Jean-François (Jeff) Van de Poël – Ongoing research project, status update June 2025

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

AI can be a supportive tool with considerable potential, but its use without a framework can also have adverse effects on cognition and pedagogy. Below, we address three key issues: the illusion of mastery, the role of AI as an educational tutor, and the impact on academic output (homework, assignments) between legitimate assistance and problematic substitution.

Illusion of control and the need for critical thinking

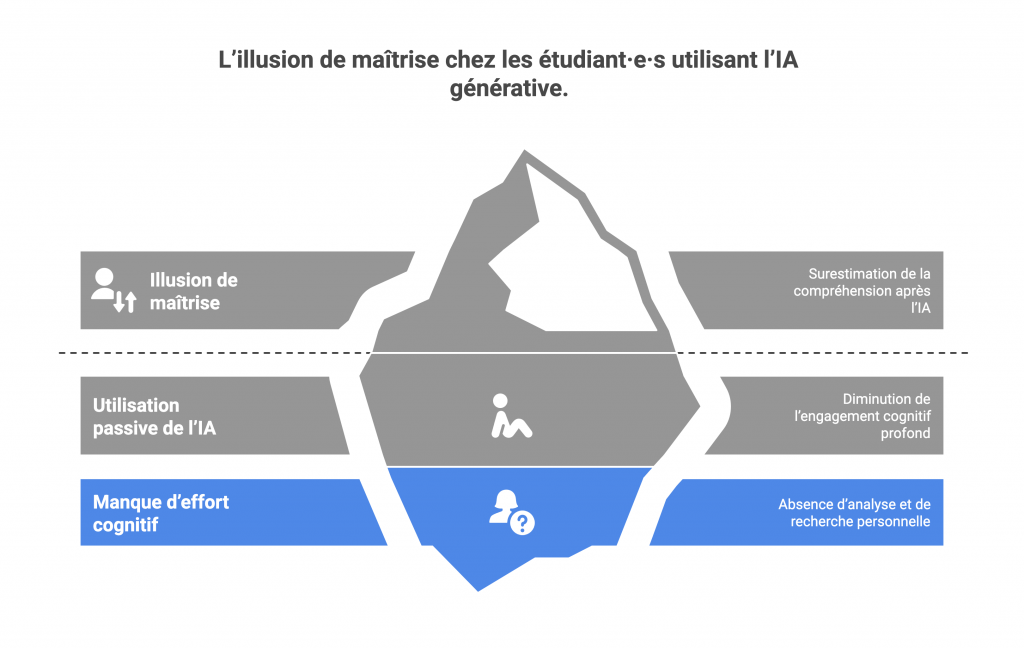

One of the first pitfalls observed is the risk of students using generative AI developing a false sense of mastery. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the ‘feeling of knowing’, refers to the tendency to overestimate one’s understanding after easily obtaining a well-formulated answer from AI.

Indeed, when faced with a fluid and coherent explanation provided by ChatGPT, a student may feel that they know and understand the concept, when in reality they have not made the cognitive effort necessary to truly grasp the notion. AI can thus reinforce a false sense of competence: learners believe they have mastered the subject because they have an immediate answer, without having had to analyse or search for it themselves.

In practical terms, this passive use of AI risks reducing engagement in deep cognitive processes that are essential for sustainable learning.

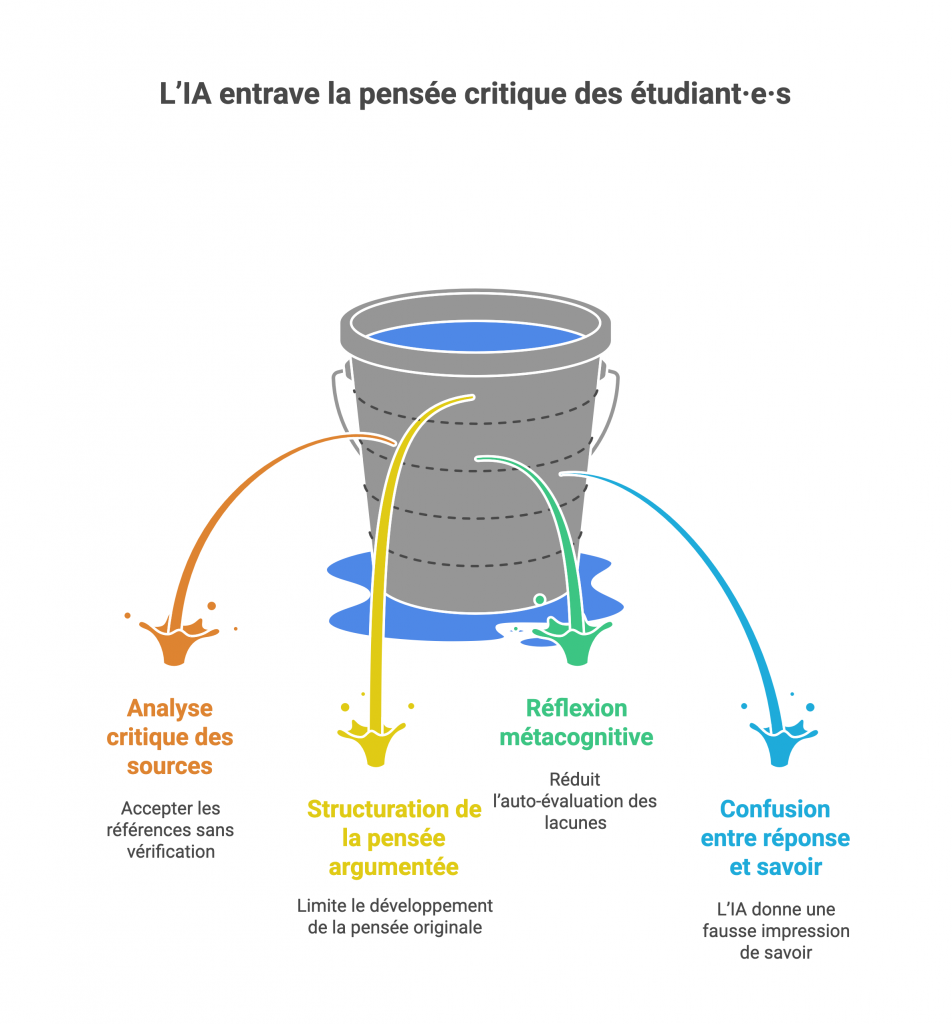

Among the processes that AI could bypass are:

- Critical analysis of sources. If AI provides an answer with references, students may be tempted to accept them without checking them. However, it is well known that AI can generate false references or inaccurate citations mixed in with real ones. Without systematic verification by the learner, there is a risk of reinforcing erroneous or unfounded knowledge. Critical thinking should prompt questions such as: Where does this information come from? Is it corroborated elsewhere?

- The structuring of reasoned thinking. By offering ready-made explanations or ‘turnkey’ arguments, AI can limit the development of students’ critical and original thinking. If every time we ask a question, we get a well-crafted essay, we deprive ourselves of the intellectual exercise of constructing our own reasoning, weighing the pros and cons, and finding our own examples. Ultimately, this can reduce one’s ability to argue independently and innovatively.

- Metacognitive reflection on learning. Learning is reinforced when students take the time to reflect on their own understanding: what do I not understand? How can I improve? If AI provides an immediate answer, learners are less likely to practise self-assessment of their weaknesses. The habit of taking the easy way out can undermine the ability to identify what one does not know and to plan strategies for learning. Thus, AI can give students the illusion that they have acquired knowledge when no real reasoning has taken place within them.

- The danger lies in confusing ‘answers obtained’ with ‘knowledge acquired’. That is why it is essential to train users (students and teachers) in the conscious and controlled use of AI, adopting an attitude of systematic verification and questioning.

- In practice, this means encouraging students to question AI responses, verify their reliability (for example, by checking the references provided), and use them as a starting point for reflection rather than as absolute truth. As the University of Fribourg points out, the tool should not be banned, but rather students should learn to work with it while checking the results it produces, because ‘they are not always correct and cannot replace the complex thinking that a human being is capable of’.

- The use of AI must therefore be accompanied by metacognition: students should ask themselves how AI has helped them, and what they might have missed without their own critical thinking skills.

In short, to avoid the illusion of control, teachers play a key role as guardians of critical thinking. Students should be made aware of the limitations of AI, trained to validate information (by cross-checking it with the course material or other sources), and given activities that force them to go beyond simply copying the answer provided by the machine (see following sections). AI should be presented as a support tool and not as an infallible oracle. This education in critical thinking about AI is in line with the concept of AI literacy, which aims to give everyone the keys to using these tools intelligently (Anders, 2023).

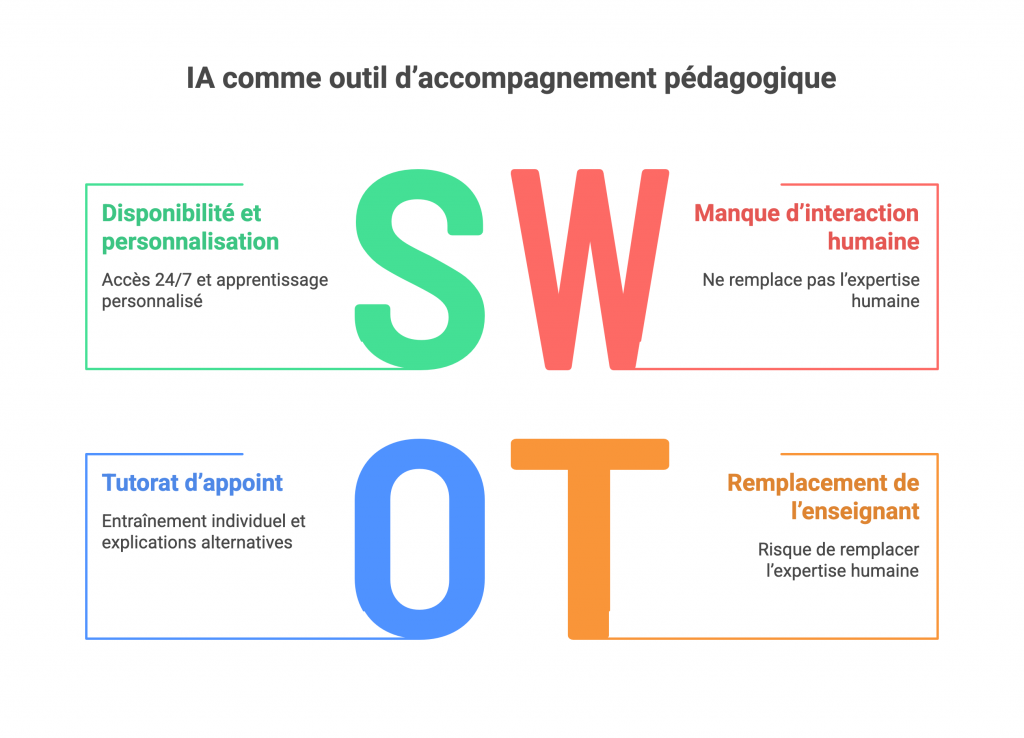

AI as an educational support tool (virtual tutor)

Another emerging use of AI in education is as a virtual tutor or teaching assistant. In theory, a sophisticated conversational agent can be available 24 hours a day to answer students’ questions, re-explain a concept, provide additional examples, or even guide the learner step by step through the process of solving a problem.

This echoes psychologist Vygotsky’s ideas on the zone of proximal development: a tool capable of providing assistance just above the student’s current level could help them progress. Generative AI has the potential to offer a form of assistance: it can provide explanations, answer questions, structure a learning path, and even help students produce study and revision materials (flashcards, summaries).

Ideally, we could imagine a personalised chatbot tutor for each student, instantly filling in certain gaps or suggesting tailored exercises. However, this attractive vision of an AI “mentor” must be strongly tempered by the reality of its educational and socio-emotional limitations.

In practice, several risks arise when using AI as a tutor:

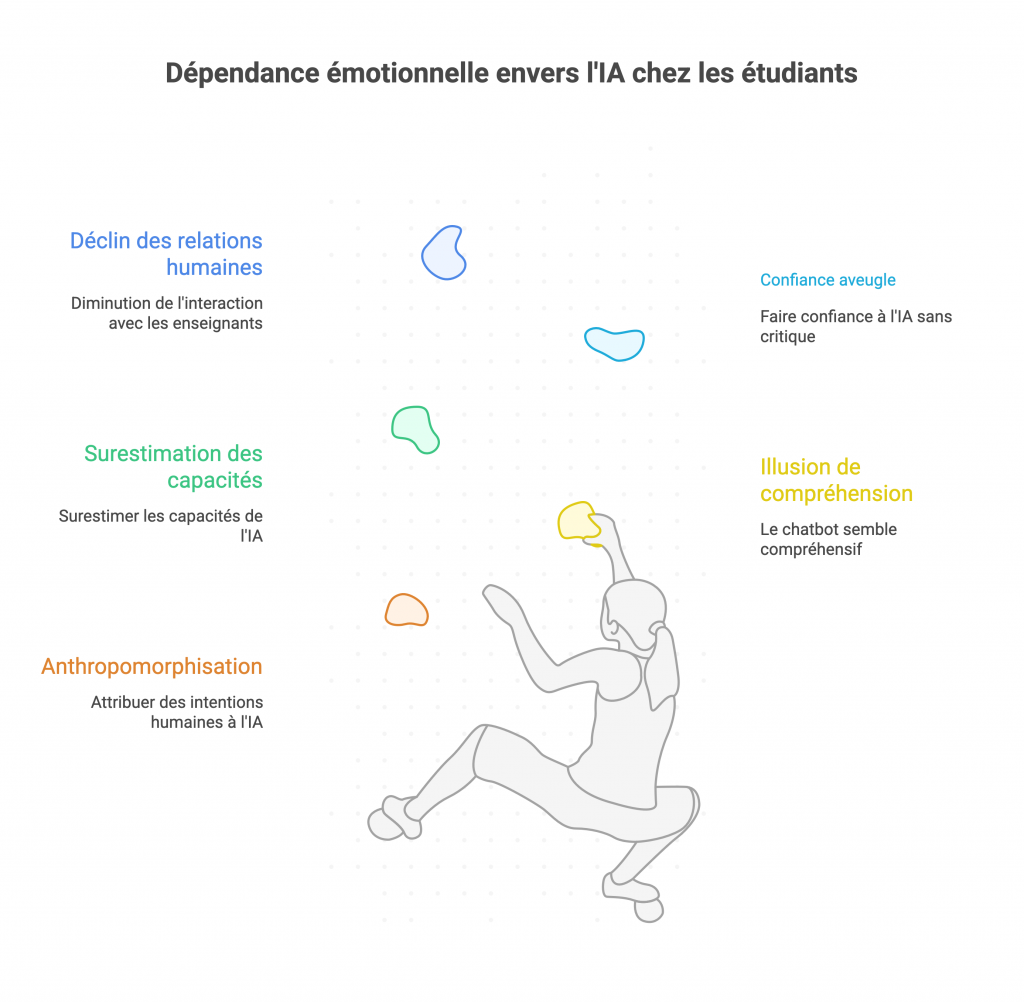

- Anthropomorphisation and emotional dependence. Students tend to anthropomorphise AI, i.e. to attribute intentions or intelligence to it that it does not possess. A polite and encouraging chatbot can give the illusion of an understanding interlocutor. Some students may then develop a socio-emotional dependence on AI, perceiving it as a benevolent mentor, when in fact it is only an algorithm with no real consciousness or empathy. This illusion of an educational relationship can lead to overestimating the capabilities of AI and placing blind trust in it, to the detriment of the relationship with the human teacher.

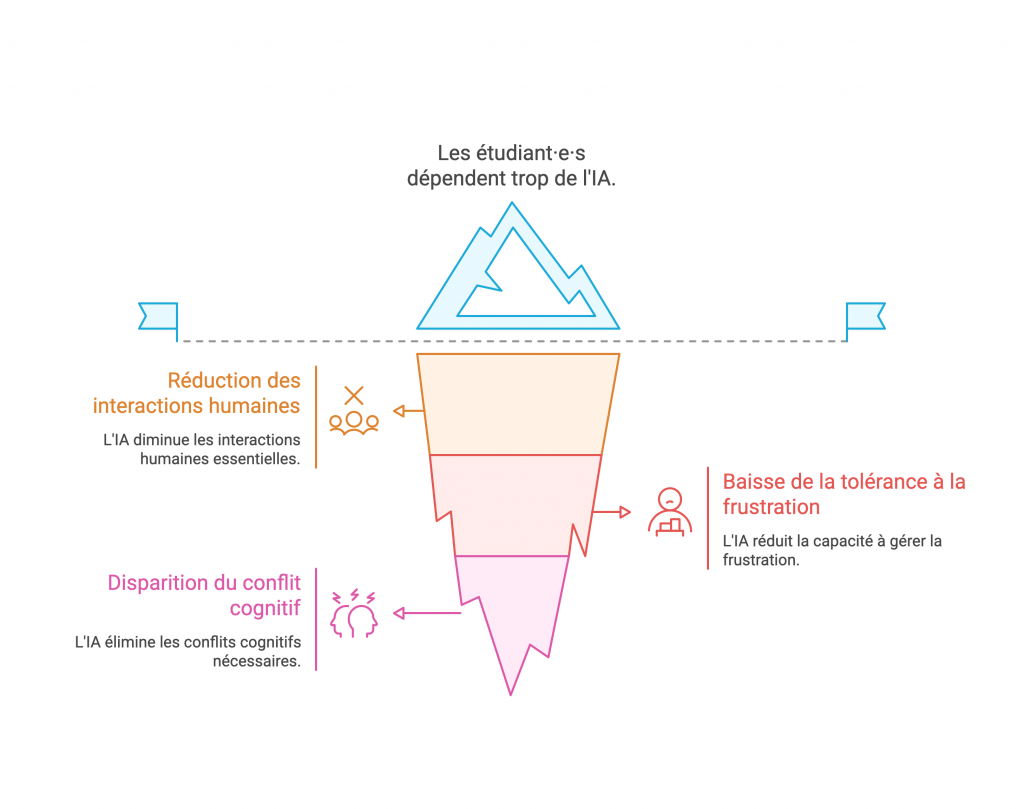

- Reduced human interaction. If AI answers all questions, students may be less likely to ask their teachers for help or discuss topics with their classmates. However, we know that human educational dialogue – with teachers or in groups with peers – is essential for in-depth learning. Replacing these rich exchanges with interactions with AI risks impoverishing the interactive and reflective dimension of the learning process. For example, a student preparing for an exam will no longer ask questions in class or participate in discussion forums because they can already get all their answers via ChatGPT. In doing so, they deprive themselves of the additional insights, debates and personalised feedback that a teacher or other learners could provide.

- Decreased tolerance for frustration. A human teacher knows that sometimes it is necessary to challenge students, to push them to seek answers on their own, even at the risk of them making mistakes and learning from them. This productive management of frustration is part of the educational process (we also learn by encountering problems). AI, on the other hand, tends to provide immediate answers and smooth out difficulties. By constantly obtaining instant solutions, students may lose the habit of persevering with complex concepts. Their cognitive resilience and ability to sustain effort may diminish, which is problematic when tackling difficult tasks that require patience and reflection.

- Disappearance of cognitive conflict. Socioconstructivist theories of learning emphasise the importance of cognitive conflict: it is often by confronting different ideas, debating, and making mistakes that we build new, more solid knowledge. However, conversational AI, by design, generally seeks to provide concise, neutral and uncontroversial answers (it avoids taking sides or expressing strong disagreement, unless explicitly asked to do so). This means that AI often produces consensual answers that do not provoke contradiction. A student who is content to interact with AI will not experience the healthy confrontation of ideas that they would have had in a debate with a teacher or a peer with a different point of view. The risk is that they will believe they have a thorough understanding of the subject when in fact they have not had to question their own initial ideas due to the lack of contradiction from the AI. In short, AI can smooth over debates and give a misleading impression of ‘well-organised’ knowledge, whereas learning often benefits from being a somewhat chaotic process involving disagreements and questioning.

AI and academic production: between assistance and substitution

A third impact of AI in higher education concerns the production of academic work (assignments, reports, dissertations, etc.) by students. ChatGPT and similar programmes can now generate essays, computer code, summaries, etc., with such ease that some students are tempted to use them to do (or help do) their written work. This raises a whole series of educational and ethical questions: what is the point of learning if AI does the work for the student? How can the student’s contribution be assessed? Is it plagiarism or cheating? Should it be banned or allowed? In this section, we will first examine the cognitive risks of excessive reliance on AI, then the issues of academic integrity, before looking at strategies that can be adopted to strike a balance between beneficial and problematic uses of AI in student work.

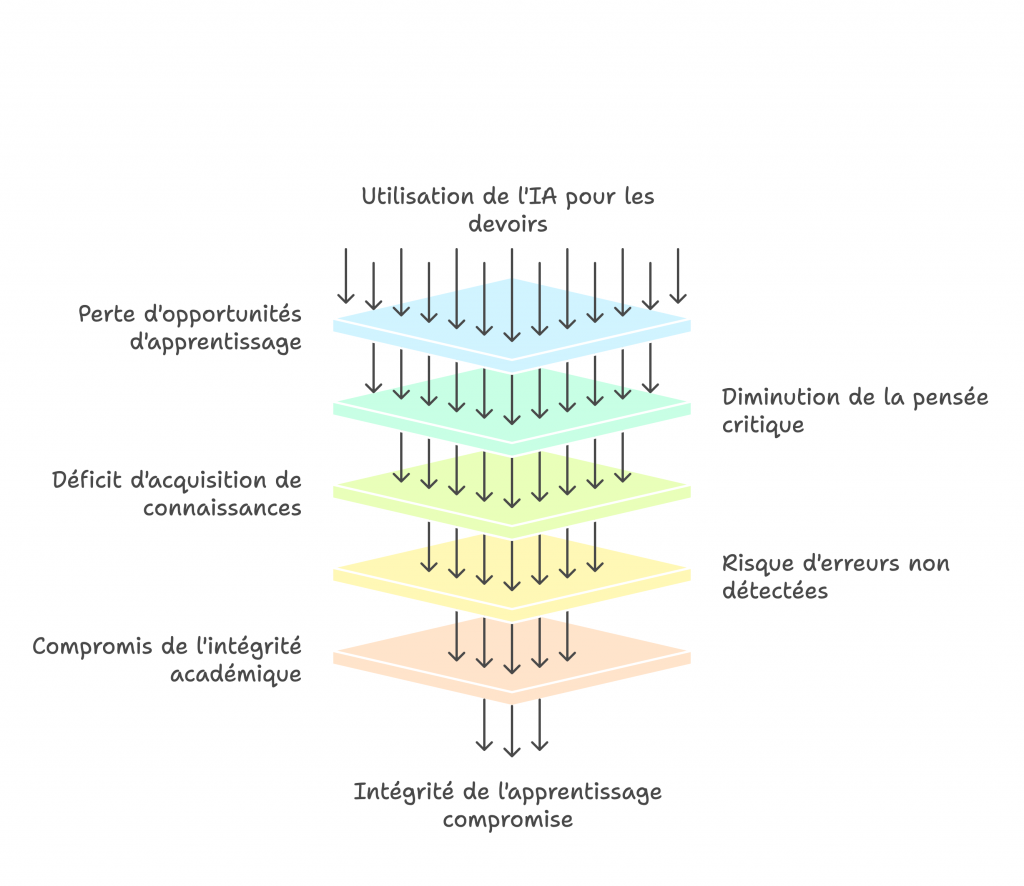

- Cognitive risks and the ‘delegation’ of intellectual work. Entrusting AI with the task of writing an assignment for you may seem like a time-saver, but it is above all a lost learning opportunity for the student. By letting AI do the work, students are giving up part of the intellectual process that was the aim of the exercise.

- Intellectual passivity and failure to internalise knowledge. When AI writes an essay or paper, students do not internalise the concepts used. They have not had to rephrase them in their own words, search for information, select it and then summarise it. However, it is precisely by making this effort to rephrase and structure that knowledge is consolidated. AI provides a finished product, but the student has not gone through the thought process that builds knowledge. This leads to a decline in critical thinking, as the student accepts the generated text without question. There is also a deficit in knowledge acquisition: not having actively manipulated ideas means running the risk of quickly forgetting them or not knowing how to apply them in a different context.

- By delegating writing tasks, students lose practice in fundamental skills such as documentary research, information analysis and synthesis, and the logical structuring of a piece of writing. Yet these writing skills are essential for structuring and communicating ideas, and prove invaluable far beyond university. In short, using AI as a cognitive shortcut deprives students of the very exercise that was the educational goal of the assessment.

- The ‘plausibility factory’ and the risk of undetected errors. Generative AI models excel at producing fluent and plausible text. However, plausible does not mean accurate. AI can incorporate subtle errors (incorrect dates, biased interpretations, false calculations) into an assignment while maintaining a convincing style. A student unfamiliar with the subject may not notice these errors and submit work containing falsehoods. In doing so, they incorporate these errors into their own understanding of the subject, validating them simply by using them. This is the risk of cognitive contamination: by reading and rereading an erroneous text in order to refine it, one ends up believing its content. AI is a factory of plausibility: it will always give you something that “sounds” true. This requires even greater vigilance on the part of the student (and the teacher who will be marking the work) to uncover any hidden errors. Students who rely on AI must therefore be trained to critically re-read what the AI produces, which is no easy task when you are new to a field.

- Violation of academic integrity. From an ethical standpoint, if a piece of work is submitted as personal work when it has been largely written by AI, this could be considered fraud or, at the very least, academic dishonesty. This raises the question: is a text produced by AI and used as is considered plagiarism or cheating? Not all current academic rules have anticipated this scenario. It is becoming urgent for higher education institutions to clarify their position on this issue. At the very least, it seems necessary to distinguish between legitimate uses (e.g. using AI as a source of inspiration, for proofreading, or for brainstorming ideas) and problematic uses (e.g. generating an entire assignment and submitting it as if it were one’s own work). Without this, students are left in a grey area, with some thinking they are doing nothing wrong by relying ‘a little too much’ on AI, while others may feel guilty, perhaps unjustifiably, for simply using spelling assistance.

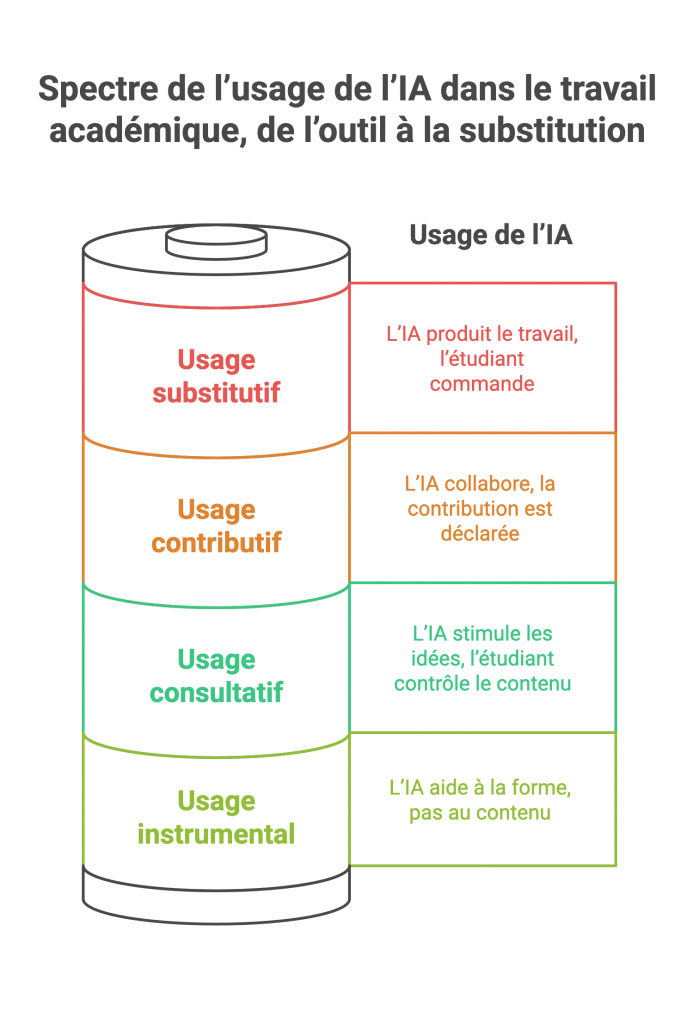

The above points show that the boundaries between original creation, assistance and cognitive delegation are becoming blurred in the age of AI. Rather than thinking in terms of all or nothing (either allowing AI completely or banning it entirely), it makes more sense to adopt a nuanced approach. Experts propose developing a gradation of AI uses in academic work.

For example, we can distinguish between:

- Instrumental use: AI is used as a technical tool with no impact on the intellectual content of the work. Examples: correcting spelling/grammar, formatting text, checking references. This use is comparable to software such as Grammarly or Antidote, which does not contribute ideas but simply helps with form. This use is generally considered acceptable, in the same way as using an automatic spell checker.

- Advisory use: AI serves as a brainstorming partner to stimulate ideas, without replacing the author. For example, students chat with ChatGPT to gather ideas on a topic and ask questions to clarify a concept, but ultimately write the final text in their own words and with their own ideas. Here, AI is a kind of intellectual sparring partner, which can be seen as acceptable (some may even see it as a form of learning) as long as the student remains in control of the content.

- Contributory use: AI is an acknowledged collaborator, generating a significant portion of the content, but this contribution is supervised and declared. For example, a student may ask the AI to write an explanatory paragraph that they will then include in their assignment, clearly indicating this (‘paragraph generated with this tool, reviewed by me’). This could be likened to a co-authoring effort between the student and the AI. This is obviously a delicate area: it goes beyond a purely personal exercise, but if it is done transparently and under supervision (and, for example, authorised by the teacher for this specific exercise), it could be accepted in certain contexts. The assessment would then need to be adapted accordingly (see section 5 on assessment).

- Substitutive use: AI is the main producer of the work, with the student essentially acting as the client. This is the case with an assignment written almost entirely by ChatGPT and submitted as is (or with very minor changes) by the student. Here, there is a clear delegation of intellectual work: the student has not accomplished the expected cognitive task, which poses a pedagogical problem (no real learning) and an ethical problem (a form of cheating). This use should be considered unacceptable in the context of graded work, in the same way as traditional plagiarism.

There may be gradations between these categories. The important thing is to explicitly set boundaries in each context (each course, each institution): what is allowed and what is not. For example, a teacher might say to their students: “For this assignment, you can use ChatGPT to help you find ideas (consultative use), but any generated text must be rewritten in your own words and may not be left as is (no substitute use). Another may allow contributory use on condition that the AI-generated draft is attached as an appendix and that a reflection on how the AI was used is written. Yet another may choose to ban AI entirely for a given assignment (including instrumental use) if the aim is to assess the student’s raw ability without assistance.