss guard deployed in defence of the Tuileries palace (a missed opportunity for the director to show a large-scale massacre).[1] Similarly, Napoleon did not take part in the events of Thermidor as he was himself briefly imprisoned at Antibes because of his friendship with Robespierre’s brother Augustin.

Obviously keen on any opportunity for war scenes, Scott shows Bonaparte confronting the royalist insurgents of Vendémiaire (October 1795) with a battery of cannons: an impossible manoeuvre in the narrow Rue Saint Honoré where the fighting occurred. Instead, famously, a “whiff of grapeshot” from the cavalry’s rifles was sufficient to disperse the crowd.[2] Needless to say, the battle of the Pyramids did not involve shooting at the Pyramids themselves, they just provided the background to the fighting. There was no frozen lake at Austerlitz, just icy swamps; on the other hand, a frozen lake features in Sergei Eisenstein’s film Alexander Nevsky (1938), where the heavily armoured Teutonic knights plunge through the breaking ice in one of the most memorable scenes in the history of cinema. Besides, whatever the field, commanders of armies did not charge on horseback or run around shouting orders like Napoleon is shown doing by Scott; aperitifs between emperors after battles were also not current practice. Even before we get on to Waterloo and the (invented) meeting between Napoleon and the Duke of Wellington, the list of historical inaccuracies, not to say blunders, is very long.

Although the script may not be deliberately anti-French as claimed by the French media, it does conform to the traditional English anti-revolutionary propaganda.[3] The Parisian crowds, but also Robespierre and the Convention, are represented as brutal, shouting barbarians; the events of Thermidor and Brumaire, set in non-descript, virtual palaces, are a parody of revolutionary politics, while Napoleon becomes the caricature of himself, a petulant, hapless dictator like Julius Caesar in Asterix cartoons. Understandably, given that battle scenes are what he likes best, Scott ignores altogether Napoleon’s political and administrative activities, missing out on the key to his rise to power, so that the sudden switch to the scene of his coronation comes rather as a surprise.

The director has briskly dismissed all critiques by asking:” Where you there? No? So shut up!” In more polite terms one might argue that after all Scott was not making a historical documentary, but a movie, recreating an emotional and imaginative atmosphere as he saw it. However, the question here is not whether Napoleon is a good or a bad film – in any case the answer is probably unrelated to its historical accuracy. It is rather the choice of subject and the nature of public response: why the disputes about Napoleon, why Napoleon, why now?

“Quel roman que ma vie!”

There are in fact many possible reasons to be interested in Napoleon. To begin with the emperor has an almost secular cinematic career, beginning with Abel Gance’s spectacular (and unsurpassed) epic Napoléon (1927), through Marlon Brando’s romantic impersonation in Désirée (1954), and King Vidor’s War and Peace (1956), to Stanley Kubrick’s ambitious and never realised project of the late 1960s, now apparently to be revived by Steven Spielberg as a serial. He has also featured in countless TV productions in France (by Yves Simoneau in 2002) and abroad.

On a different level Napoleon continues to be the subject of a steady stream of international publications – more books on average than days since his death: these address the different dimensions of his life and works, reflecting the variety of conflicting interpretations of the same. Military strategist, mass murderer, legislator, bureaucrat in chief, conqueror, liberator, gravedigger and/or saviour of the revolution, robber of art works, patron of the arts and sciences, town planner, landscape gardener, romantic writer: there is plenty in his curriculum to choose from. However, what does make Napoleon different from other monarchs with a similarly controversial record and eclectic vocation (like Louis XIV) is the unique trajectory of his rise to power, from military officer from the lesser provincial nobility to ruler of a large part of Europe.

The first to be aware of the exceptional, indeed fantastic unfolding of his destiny was of course Napoleon himself. “Quel roman que ma vie!” he is reported saying in 1816 while in exile at Saint Helena. But the idea of a proximity between historical and fictional narrative was clearly present in his mind long before that. In 1800, after the coup of Brumaire, the First Consul addressed the newly established Conseil d’État with the surprising claim: “We have brought to an end the novel (roman) of the Revolution; it is now time to begin its history”; he then pursued the speech explaining that, in order to govern, one must distinguish what was “real and possible” in revolutionary principles, from what was mere philosophical speculation.[4]

From the beginning of his military career, Napoleon carefully built his own public image as the protagonist of a heroic saga, employing talented artists such as Antoine-Jean Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Andrea Appiani and Antonio Canova to provide memorable visual support to his narrative. To some extent the representations they produced followed conventional patterns: the military commander on horse-back, the legislator surrounded by books and codes, the monarch carrying the symbols of his power, the marble god of Roman inspiration. Yet at the same time they conferred to their subject an aura of youth, audacity and energy that transcended traditional models. The exotic settings of some of his early exploits, like Egypt, gave to his adventures a broad, far-reaching appeal, stretching from classical antiquity to the present, from legend to history, just as he had intended.

From the beginning of his military career, Napoleon carefully built his own public image as the protagonist of a heroic saga, employing talented artists such as Antoine-Jean Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Andrea Appiani and Antonio Canova to provide memorable visual support to his narrative. To some extent the representations they produced followed conventional patterns: the military commander on horse-back, the legislator surrounded by books and codes, the monarch carrying the symbols of his power, the marble god of Roman inspiration. Yet at the same time they conferred to their subject an aura of youth, audacity and energy that transcended traditional models. The exotic settings of some of his early exploits, like Egypt, gave to his adventures a broad, far-reaching appeal, stretching from classical antiquity to the present, from legend to history, just as he had intended.

While his career as romantic novelist was mercifully confined to the publication in 1796 of the novella Clisson et Eugénie, the recollections he dictated while in exile, Emmanuel de Las Cases’ Mémorial de Sainte Hélène (1823), became an immensely popular handbook for the lost dreams of glory of several generations.[5] In her book L’homme qui se prenait pour Napoléon, based on a study of the archives of 19th century French asylums, historian of psychiatry Laure Murat argues that the reason why so many mental patients identified with the French emperor (turning the image of the lunatic wearing Napoleon’s hat into a popular stereotype) was that is some sense anybody could be him: the delusion was accessible, timeless, and universal.[6]

The Historian as Scriptwriter

If what we think we know about Napoleon is to a large extent a skilful fabrication of his own making, why should we complain if today an English director and an American scriptwriter create their own semi-fictional hero in a semi-fictional universe? Throughout the 19th century historians of the Revolution did not hesitate to resort to literary embellishments and inventions, helped in the exercise by the flood of often inaccurate, if not deliberately mendacious recollections left by the survivors on all political sides.

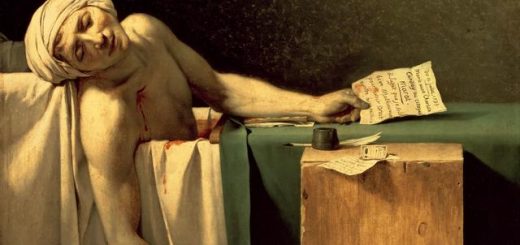

Thus, in his popular Histoire des Girondins (1847), written with the explicit intention of making money (it did), Alphonse de Lamartine delighted his readers by inventing tearful scenes, dramatic effects, and extraordinary coincidences with little regard for historical truth. Accordingly, he had Mme Roland imprisoned in the same cell that had been occupied by Marie-Antoinette, sent Charlotte Corday to the scaffold dressed in a red shirt, attributed the success of the coup of Thermidor to a sentimental disappointment suffered by Saint-Just, and described the Seine continuously flowing with blood. Even a more committed historian like Jules Michelet in his major work Histoire de la révolution française (1847) could not resist the temptation of attributing to his protagonists dialogues and emotional reactions for which he had no evidence, but that he deemed appropriate to their circumstances.[7]

As time went by, however, because of the emergence of new, more “scientific” and theoretically structured approaches to the study of the Revolution, historians have abandoned the speculative accounts of the conduct of major individual actors, focusing instead on broad collective phenomena such as economic conditions, political ideologies, and class conflicts. Biographical studies continued of course to be produced, but professionally they were seen as complements to the larger perspective. In any case the distinction between serious academic history, based on theoretical models, objective circumstances, and measurable data on the one hand, and fictional narratives on the other, seemed firmly established.

Yet over the last few decades this apparently solid frontier between professional history and fictional narratives has begun to crumble. A major factor in this process has been the growing attention attributed in historical research to the experience of “ordinary” individuals: if history is made by the people, then one should know more about them than what is provided by demography or statistics. What was it really like at a given time to be a peasant, an artisan, or a soldier? Who built the cathedrals, who were the anonymous victims of the Inquisition and the people accused of witchcraft, who manned the barricades? This approach has proved especially relevant to the development of the history of women. Because women were generally excluded from public roles, it was necessary to study their predicament by looking at individual cases, private recollections, unofficial testimonials.

Clearly the historians who pursued these lines of research based their studies on surviving records and documents, they did not make them up. But this type of “microhistory” required greater imaginative involvement than conventional social history: it was the feeling of personal identification that made books like Carlo Ginzburg’s seminal Il formaggio e i vermi – based on the trial of an obscure 16th century heretic – so widely popular.[8] Inevitably these types of narratives have come closer to those produced by the writers of historical fiction: a genre that in recent years has known an extraordinary development, stretching beyond the usual romanticised vicissitudes of kings and queens to describe the predicament of anonymous people, or of less known historical characters.

Indeed, in some cases successful fictional reconstructions have taken the lead, forcing academic historians to reconsider their assumptions. Possibly the most striking recent example of this reversal of roles has been the publication of Hilary Mantel’s novels Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring up the Bodies (2012), based on the career of Henry VIII’s influential, but little known minister Thomas Cromwell. Widely translated and transposed into stage and TV adaptations, the novels turned the confidential advisor and promoter behind the scenes of the English Reformation into a popular figure. As a result, Cromwell, until then side-lined by academic historiography, has since become the object of several new studies reappraising his contribution.[9]

Unlike Hilary Mantel’s novels, Scott’s film is not likely to have any impact on current scholarship. The emperor is doing very well under his own steam: about ten new titles in English and French in 2023, not counting reprints. Thus far its only noticeable effect is on marketing: bookshops have placed available works on Napoleon on display in prominent positions, and probably some biographies or illustrated collections of battles (never out of print!) featured on the readers’ Christmas lists. In November 2023, as the polemic around the film was just taking off, one of Napoleon’s bicorn hats sold at auction in Paris for over two million dollars.

Meanwhile the controversies over the film have turned into a kind of imperial reality show. John Hollingworth, the English actor interpreting the role of Marshal Ney, has expressed concern over his make up: Ney was known as le rougeot for his flaming red hair, while in the film he is sporting big black moustaches. This capillary issue has become the occasion for heartfelt exchanges between the actor and some descendant of the incorrectly hair-styled Marshal. Other distant members of the affinity around the Bonaparte family have released interviews to the press formulating confused opinions about the portraying of their ancestors. More soberly Charles Bonaparte – direct descendant of the emperor and former socialist mayor of Ajaccio – at a meeting of the Federation of Napoleonic Cities he founded in 2004, has expressed mitigated appreciation for the film, while reasserting his own strong republican sentiments.[10] No doubt the subject will soon fade from the media, and the disputes over Napoleon will be once again confined to historians and to the millions of his dedicated admirers around the world (Harry Potter’s fans being probably the only comparable constituency in terms of numbers). The question we are left with is not what the film says about Napoleon, but rather what it says about us.

Forgetting Waterloo

All considered, and regardless of Scott’s own intentions, two themes stand out: the myth of charismatic leadership and the reappearance of war in the heart of Europe. Russia’s ongoing aggression against Ukraine has generated in European observers a feeling of disorientation and helplessness: as the established balance of powers crumbles, Europe’s place within it is also called into question. For the first time since 1945, war is no longer a distant reality, unfolding in remote jungles and deserts; it is no longer cold, but it is hotly deployed along Europe’s frontiers, just as it was once on the fields of Valmy, Marengo or Waterloo. Accordingly, the question of national defence and rearmament (for Switzerland of neutrality) is back on the agenda of European democracies.

After seventy years of nearly peaceful rule by faceless institutions, there is a feeling of dissatisfaction towards the prudent balancing act of democratic governments. Accordingly, the focus of attention is turned back towards those leaders of the 20th century who seemed to provide firm, clear guidance, especially in confronting military aggression. To mention a few recent examples, in 2022 the late Henry Kissinger published Leadership, Six Studies in World Strategy, while Ian Kershaw (Hitler’s authoritative biographer) has taken Max Weber’s notion of charismatic leadership as a basis for his Personality and Power, Builders and Destroyers of Modern Europe. Churchill and De Gaulle in particular have become the object of several studies in this perspective, from Patrice Gueniffey’s Napoléon et De Gaulle, deux héros français (2017) to Ian Buruma’s The Churchill Complex (2020) and David Reynolds’ Mirrors of Greatness, Churchill and the Leaders who Shaped him (2023).

While this return of the great man (or woman[11]) in collective imagination may betray a secret craving for reassuring authority, the fact remains that strong leadership and democracy are not easily reconciled. Whatever the admiration we might feel for one or other great historical personalities, the nostalgia displayed by the recent revivals of past national glories is bound to be half-hearted. The choice to trace Napoleon’s progress from revolutionary liberator to conquering despot is revealing of this ambivalence, of the uneasy combination of admiration and alarm in the face of outstanding individual abilities and ambitions. After all democratic freedom rests on the principle of being ruled by laws and institutions, not by anyone’s will.

A similar ambiguity is apparent in the representation of war. Scott’s Napoleonic battles are as spectacular and grandiose as they are remote from reality. Immense armies advance smoothly in straight lines or ride along in smoky clouds across lunar landscapes as in a gigantic videogame. Only the occasional spot of colour of flags and uniforms suggests that we are not watching The Lord of the Rings, the Clash of the Titans, or some other legendary epics. Phoenix-Napoleon covers his ears every time the guns fire, but the shots crackle and sizzle like fireworks.[12] One needs to look at Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lindon (1975) – where the director “recycled” one battle scene he had originally planned for his film on Napoleon – to get a sense of what it must have been like for foot soldiers to face artillery fire in some 18th century conflict.

It is difficult to believe that Scott’s computer-generated battlefields belong to the same universe as the bleak landscapes and the outdated, ungainly 1960s Leopard and 1980s Abrams tanks we see on TV, crawling along the muddy roads of Ukraine. What Scott’s Hollywood fantasy is mirroring back to us is our incapacity to face a dismal, confusing reality without being side-tracked by obscure delusions and fears.

It is difficult to believe that Scott’s computer-generated battlefields belong to the same universe as the bleak landscapes and the outdated, ungainly 1960s Leopard and 1980s Abrams tanks we see on TV, crawling along the muddy roads of Ukraine. What Scott’s Hollywood fantasy is mirroring back to us is our incapacity to face a dismal, confusing reality without being side-tracked by obscure delusions and fears.

When in 2007 the Eurostar terminal in London was moved from Waterloo Station to St. Pancras, the change was advertised by large posters showing Napoleon at the head of his army with the notice: “Forget Waterloo!”. In those happy pre-Brexit times, the catchphrase was meant as a friendly encouragement to further Anglo-French rail travels. Admittedly for the last two centuries forgetting Waterloo has proved rather difficult. But with Scott we have been watching the wrong movie. These days the mythical commander with the bicorn hat and the binocular can be safely left to his own legend. It is the pragmatic politician who wished to rescue what was “real and possible” in the revolutionary agenda; who recognised Europe’s political and military fragility, and yet believed in the possibility of a federation of free states; who advocated pan-European laws and institutions and a single European currency: that less known Napoleon may still be worth watching.[13]

Biancamaria Fontana is Emeritus professor of History of political thought at the University of Lausanne, and a member of the Walras Pareto Centre for the history of economic and political thought. Her last book is on La République helvétique, laboratoire de la Suisse moderne.

Footnotes

- Alain-Jacques Tornare, 10 août 1792, Les Tuileries : l’été tragique des relations franco-suisses, Lausanne, Savoir Suisse, 2012. ↩

- Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution, a History (1837), ed. John Rosenberg, New York, Random House, 2002, p. 320. The ‘whiff’ did manage to kill between one and two hundred insurgents: the Convention had suggested using blanks, but Bonaparte argued real bullets were ‘safer’. ↩

- See for example the views of Bonaparte’s biographer Patrice Gueniffey, “Napoléon c’est le film d’un anglais très anti-français”, Le Point, 14 Nov. 2023; but see also Ruth Scurr, “How the English invented the Myth of Napoleon”, The Telegraph, 22 Nov. 2023. ↩

- Quoted in François Furet, « Napoléon Bonaparte (1799-1814) » in La Révolution française, Paris, Gallimard, 2007, p. 456. ↩

- Napoléon Bonaparte, Clisson et Eugénie, Paris, Fayard, 2007; Le Mémorial de Sainte Hélène par le Comte de Las Cases, ed. André Maurois, 2 vols, Collection Pléiade, Paris, Gallimard, 1948; Napoléon à Sainte Hélène, ed. Jean Tulard, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1981; see in particular Napoleon’s own perceptive comments on the difficulty of establishing historical truth, pp. 428-430. ↩

- Laure Murat, L’homme qui se prenait pour Napoléon, Paris, Gallimard, 2011 (The Man who thought he was Napoleon, London, University of Chicago Press, 2014). A professor at UCLA and committed LGBT militant, Laure Murat is a descendant of Napoleon’s sister Caroline and of the King of Naples Joachim Murat. ↩

- Alphonse de Lamartine, Histoire des Girondins, ed. Mona Ozouf, 2 vols, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2017; Jules Michelet, Histoire de la Révolution française, ed. Paule Petitier and Michel Biard, 2 vols, Collection Pléiade, Paris, Gallimard, 2019. ↩

- Carlo Ginzburg, Il formaggio e i vermi, Torino, Einaudi, 1976 (The Cheese and the Worms, The Cosmos of a Sixteenth Century Miller, Baltimore, John Hopkins Press, 2014). ↩

- The most widely documented being: Diarmaid MacCulloch, Thomas Cromwell, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 2018. ↩

- The federation deals with the preservation of the artistic patrimony associated with Napoleon across Europe; for Charles Bonaparte’s political views and family recollections see: Charles Bonaparte, La Liberté Bonaparte, Paris, Grasset, 2021. ↩

- Margaret Thatcher is the only woman-leader to feature in these works. ↩

- Scott had done much better in representing war in Black Hawk Down (2001): clearly history is not his forte. ↩

- Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe, London, Routledge, 1991; Paul W. Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848, Oxford, Clarendon, 1994; Biancamaria Fontana, « The Napoleonic Empire and the Europe of Nations », in Anthony Pagden ed. The Idea of Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 116-128; Benedikt Koehler, « From Napoleon to the European Union », The Article, 25 April 2021. ↩

To cite this blog post : Biancamaria Fontana, « Shooting the Emperor: Historical Narratives and Contemporary Imagination », Blog of the Centre Walras Pareto, January 22, 2024, https://wp.unil.ch/cwp-blog/2024/01/shooting-the-emperor/.