Dans le cadre d’un projet de podcast, j’ai choisi d’explorer la réception ordinaire d’œuvres littéraires et filmiques, afin d’interroger la manière dont celles-ci peuvent raisonner avec le vécu de certaines personnes. Pour cet épisode, je me suis entretenue avec Sophie, dont la mère est atteinte de troubles neurocognitifs, ou maladie d’Alzheimer, afin de comprendre le rapport qu’elle entretenait avec des récits fictionnels ou (auto)biographiques traitant de cette maladie.

Notre entretien s’est construit autour de trois œuvres : Une femme (1988) d’Annie Ernaux, où l’autrice évoque dans les dernières pages la maladie de sa mère, The Father (2020) de Florian Zeller, un film qui donne à voir l’expérience intérieure d’un père dont la réalité s’effrite progressivement, et L’Homme qui tartinait une éponge (2018) de Colette Roumanoff, recueil d’histoires qui restituent l’intimité du quotidien des personnes atteintes d’Alzheimer.

Ce travail s’appuie également sur les recherches de la psychologue Pascale Peretti, qui mettent en évidence la fonction de la fiction comme espace de transformation psychique permettant de symboliser les pertes et de maintenir un lien avec les représentations intériorisées des autres (parents, proches, figures d’attachement), ainsi que sur les travaux de Jean-Marc Talpin et Odile Talpin-Jarrige, psychologue et psychiatre, qui soulignent le rôle des récits dans la légitimation des affects et la reconnaissance partagée des vécus liés à la maladie. Afin d’élargir ces perspectives, j’ai rencontré Cédric-C. Boven, psychologue associé du Service universitaire de Psychiatrie de l’âge avancé (SUPAA), spécialiste en psychothérapie, qui propose des consultations psychologiques pour proches aidants.

Les récits sont susceptibles d’interagir de différentes façons avec l’expérience de la maladie. Ils en interrogent par exemple les représentations collectives ou individuelles, en les confirmant, en les infirmant ou en les déplaçant. Leur réception peut ainsi favoriser la reconnaissance, la légitimation et parfois la transformation d’une expérience vécue. Ces récits peuvent par ailleurs jouer un rôle dans la préservation du lien entre la personne malade et ses proches, en s’avérant l’occasion d’un partage et de discussions à propos d’expériences intimes et douloureuses sur lesquelles il est difficile de mettre des mots. À ces dimensions relatives à la réception des fictions s’articule la production de nouveaux récits par des malades ou des proches, parfois en raison d’un besoin d’expression, parfois dans l’optique que ceux-ci pourront servir à d’autres.

Ce compte-rendu s’intéresse plus particulièrement à la façon dont l’apparition et l’évolution de la maladie entrainent des déplacements identitaires et sur la manière dont nous choisissons de nous raconter nos vies face à une expérience qui se fragmente.

Sophie

Puis elle a oublié l’ordre et le fonctionnement des choses. Ne plus savoir comment disposer les verres et les assiettes sur une table, éteindre la lumière d’une chambre (elle montait sur une chaise et essayait de dévisser l’ampoule). (Ernaux, 1988, p. 90)

C’est avec surprise que Sophie constate que cet évènement, raconté par Annie Ernaux, elle l’a vécu presque tel quel avec sa propre mère : une bouleversante façon de constater qu’autrui ne comprend plus comment fonctionne le monde. Progressivement, tout devient « trop compliqué, hors d’atteinte », écrit Colette Roumanoff, dans L’Homme qui tartinait une éponge (2018, p. 13), un titre qui renvoie à un autre type de décalage. Ce sont alors les proches qui deviennent garants du quotidien. Ce transfert de responsabilités les oblige à se redéfinir dans leur rapport à la personne malade. Les récits, en mettant en scène ce basculement, offrent une ressource précieuse, dans la mesure où ils proposent de mettre en mots une expérience souvent difficile à accepter ou même à exprimer. À cet égard, ils ouvrent un espace de recomposition identitaire : Pascale Peretti (2016) insiste sur la capacité des récits à reconfigurer l’expérience des publics et à nourrir « l’identité narrative[1] » des individus. Autrement dit, les récits abordant la maladie d’Alzheimer proposent une forme où le sujet peut se reconnaître et, ce faisant, réorganiser son rapport à lui-même et à la personne en face de lui.

Selon Sophie, nos souvenirs deviennent eux-mêmes des « fictions », car nous choisissons la manière de les raconter. Cette liberté narrative permet d’interroger l’objectivité du vécu. Schématiquement, on peut distinguer trois temporalités : d’abord celui de l’évènement vécu dans son immédiateté ; ensuite celui de la mémoire et de l’imagination « proto-narrative » (Schaeffer, 2020, p. 15[2]) qui la complète dans une manière de récit que l’on se fait pour soi-même ; enfin celui des œuvres littéraires et filmiques qui vient nourrir et parfois transformer notre manière de (nous) raconter. Le psychologue Cédric-C. Boven apporte à cette réflexion un lien au modèle psychanalytique : « raconter, dit-il, c’est donner forme à ce qui, à l’état brut, reste informe, inconnu, et donc sur lequel on ne peut pas agir. La mise en récit permet d’apprivoiser ce qui demeurait fuyant et douloureux, en rendant l’expérience cohérente ». Dans cette perspective, les récits deviennent une ressource précieuse, particulièrement lorsque la communication avec la personne malade n’est plus possible. Sophie insiste d’ailleurs sur ce point : ce qu’elle trouve le plus intéressant dans la fiction, c’est sa capacité de donner à voir ce qui se passe dans l’esprit de sa mère, alors même que celle-ci n’est plus en mesure de le dire, ni même de le comprendre.

Films et textes, images et mots sur la maladie d’Alzheimer sont autant de moyens permettant aux lecteurs et lectrices et aux spectateurs et spectatrices de plonger au cœur de l’expérience vécue par les malades et leurs proches, rendant palpable l’effacement progressif de la mémoire. Ils offrent des espaces pour combler les vides, réinventer les gestes et les pensées, reconnaitre et transformer l’expérience subjective. S’interroger sur les différences de chaque art et médium ouvre un champ de réflexion sur les rôles que ceux-ci peuvent jouer dans le quotidien de l’individu.

Bibliographie

Œuvres

ERNAUX, Annie, Une femme, Paris, Gallimard, 2022 (1988).

ROUMANOFF, Colette, L’homme qui tartinait une éponge : Mieux vivre avec Alzheimer dans la bienveillance et la dignité, Paris, Édition de La Martinière, 2018.

ZELLER, Florian (réalisateur), The Father, UGC, 2020, 97 minutes.

Travaux

BARONI Raphaël et PASCHOUD Adrien, « Introduction. L’héritage de Ricoeur : du récit à l’expérience », Cahiers de Narratologie, n° 39, « L’héritage de Ricoeur : du récit à l’expérience », dir. R. Baroni et A. Paschoud, 2021 : https://doi.org/10.4000/narratologie.12239.

PERETTI Pascale, « Mémoire et fiction : apports de la littérature à l’approche psychothérapique des troubles démentiels », Psychothérapies, vol. 36, n°3, « Parcours et mémoires », dir. Philippe Rey-Belley, 2016, p. 187-194 ; disponible en ligne : https://doi.org/10.3917/psys.163.0187.

RICOEUR Paul, Soi-même comme un autre, Paris, Seuil, 1990.

RICOEUR Paul, Temps et Récit, 3 vol., Paris, Seuil, 1983-1985.

SCHAEFFER Jean-Marie, Les Troubles du récit. Pour une nouvelle approche des processus narratifs, Paris, Thierry Marchaisse, 2020.

TALPIN Jean-Marc et TALPIN-JARRIGE Odile, « L’entrée en littérature de la démence de type Alzheimer », Gérontologie et société, vol. 28, n°114, « Vieillir dans la littérature », dir. Alain Montandon, 2005, p. 59-73 ; disponible en ligne : https://doi.org/10.3917/gs.114.0059.

Travail sur le podcast

Ingénieur du son : Léonard de Hollogne.

Musique à la guitare : Extraits du Prélude no 1 en mi mineur de Heitor Villa-Lobos et de l’Adagio de la sonate en sol mineur pour violon solo BWV 1001, interprétés par Ricardo Lopes Garcia.

Merci à Sophie pour sa confiance.

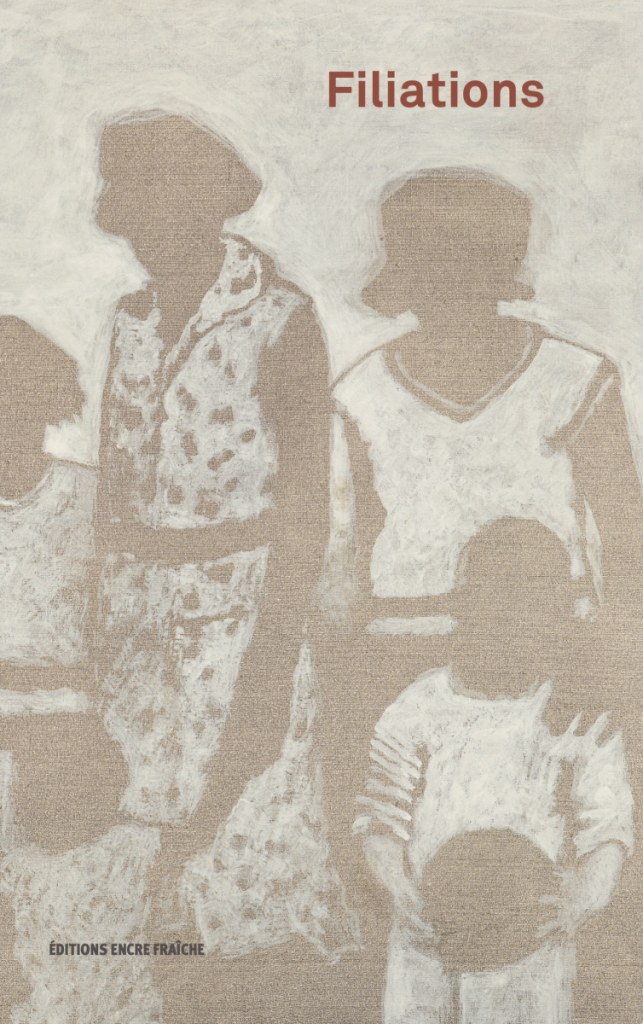

À propos de l’image de couverture

Le travail parle de la mémoire et de l’oubli. Des petites boîtes trouvées chez notre grand-mère. Des boîtes trop petites pour contenir quelque chose d’utile. À l’intérieur, des trésors d’enfants : une bille, du fil et une aiguille, quelques petits papiers, des petits objets inconnus. Ces boîtes, comme la maison de notre grand-mère, ont disparu. Restent des fragments, des petites coques vides, des tentatives multiples de captation d’un passé révolu. Ces boîtes deviennent des coquilles fragiles, réceptacle de ma mémoire d’enfant.

Et maintenant, avec cette porte en fer à la cave, j’ai toujours deux corbeilles, que je remplis avec, pas tout, mais mes trucs en étain, auxquels je tiens, je n’aurai plus le double, tu vois, je ne pourrai pas me le racheter. Et c’est des souvenirs.

Et alors je le mets là-dedans, je ferme la porte à clé, et je range la clé et ça, c’était pas un secret, et j’ai enlevé et je les ai mises dans un tiroir, là-haut, quelque part.

Deux clés, une petite et une grande.

(Jeanne Kapp, notre grand-mère, 2013)

[1] Cette notion, théorisée par Paul Ricoeur dans Temps et Récit (1983-1985), puis approfondie dans Soi-même comme un autre (1990), repose sur la capacité du sujet à configurer les évènements de son existence au sein d’un récit concordant et cohérent. La compréhension de soi passe alors par une interprétation de soi médiatisée par le récit. En se racontant, le sujet parvient à maintenir une forme de continuité et de cohérence, en dépit des changements et des discontinuités qui traversent l’expérience.

[2] Pour Jean-Marie Schaeffer dans Les Troubles du récit. Pour une nouvelle approche des processus narratifs (2020), la proto-narrativité renvoie à des formes narratives élémentaires, le plus souvent inconscientes, qui précèdent le récit structuré. Avant toute élaboration consciente d’une histoire cohérente, ces formes primitives de mise en récit, faites de mémoire épisodique, de ruminations, de rêves, d’imaginaire ou d’anticipation, contribuent à façonner l’identité, en reliant passé, présent et futur, sans passer par les schémas narratifs classiques.

![2clés edited copie (1)[53].jpg](https://wp.unil.ch/ateliercomparatiste/files/2025/12/2cles_edited-copie-153.jpg-1200x796.jpeg)