On the 800th anniversary of his death, Hazel Blair discusses some key manuscript sources for St Robert’s life and cult, all of which are held in the British Library in London.

St Robert of Knaresborough was a medieval hermit from Yorkshire, famed for his asceticism, miracles, and inexhaustible care the poor. His name is less well known today, although his tiny cave-chapel in Knaresborough remains a popular tourist attraction. Complementing the archaeological and artistic evidence for his life and cult, however, there is a wealth of literary material relating to the saint among the treasures of the British Library manuscripts collection.

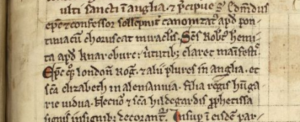

The Lanercost Chronicle (BL Cotton MS Claudius D VII) says Robert died on the 24th of September 1218, and – according to chronicler Matthew Paris (Historia Anglorum, BL Royal MS 14 C VII) – he worked tomb-based miracles of such renown that he was counted alongside the likes of St Hildegard of Bingen as one of the most noteworthy saints of the first half of the 13th century.

According to his legend, Robert was born in York and showed signs of holiness from a young age. He first tried out life in the church, but this young man’s Christian faith was so strong that he felt he had to strike out on his own – establishing himself as a religious hermit on the outskirts of the old West Riding town of Knaresborough. Robert lived there as an ascetic, abstaining from worldly pleasure and inflicting pain on himself in order to express his devotion to God. He eventually moved into a cave on the northern bank of the River Nidd, to which his brother attached a small private chapel to aid him in his devotions.

Robert gained a reputation for helping poor folk, offering them food and shelter. He was also a noted miracle worker who healed broken bones and exerted supernatural control over the deer who ravaged his crops. He even vanquished a series of demons who were determined to torment him, and his holy reputation was such that he caught the attention of King John, who sought him out and granted him land and alms to be distributed among the needy.

Robert foresaw his own death and warned that Cistercian monks from the nearby abbey of Fountains would try to steal his corpse to inter it in their monastery. He told his followers that these monks should be resisted, and so, when the time came, the Cistercians were met by an armed force of men from Knaresborough Castle. The monks left empty-handed, and Robert was buried in the chapel by his cave, his funeral attended by men and women from all strata of society. As a talented miracle-worker, he effected a wide range of posthumous healings at his tomb: the blind were restored their sight, lepers were cured, and some people were even resurrected.

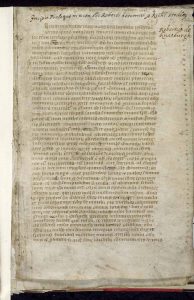

In addition to the fleeting references to Robert that may be found in the chronicles cited above, this hermit’s life story is preserved in much greater detail in BL Harley MS 3775. This late medieval manuscript, likely compiled at the Benedictine abbey of St Albans, contains an earlier Latin prose account of Robert’s life, attributed to someone called Richard Stodley. The text, which may be Cistercian in origin, focuses on Robert’s virtues as an ascetic hermit.

This manuscript links its lives of Robert to two verse histories narrating the foundation of the Order of the Holy Trinity for the Redemption of Captives. The Trinitarians were founded in France in 1198 to ransom Christians held captive during the Crusades, and their network of houses included a priory dedicated to St Robert in Knaresborough, established c. 1252. The Knaresborough Trinitarians managed Robert’s shrine from the mid-13th to 15th centuries, and the combination of literary material in Egerton 3143 suggests the manuscript was compiled at their priory towards the end of the medieval period.

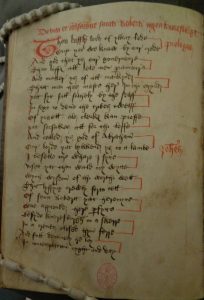

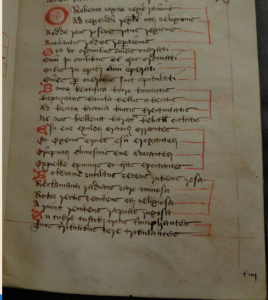

The histories and hagiographies in Egerton 3143 were edited by Joyce Bazire for the Early English Text Society in 1953, but the manuscript also contains a collection of unedited prayers directed towards St Robert that are currently accessible only in manuscript form. This unedited material is explored more fully in my PhD thesis and deserves far more attention than I can give it in a single blog post. So let me finish by highlighting the most eye-catching of these forgotten prayer texts, a Latin prayer with a distinctive alliterative pattern:

Down the left-hand side, you might notice that the first letters of each stanza (almost) spell out ‘Robert’. I say ‘almost’, because although Robert’s name is cryptically embedded within this prayer, it is not your average acrostic. Rather, the first paragraph of the prayer uses lots of R-words, the second lots of O-words, and so on, so that each stanza’s internal alliteration directs attention towards each of the letters in ‘Robert’. In effect, it asks readers and listeners to pause and meditate on Robert’s name and everything holy that it was deemed to represent.

BL Egerton MS 3143, with its intertwined and closely interlinked historical, hagiographic, and liturgical texts in Latin and Middle English, is a rare survival from the medieval period. Not only does it serve as evidence for the medieval cult of St Robert and its development into the later middle ages, but it also offers a unique window onto the history of the English Trinitarians.

Hazel Blair

Doctoral Researcher

The contents and contexts of the manuscripts cited here (and BL Egerton MS 3143, in particular) are the subject of Hazel Blair’s PhD thesis, which is being supervised at the University of Lausanne by Professor Denis Renevey and Professor Christiania Whitehead. The thesis, due for completion in 2020, is titled ‘The Cult of St Robert of Knaresborough and the Trinitarian Order in Medieval England’. It is being funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation as part of the research project ‘Region and Nation in Late Medieval Devotion to Northern English Saints’. Hazel holds an MA (Hons) in Medieval History from the University of St Andrews and an MA in Medieval and Renaissance Studies from University College London. Tweet her at @MediaevalScribe (that’s ‘mediaeval’ with an ‘a’!).