Guest-blogger Christiane Kroebel, who is an independent researcher and volunteer curator at Whitby Museum, reflects on the origins and development of St Hilda’s cult from the middle ages to the present day.

The 1338th anniversary of St Hilda’s death, or the date of her birth in heaven, is coming up shortly on 17 November. The life of this English woman who stood up to pressure from Wilfrid to conform to Roman practices, specifically the dating of Easter and the tonsure, continues to generate a sense of pride in the present-day north. To try to understand why there is this perception of a Celtic versus Roman divide, I started a search for the saint from the twenty-first century back to the Middle Ages and for Hilda as a person from the seventh century forward.

A woman of strong character

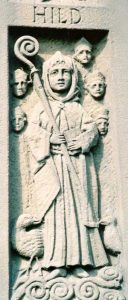

The person who emerges from the pages of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People is of a woman of strong character and principles. Although she was portrayed by Bede and Wilfrid’s biographer, Eddius Stephanus, as opposing the Roman dating of Easter and tonsure (correct in their view), and standing with the Irish clergy against the Romans, it should be remembered that Hilda had been baptised by Paulinus, the monk from Rome sent by Pope Gregory in 601. Paulinus also instructed her in Christian practices until she was probably 19 years old, i.e. until 633, when he returned to Kent after King Edwin’s death.

Hilda, a great-niece of Edwin, re-emerges in Bede’s narrative at the age of 33, when Aidan persuaded her to leave the South of England and return home to found a small monastery on the north side of the River Wear. The following year, she became abbess of the double monastery at Hartlepool, and eight years later, in 657, she founded the double monastery at Streanæshealh (Whitby).

It was usual in the seventh century, for women from royal families to head double houses (foundations for both nuns and monks). At Whitby, Hilda established the same rule as at Hartlepool and the Wear, teaching the virtues of justice, devotion, chastity, and the necessity of living in peace and charity. There was to be no private property: everything was held in common. In Bede’s words, ‘so great was her prudence that not only ordinary people but also kings and princes sometimes sought and received her counsel when in difficulties’ (HE iv.23).

Hilda is likely to have founded a minimum of two schools at Whitby. One was for those wishing to study scripture; here many became priests, and six were promoted to bishoprics. The other was for novices who were educated in a remote part of the monastery. She died in 680 at the age of 66, after 23 years at Whitby, and was succeeded by another abbess from the Northumbrian royal family, Aelfflæd. It is to Aelfflæd and her mother Eanflæd, Edwin’s daughter and King Oswiu’s wife, that we should look to for the first commemorations and then memorialisation of Hilda’s life.

Northumbria’s ‘golden age’

Aelfflæd’s tenure at Whitby, until 714, coincided with Northumbria’s golden age, the time of the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Codex Amiatinus, the various Lives of Cuthbert, Wilfrid, and Pope Gregory, and Bede’s earliest works on scripture. No Life of Hilda has survived but there are indications in the ninth-century Old English Martyrology that one existed then.

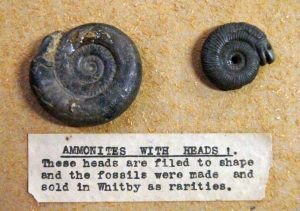

Fast-forward to 2015 when I started my search for the origin of the myths associated with St Hilda: the story in which she forces the snakes at Whitby over the cliff and turns them to stone so that they become ammonites, and the story in which she banishes geese from flying over the abbey because they have eaten all the community’s corn.

These two stories are repeated in all the popular books about Hilda but without any attribution to original sources. Three years later, I know that Hilda’s myths were included in Richard Pynson’s 1516 printing of The Kalendre of the Newe Legende of Englande in Middle English, and in Wynken de Worde’s Nova Legenda Anglie, a 1516 edition of John of Tynemouth’s fourteenth-century Sanctilogium. A fifteenth-century Latin manuscript in Durham University library additionally takes the ammonite tale back into the late medieval period.[1]

A nineteenth-century revival

Along the way, I got side-tracked by the nineteenth-century revival of church dedications to St Hilda, mostly in the North and appropriately, the dedication of two colleges to her: one in Oxford for women students, the other a women’s teacher-training college in Durham. It was not easy to find an answer to why there was renewed interest in Hilda at this time, but the medieval period and especially the early medieval seemed to have been coloured with a romantic hue in the public imagination.

For historians, this became a search for the values of people in the past, which took me straight back to the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century antiquarians and their Italian humanist inheritance. There is no doubt that we owe these English antiquarians a huge debt for collecting and saving the medieval documentary heritage, which enables us to research and discuss people like St Hilda, and those who became interested in her after her death.

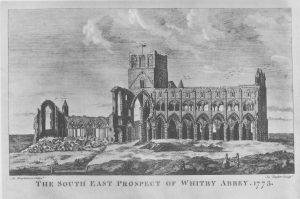

Back in the medieval period, my search took me to look for churches with medieval dedications as well as references to Hilda in church calendars and liturgies. The story of why a former soldier in William the Conqueror’s army (the Evesham monk Reinfrid) wanted to re-found a monastery in Whitby is so well-known that it does not need repeating, but some credit should be given to the Abbot of Evesham for supporting Reinfrid’s quest.

The story highlights that southern English monasteries knew their history, probably from the pages of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, and valued their past. Credit is due also to William Percy, who gave Reinfrid some land on the site of Hilda’s monastery. Reinfrid was a hermit at heart, but his devotion attracted a following and, by the end of the eleventh century, after Reinfrid’s death, the Percy family asserted their interests and William Percy’s brother Serlo became prior, followed by a nephew, who became abbot in the first decade of the twelfth century.

Mysterious origins

The question of whether church dedications reflect the post-Conquest revival of interest in St Hilda or had their origins in the Anglo-Saxon period cannot be answered with certainty. The archaeology can tell us much about the early origins of church buildings, but dedications in the documentary evidence are late. References in calendars and liturgies are also late, mostly dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Whether this is a reflection of the survival of sources or of the spread of the cult is difficult to know.

When the two myths came to be added to St Hilda’s life is a mystery; although both are appropriate, neither is unique to Hilda. It is easy to imagine the ammonites as fossilised snakes, while nearby Scaling Dam is a greylag and Canada geese winter breeding site today – and it’s true that they don’t seem to fly over Whitby to get there!

Christiane Kroebel

Independent researcher and Whitby Museum volunteer curator for the Abbey collection

[1] A. I. Doyle, ‘A Miracle of St Hilda in a Migrating Manuscript’, in Crossing Boundaries, ed. by Eric Cambridge and Jane Hawkes (Oxford: Oxbow, 2017), pp. 243-47.