Cette publication est également disponible en :

Français

Prof. Gretchen Walters recently joined Gabonese colleagues and international partners in Doumé to study and teach with them how past human activities are still influencing biodiversity in Gabon’s areas that may appear “natural”. This research aims to better manage and protect biodiversity, taking cultural and historical practices into account.

By Gretchen Walters

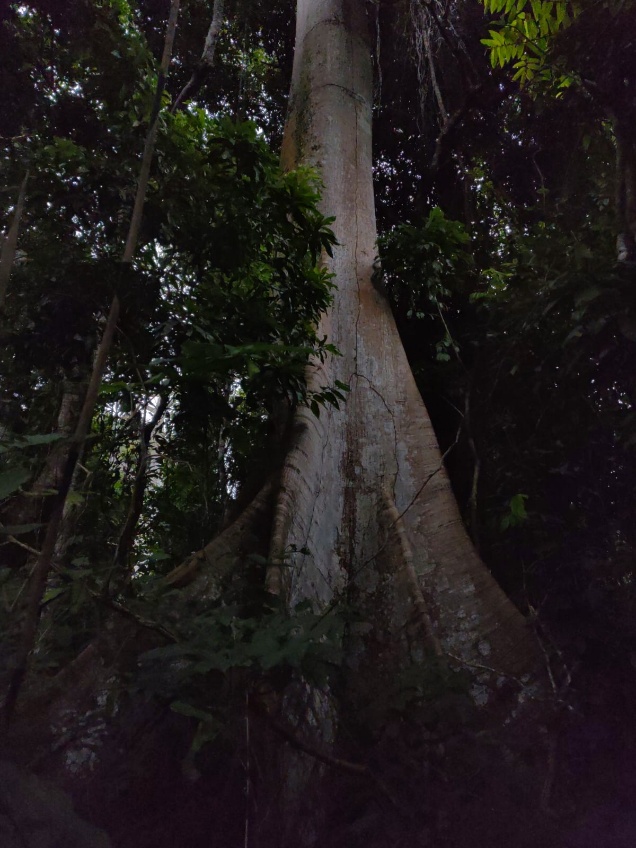

Viewing the forest and savannas from a plane or drone, the expansive ecosystems look almost uniform, and natural. But if one knows how to read the landscape, it’s a completely different story: the ecosystem bears the marks of its history in its flora, fauna, soil, and its people.

Studying biodiversity is at its best when it brings together different disciplines and stakeholders to understand the issues. In June and July 2025, Professor Gretchen Walters taught in the Ecole de Terrain “ECOTROP” in Gabon to students and professionals from the national parks agency, in collaboration with teachers from Gabon, France, the UK, the US, Swaziland, and Greece. The goal was to conduct research with students and teach tools and methodologies that would allow to understand the biodiversity of Gabon’s ancient villages which are scattered throughout the forest.

27 participants1 and several professors from the Université Omar Bongo (UOB, with which UNIL has an agreement), Université des sciences et techniques de Masuku (USTM), the Gabon national parks agency, and five American universities, set out together to find out.

Over the course of three weeks, we studied the biodiversity of former village sites in Gabon around the village of Doumé in collaboration with members of the Kota, Adouma, Bongo, and Awandji ethnic groups, who have lived in this forest-savanna mosaic at the edge of the Ogooué River for several hundred years.

Prof. Gretchen Walters

Gabon’s forests were previously extensively settled with villages and their associated territories occupying vast areas. However, during the colonization by France, villages were forced to move to the roadsides, in what is called the “Regroupement”, a process that occurred from 1919 to the 1970s. This far-reaching colonial policy displaced villages, but did not displace land use. People regularly return to these former villages and they still are part of village hunting territories and remain important for cultural reasons. However, most research does not account for these parts of the ecosystem, tending to focus on places which appear to have less human influence. Thus, this field school and the related FNS forest history project aims to fill these important gaps, and to account for how people have shaped the ecosystem over time.

In ECOTROP, participants become members of a one of the following thematic “ateliers”: archaeology, pedology, botany, zoology (birds and mammals), and participatory cartography. Each atelier is led by a researcher, and the results of each atelier contribute to answer our research questions about understanding the role of people in modifying soil and biodiversity. Using a variety of methods, each atelier documents the biodiversity, social history, and soils of a former village and a neighboring comparative site which has never had a village or an agricultural field. UNIL’s contribution to the field school is to bring an environmental anthropology approach using transdisciplinary methods, which collaborate with experts from the four ethnic groups of Doumé. While the field school is funded in part by an National Science Foundation grant from the US, UNIL’s participation is from a sister project, funded by the FNS, which also focuses on understanding the legacies of the past forest land use.

This year, we focused on the former villages of Mabouli and Manenga while the archaeology team worked in the nearby Youmbidi cave. Each team works with community members, but in the participatory historic cartography one, these community members become experts that we work with, since we are documenting their village histories.

During our fieldwork, our work was documented by Victor Amman, a graduate of UNIL who creates science documentaries. We look forward to seeing his film early next year!

When we are finished with our research, we present our findings back to the community members in Doumé and in the nearby cite of Lastoursville. This is an important step for participants to learn how to communicate their findings to the general public and most importantly, for the host communities to understand what we did. We look forward to working with them again next year.

ECOTROP is a field-based research class that has been held in Gabon and Cameroon since 2011.

The Consortium is led by the Gabon National Parks Agency in partnership with the USTM and UOB, along with numerous other universities outside of Gabon, but notably the University of New Orleans and the Institute of research and development of France. The field school is largely financed by a grant the United States National Science Foundation to the University of New Orleans and TOTAL. UNIL became a partner of the ECOTROP Consortium in 2025, and participates in ECOTROP as part of a wider FNS project on a related subject in Gabon.

- Participants are called “apprenants” because they may be university students or professionals from the national parks agency. ↩︎

Leave a Reply