Written by:

- Julie Fahy (University of Applied Sciences and Arts – Western Switzerland / University of Geneva, Switzerland)

- Melissa Hernández-Poveda (Department of Biological Sciences, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia.)

- Caroline Martin (Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, Switzerland)

- Shiloh Narayan (College of Engineering, Science and Technology, Fiji National University, Suva, Fiji)

- Bismark Ofosu-Bamfo (Department of Theoretical and Applied Biology, KNUST, Ghana)

- Jacelyn See Choon Min (Department of Forestry Science and Biodiversity, Universiti Putra Malaysia / Malaysian Nature Society)

Introduction

When we think about conservation, what perhaps comes to mind is mainly large forests, deforestation, and large mammals losing their habitats. However, we do not stop to think about how large this issue is, all the diverse factors and actors involved, as well as the living organisms that may be threatened for different reasons and all the work that goes behind conservation. Interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity are crucial strategies to create better and more efficient projects. Therefore, this course sought to bring together a group of young biologists who were interested in understanding and using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species methodology to assess species extinction risk, as well as species monitoring and ecological niche modelling methodologies, through transdisciplinary work.

This was the perfect opportunity to bring together in Lausanne, Switzerland, 12 biologists from all continents, belonging to different cultures, with different challenges, but united by a shared passion for conservation, working with totally different groups and methodologies, including plants, insects, birds, herps, fieldwork, and/or bioinformatics and even environmental DNA, together with an incredible and equally diverse group of speakers that made this a very enriching space.

That week was a space where we could understand better in some cases, learn from scratch in others and/or complement our knowledge in different topics such as species threats in a global context, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, how to apply it to species data, models and statistics for determining the size of a population, how Red List criteria can be improved/complemented by models and niche analyses, and species monitoring, including developing a species monitoring plan.

The course was originally planned to start more than 2 years ago. However, due to the pandemic, these plans were cancelled because UNIL wanted the course to be in person so that we could get as much time to learn as possible, to be able to attend the class in person, and create a good ‘breeding ground’ for networking, sharing ideas, and meaningful connection.

Why? Because this course was not just about listening to experts on the subject, it was also about learning and teaching by everyone, which made it even more enriching. For this reason, some of us who had applied for the 2020 course had decided to wait all this time to finally make it happen this year and it was worth the wait.

Nature Conservation

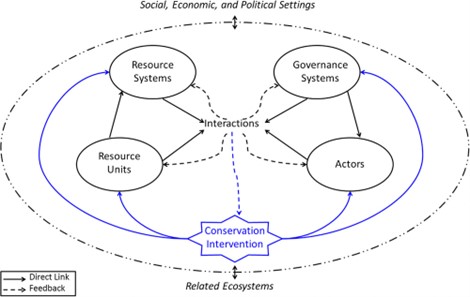

The first day of the summer school started with an introduction to nature conservation by Prof. Gretchen Walters from UNIL. It was interesting to learn about the history of conservation as we know and see it today: earlier in conservation history, humans were seen as bad for nature and thus, often entirely excluded from protected areas. Also, protected areas in many countries were created in the colonial era, thus creating or perpetuating inequalities. Many current conservation efforts recognize that people and nature can co-exist and also recognize the various actors in conservation. But conservation experts, who are often biologists, do not always have the capacity to involve all stakeholders or value the knowledge and contribution of local people, thus creating a need for a transdisciplinary approach to conservation involving ecologists, environmentalists, politicians, and social scientists. We were also introduced to seeing species threats or conservation actions within the context of a social-ecological system. Using a social-ecological system provides a bird’s eye view that helps to identify the resource that needs to be conserved, the system within which that resource occurs, and the users and the governance system within which the resource is regulated. It provides an opportunity to determine where conservation interventions should be directed and where feedback should be expected from.

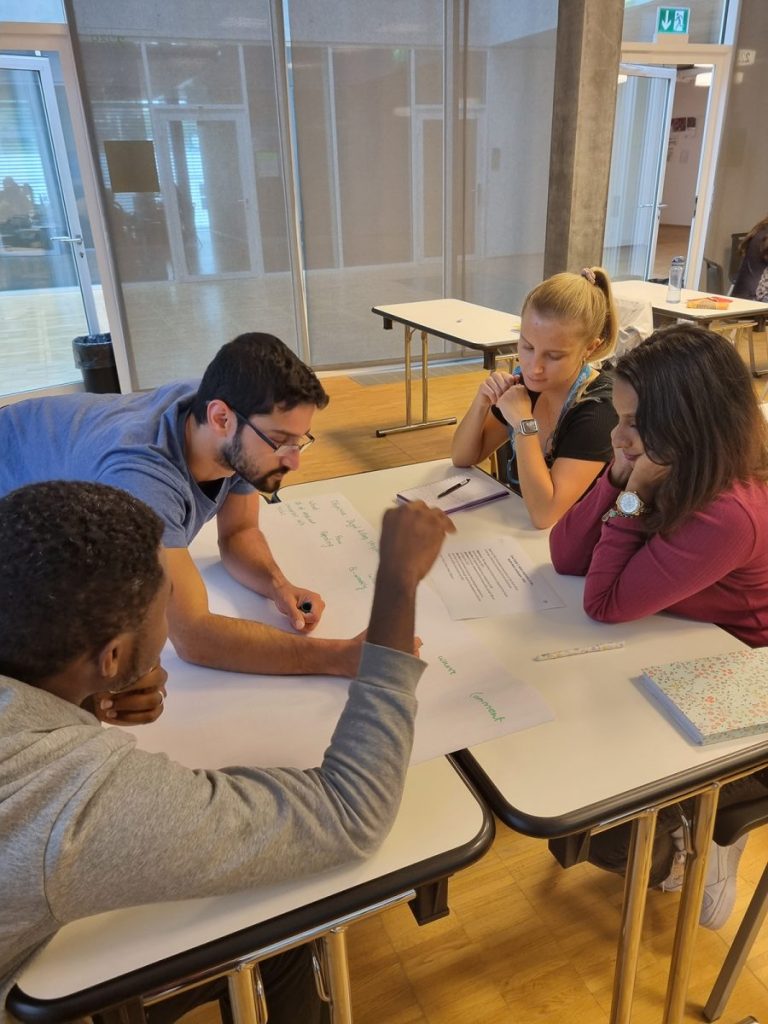

One of the activities we completed on social-ecological systems was to apply it to our own work or experience. We each thought about an example of a conservation project and brainstormed how the different parts of the social-ecological system fit into our example, such as the resource units, resource system, users and their links to the resource, governance, conservation actions/projects, and unintended consequences. Conservation goes beyond just the species – this showed us how complex real-world conservation is and all of the different things to consider as conservationists.

We also learned about conservation actors and projects, as well as the need for science and data in conservation, led by Dr. PJ Stephenson, the Chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Species Monitoring Specialist Group. In the 21st century, the main actors in conservation are governments, civil society and NGOs, conservation donors, academia, and business and industry. Conservation projects typically focus on reducing direct threats to biodiversity (such as habitat loss, pollution, and climate change) through conservation actions (such as land management, conservation planning, research and monitoring, and awareness raising). Therefore, we need biodiversity data to manage, protect, and restore wildlife and ecosystems. This not only includes species distributions and abundance, but also ecosystem services, threats and pressures, and the success of our conservation actions. However, biodiversity data is typically biased towards temperate and terrestrial ecosystems, and charismatic taxa like birds and mammals. We explored a few case studies to see real-world examples of how biodiversity data can be used in conservation, as well as ways to fill biodiversity data gaps.

IUCN Red List of Species

Young conservationists from different parts of the globe were given a golden opportunity to heighten their skills and knowledge on Red-Listing species and learn from the expert, Olivier Hasinger, in the 2-day vigorous workshop at UNIL. He took us through learning basic terminologies to in-depth knowledge on different criteria and categories of the Red List assessment. Practical work at the end of each day gave us a lot of insight on the level of understanding that is needed to be a Red List assessor and reviewer. Solving case studies in groups and having a mini competition was quite thrilling, plus the reward in the end was worth it.

Red List assessments incorporate other skill sets that are needed to fully assess a species and assign it in a particular category. Skills such as calculation of generation length, use of a GIS software like ArcGIS and other free online tools such as R, are used to produce species range maps and to calculate assessment metrics, namely area of occupancy (AOO) and extent of occurrence (EOO). Moreover, we learned how to use open-access data repositories like iNaturalist or Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), depending on the species, to obtain species distribution estimations. Through this process, we learned about the benefits, as well as the potential drawbacks, of these data sources for species mapping. This training helped us, as young researchers from diverse backgrounds, to understand data gaps that need to be filled to conserve particular species at regional and national levels.

Though from different parts of the world, we are all working with the same aim to protect and conserve species and their habitats. In some parts of the world there is insufficient knowledge, lack of expertise and resources to conduct surveys and protect species. This has had serious consequences in establishing conservation priorities and managing these species, which may further accelerate extinction risks of these species. This Red Listing course has paved a path of knowledge that will contribute towards protecting our unique study species and also other underrepresented global taxa and their habitats in the long run.

Other IUCN Tools

After an interesting and interactive case study on IUCN Red List species assessment, we visited the IUCN Headquarters in Gland on the afternoon of day three. We had the privilege to visit the IUCN library with Daisy Larios, which holds great collections of the world’s accumulated knowledge on nature conservation. The visit was followed by presentations by IUCN Staff members Ulrika Åberg, Katherine Zischka, Jennifer Kelleher, and Nadime Saleem, who shared their experience, career path in conservation and different case studies of conservation projects around the world. We were exposed to different conservation tools ranging from the IUCN Green List, which sets a standard and celebrates successful nature conservation work, to Other Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs) as a more inclusive approach to conserve biodiversity. Different conservation tools are developed to address the complexity of different challenges under various circumstances.

The final session shared about projects working together with indigenous peoples and local communities (IPCL) on conservation has shown us different facets of on-the-ground conservation works besides research. Working together with different people is just as vital for making nature conservation inclusive and preserving nature’s linkage with people. The sharing sessions depict the importance of transdisciplinary approaches and the value for systematic appraisal of evidence from different disciplines to make decisions in conservation practices. The visit was truly an eye-opening experience for us to see how research, species, nature and people come together, and unfold into conservation actions that make changes.

Species Distribution Modelling for Conservation

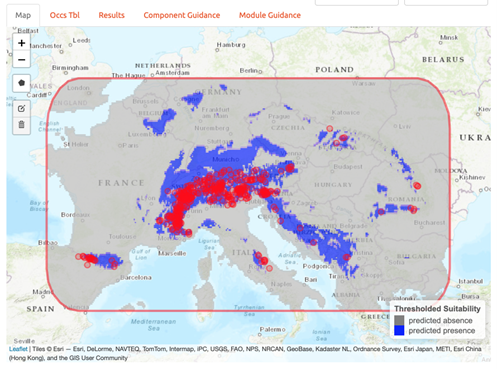

On the fourth day of our course, we discussed the use of species distribution modelling in the context of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and other applications in conservation. Our day started early with a lecture from Prof. Antoine Guisan, an expert in spatial predictive modelling of plant and animal distributions at UNIL, followed by a practical computer session led by Drs. Federico Riva and Luca Bütikofer. During the practical session, we practiced modelling a species and calculating its area of occupancy (AOO) and extent of occurrence (EOO), two factors that are considered when assessing a species for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

A theme throughout the summer school has been the ongoing biodiversity crisis. We need predictions of where biodiversity will occur in space and through time under the effects of climate change, which will provide the scientific basis for policy and decision support solutions. Due to incomplete biodiversity data across the globe (there’s no way that we can sample and monitor every single species in every single region of the world every single year), we rely on models to “spatialize” biodiversity information and predict where species occur across an area depending on their niche requirements. These concepts were not unfamiliar to many of us, but it was the first time for many to run species distribution models ourselves. Not only can species distribution models help us determine where species are likely to occur, but we can also determine species range changes over time and, more practically, determine where we should plan to create protected areas to preserve biodiversity.

Species Monitoring

Last, but not least, the final chunk of our course revolved around species monitoring. Indeed, monitoring species and ecosystems remains crucial. Ultimately, we do still need field data to explore trends, feed models, check projections, monitor the effect of conservation actions, evaluate the management plans of protected areas, and more. Nowadays, we still observe important taxonomic and geographic biases in monitoring practice, with more data (and funds spent) on flagship species and in the Western world. It is imperative to bridge these ‘monitoring gaps’ by including more regions and taxa. Yet different taxa will not be monitored in the same way, hence the existence of a variety of methods and protocols to choose from.

We had the chance to meet Dr Pascal Vittoz, keen botanist and senior lecturer at UNIL, who dedicated his intervention to the monitoring of plants in Switzerland. As is the case for most taxa and contexts, there is no perfect method to monitor complete plant communities, so choices have to be made based on the objectives of the project. We learned about various approaches to track changes in plant communities, each with their advantages and shortcomings, and about different Swiss long-term plant monitoring initiatives, including the rise of citizen science to collect data. However, monitoring taxa is not enough: we also need to track biodiversity drivers, such as environmental conditions and management, to be able to interpret and understand trends. A complete monitoring programme should therefore also include ecological data (e.g., soil parameters, climatic variables, disturbance regime…) and not forget to look at past as well as present conditions, because we often observe a delay in biodiversity responses.

Guided by Dr. PJ Stephenson, who we had met on Day 1 to talk about conservation actors and conservation data, we worked in teams to try to come up with monitoring plans for fictional projects with various objectives and contexts, such as reducing poaching of diverse animals in the Congo basin or improving the protection of marine mammals in the Arctic. Developing a sound monitoring plan calls for a deep understanding of the context, aims, needs and means of a project. What, How, Where, When and Who? These are the main questions guiding this process, and they are notably rooted in socio-economic contexts (available funds and skills, social values – what is deemed important at that place and that moment in time). This felt like coming full circle, back to the first day of the course, looking at the importance of integrating different knowledge systems, stakeholders and disciplines to practice a more inclusive and effective conservation.

We also got a small taste of what mammal monitoring can look like in the field. PJ led us to a local wood to set up a camera trap, a tool quite exciting and high-tech to some of us used to counting plants and invertebrates. After braving the rain and slippery slopes on Thursday evening to set the trap, we were rewarded the following morning with images of a fox – a lovely way to start our last day!

In and Around Lausanne

A few students explored Lausanne in their free time. It was a new city for almost everyone!

While in Lausanne, I took the opportunity to visit Aquatis – Aquarium vivarium. It was a spectacular sight – from fishes to amphibians and reptiles. For all the species on display, their red list status was provided, putting this very much in the perspective of the summer school course. The tour around the aquarium on display ended with a view of a tropical garden.

Bismark

Besides being a week of learning, it was also an opportunity to get to know a bit of Switzerland. In this case Lausanne, a city with incredible views of Lake Geneva along with the Alps and also, the beautiful architecture that holds a vast history of the city and the country.

Melissa

Conclusion

This summer school and the people we met will remain in our memories and will be part of our professional life, as it has opened the doors to a new world of possibilities related to biology and, in this case, conservation. It helped us see broader perspectives to our work, bringing to light the conservation potential of our own research. We gained new perspectives from all over the world to see conservation as a global concern and effort.

This was an experience that was not only professional, but also human, with great interactions and exchanges among the students and with the instructors. We were able to learn and express our ideas in a safe and welcoming environment with other like-minded scientists. This week allowed us to (re)think and learn about different topics related to IUCN Red List methodology, species monitoring, ecological niche modelling, and project approaches for conservation. Not only biodiversity, but the diversity of this course also allowed us to see a bit of the world without having to leave a classroom.