Why do some ancient animals become fossils while others disappear without a trace? A new study from the University of Lausanne, published in Nature Communications, reveals that part of the answer lies in the body itself. The research shows that an animal’s size and chemical makeup can play an important role in determining whether it’s preserved for millions of years—or lost to time.

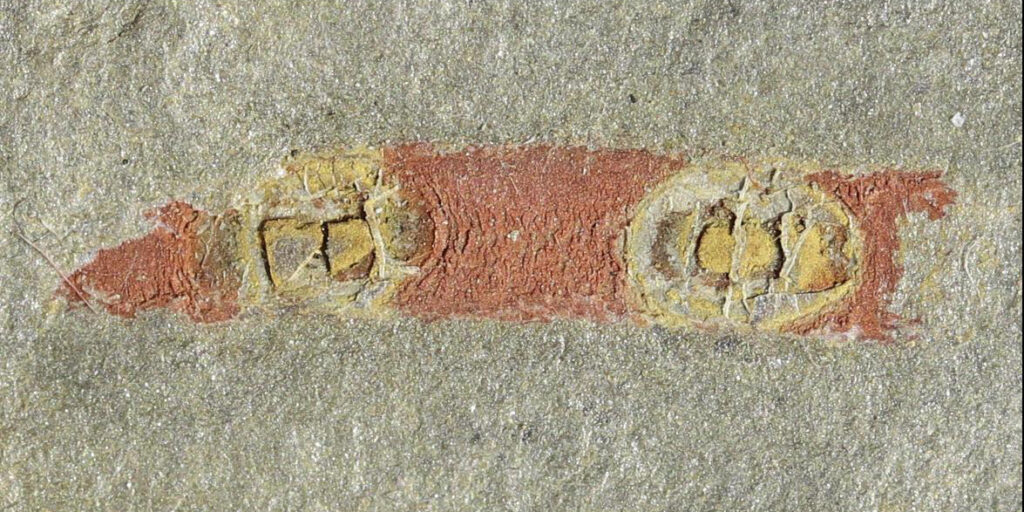

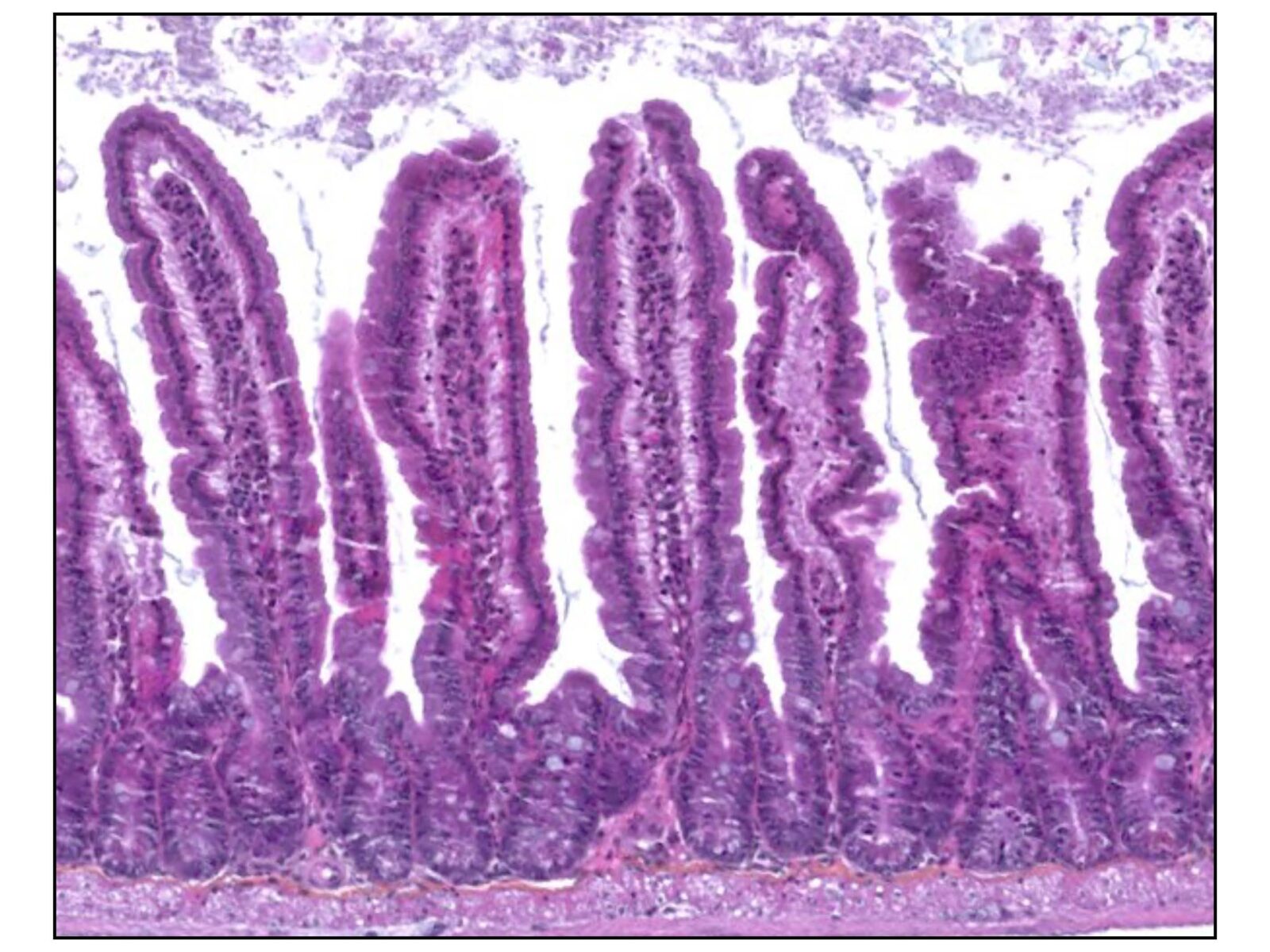

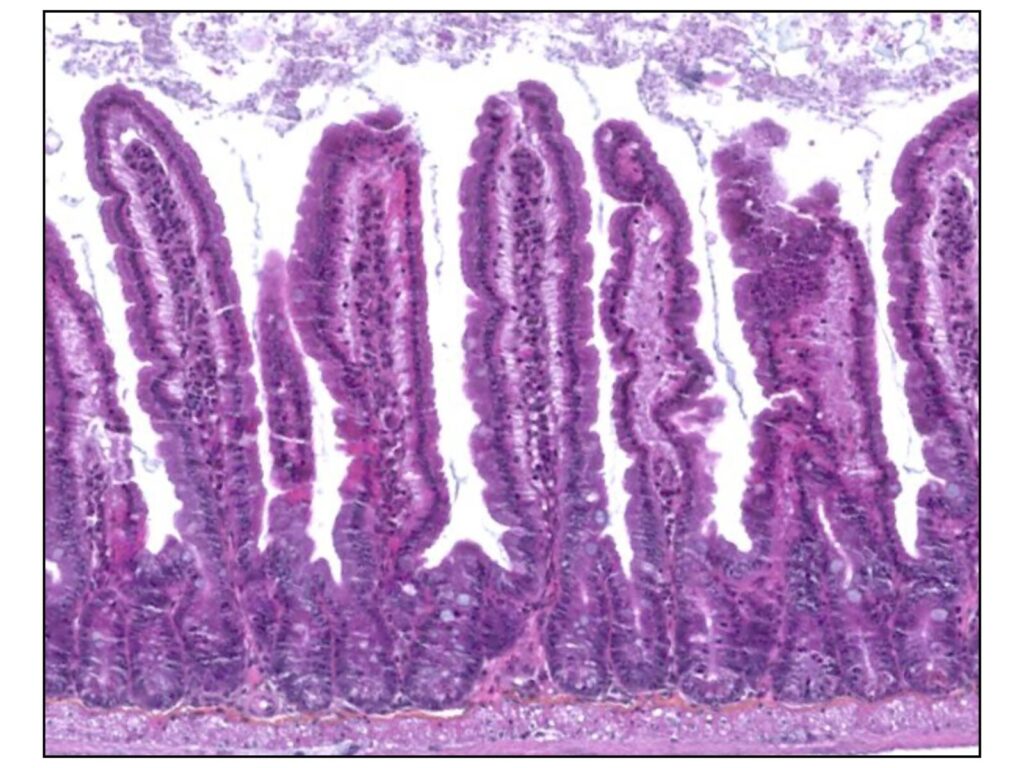

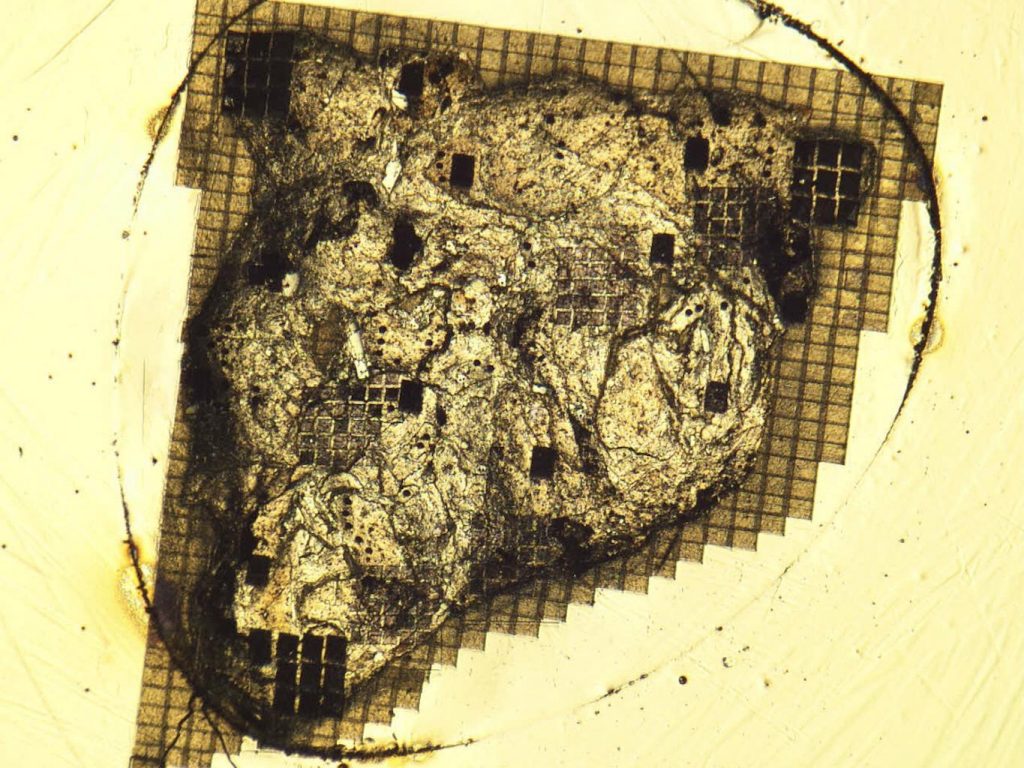

Fossils are more than just bones; some of the most remarkable finds include traces of soft tissues like muscles, guts, and even brains. These rare fossils offer vivid glimpses into the past, but scientists have long puzzled over why such preservation happens only for certain animals and organs but not others.

To dig into this mystery, a team of scientists from the University of Lausanne (UNIL) in Switzerland turned to the lab. They conducted state-of-the-art decay experiments, allowing a range of animals including shrimps, snails, starfish, and planarians (worms) to decompose under precisely controlled conditions. As the bodies broke down, the researchers used micro-sensors to monitor the surrounding chemical environment, particularly the balance between oxygen-rich (oxidizing) and oxygen-poor (reducing) conditions.

The results were striking and have now been published in Nature Communications . The researchers discovered that larger animals and those with a higher protein content tend to create reducing (oxygen-poor) conditions more rapidly. These conditions are crucial for fossilization because they slow down decay and trigger chemical reactions such as mineralization or tissue replacement by more durable minerals.

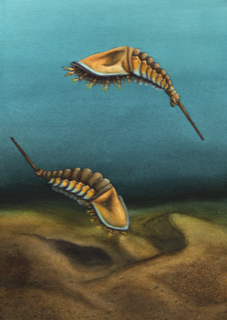

“This means that, in nature, two animals buried side by side could have vastly different fates as fossils, simply because of differences in size or body chemistry,” affirms Nora Corthésy, PhD student at UNIL and lead author of the study. “One might vanish entirely, while the other could be immortalized in stone” adds Farid Saleh, Swiss National Science Foundation Ambizione Fellow at UNIL, and Senior author of the paper. According to this study, animals such as large arthropods are more likely to be preserved than small planarians or other aquatic worms. “This could explain why fossil communities dating from the Cambrian and Ordovician periods (around 500 million years ago) are dominated by arthropods,” states Nora Corthésy.

These findings not only help explain the patchy nature of the fossil record but also offer valuable insight into the chemical processes that shape what ancient life we can reconstruct today. Pinpointing the factors that drive soft-tissue fossilization, brings us closer to understanding how exceptional fossils form—and why we only see fragments of the past.

Source

N. Corthésy, J. B. Antcliffe, and F. Saleh, Taxon-specific redox conditions control fossilisation pathways, Nature Communications, 2025

Research fundings

SNF Ambizione Grant (PZ00P2_209102)

Questions to Nora Corthésy,

principal author of the study at UNIL

Why did you choose shrimps, snails and starfish to conduct your study?

These present-day animals were the best representatives of extinct animals we had in the lab. From a phylogenetic (relationship between species) and compositional point of view, they are close to certain animals of the past. The composition of the cuticles and appendages of modern shrimps, for example, is more or less similar to that of ancient arthropods.

How can we know that animals lived, then disappeared without a trace, if we have no evidence of this?

When studying preservation in the laboratory, it becomes possible to distinguish between ecological and preservational absences in the fossil record. If an animal decays rapidly, its absence is likely due to poor preservation. If it decays slowly, its absence is more likely to be ecological, that is, a true absence from the original ecosystem. Our study shows that larger, protein-rich organisms are more likely to be preserved and turned into fossils. We can therefore hypothesize that smaller, less protein-rich organisms, which have very little chance of dropping their redox potential, may not have been fossilized due to preservational reasons. It is therefore possible that some organisms could never have been preserved, and that we may never, or only with great difficulty, be able to observe them. Nevertheless, all of this remains hypothetical, as we are unable to travel back in time millions of years to confirm exactly what lived in these ancient ecosystems.

What about the external conditions in which fossils are formed, such as climate?

The effect of these conditions is very complicated to understand since it is nearly impossible to replicate ancient climatic conditions in the laboratory. Nevertheless, we know that certain sediments can facilitate the preservation of organic matter, giving clues as to which deposits are the most favorable for finding fossils. We also know that factors such as salinity and temperature, also play a role in preservation. For example, high salinity can increase an organism’s preservation potential, as large amounts of salt slow down decay in a similar way to low temperatures. Our study here focuses solely on the effect of organic matter and organism size on redox conditions around a carcass. It is therefore one indicator among others, and there is still a lot that needs to be done to understand the impact of various natural conditions on fossil preservation.