Original text published on : https://wp.unil.ch/geoblog/2024/03/cartographier-et-predire-les-risques-naturels-de-maniere-plus-fiable-grace-aux-algorithmes/

Modelling natural hazards is an essential task for protecting populations and territories. Marj Tonini, director of the Swiss Geocomputing Centre at UNIL, integrates artificial intelligence into her models to improve the reliability of risk maps. Harnessing the power of machine learning and an ever-growing pool of environmental data, she pushes beyond the limits of traditional methods, which were once slow and subjective. Her predictive models, now adopted across Europe, have become a benchmark and pave the way for a more dynamic, collaborative, and forward-looking approach to mapping.

A Surge of Data Enabling AI Integration into Models

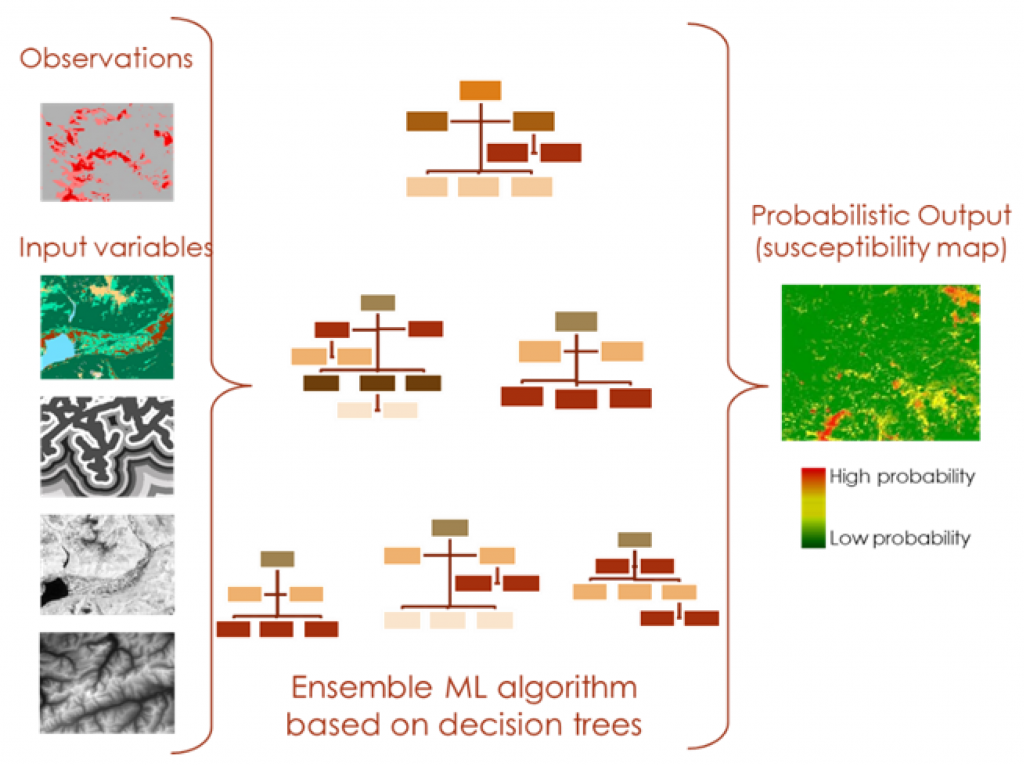

At the start of her research, Marj Tonini worked with “classical” mapping models. These models rely on solid environmental knowledge, with each area described by numerous parameters — such as slope, soil type, and vegetation cover. To assess wildfire risk, for instance, these variables are weighted according to their relative influence on the phenomenon (e.g., vegetation type or land use). As Tonini explains, “These models have the drawback of relying on the scientists’ subjectivity, who decide how much weight to assign to each variable, and they require a great deal of time to test different configurations.”

Marj Tonini turned to machine learning at a moment when several key developments supported the shift. “The use of artificial intelligence in my models was made possible by the massive increase in available data — such as digital spatio-temporal databases and satellite imagery — as well as by the growing computational power of computers.” she explains.

The algorithms used made calculations far more efficient, allowing her to more easily work with multiple variables and refine her models. Predictions for areas lacking direct data (see box) were thus improved. Moreover, the ability to process random parameters enables the generation of risk occurrence maps — estimating the probability of a wildfire in a given area with a certain margin of uncertainty — which enhances the usability of the information for end users, such as local and regional authorities.

AI Still Has Room to Grow in the Field of Geosciences

According to Marj Tonini, “the use of AI in geosciences remains marginal (< 20% of geoscience research).” This percentage is expected to rise as machine learning techniques and data science become more integrated into core curricula for students and PhD candidates. Tonini, who teaches at the master’s level, observes a growing interest among her students to incorporate AI into their research projects. ” However, it is necessary to draw their attention to the pitfalls to avoid. For example, it is important to have sufficient data, to start with relevant questions, not to confuse correlation with causality, and to be able to verify the results using new data. “, illustrates the researcher.

Marj Tonini also points out that “AI can serve as a valuable catalyst for collaboration—for instance, between domain experts and machine learning specialists, or among scientists from different fields who apply similar algorithms to integrate AI into their research.” She herself collaborates with researchers from various disciplines, institutions, and countries.

From first publication to a European standard

“One example I can cite is my collaboration with the International Center for Environmental Monitoring in Italy (CIMA)“, explains Marj Tonini. ” One of their representatives contacted me following my first publication on the use of machine learning in a model designed to analyse the risk of forest fires. He had data collected over 30 years and wanted to know if it could be incorporated into my model. “, she recalls.

The CIMA group (in the “Wildfire Risk Management and Forest Conservation” division) had developed a highly sophisticated deterministic model, which they aimed to compare with models incorporating machine learning. Both approaches were tested using 80% of the available data, with projections made on the remaining 20% of independent data. The AI-based model significantly outperformed the more traditional deterministic one. According to Marj Tonini, “Following these results, the model was ultimately adopted as the standard for wildfire risk mapping developed at both local and European levels by the CIMA center.”

Dr. Marj Tonini, researcher and director of the Swiss Geocomputing Centre, studies the modelling of natural hazards such as forest fires and landslides, the production of predictive scenarios and changes in land use.

Faculty of Geosciences and Environment