Stanley Jevons trained as a chemist at University College London in the early 1850s. He is known as one of the founders of the marginalist theory of consumer behaviour which has become part of the standard equipment of modern economics. Before turning to political economy in the 1860s, he worked for about five years as one of two gold assayers in Sydney for the newly created mint. He was recommended for the job by his cousin William Roscoe, himself a noted chemist.

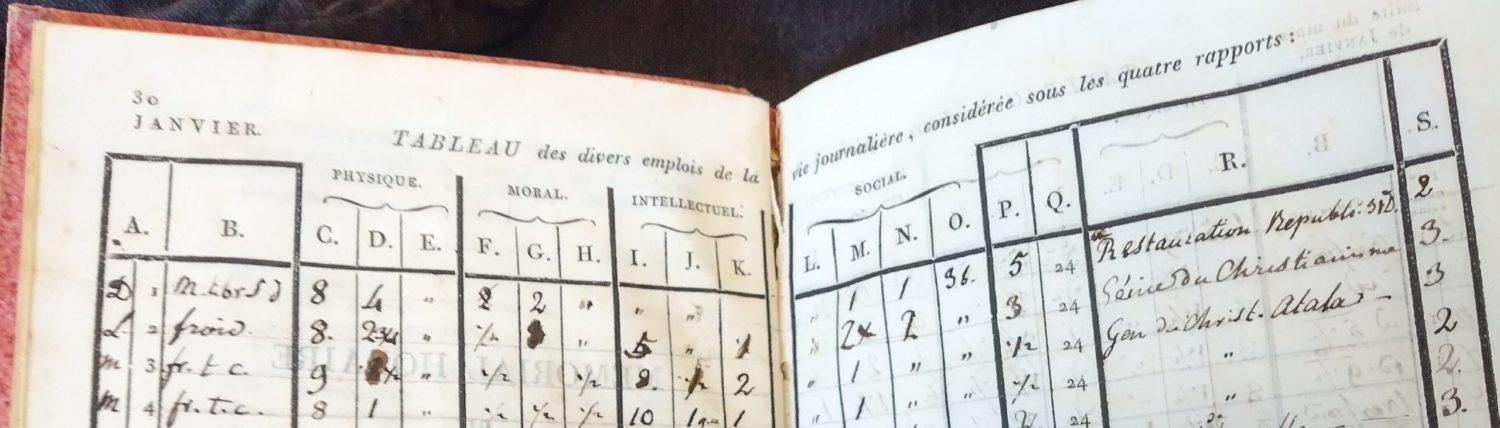

The two pages are taken from Letts' diary for 1855, which Jevons kept during his years in Australia. Jevons, then nineteen, had moved to Sydney. He writes the month at the top of the page, then draws two dividing lines for the days of the week. After making notes for one day, he draws a line to start the next. He does the same for the next two days, so that he can usually make notes for four days on two pages.

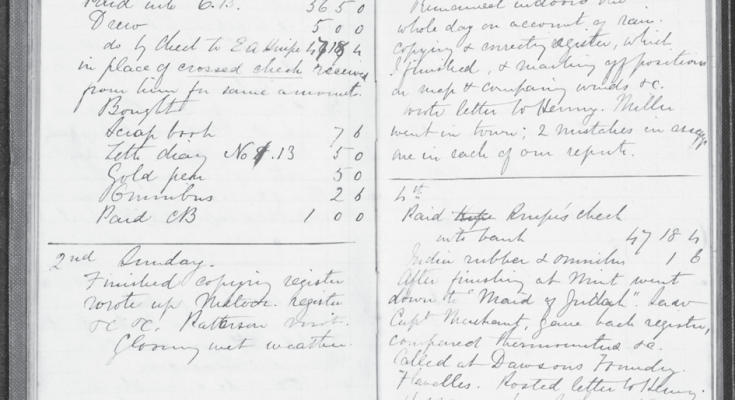

The entry for '1st December' shows financial transactions and payments made: among other things for Letts's diary for the coming year, for the omnibus he regularly takes to the Mint, and a large money transfer to his family in Britain. For the '2 December' entry, he copies a weather record he borrowed from the captain of the 'Maid of Judah', the ship that brought him to Sydney. He also mentions a visit and notes the weather. On the morning of 3 December he finishes 'copying and correcting' the weather record - elsewhere in the diary he notes that he is unhappy with its quality - and begins marking the data on a map for comparison. He also remarks on the errors found in the test reports that he and Charles Miller, the Mint's second tester, had written. On 4 December Jevons returns the weather record to Isaac Merchant, captain of the Maid of Judah, reads the thermometer, visits a merchant and posts a letter to pay for sheets. The entries are mentioned with an approximate indication of the time of day when they were written (morning, afternoon, evening).

This exhibition allows us to reconstruct in great detail Jevons' life during those four days: payments and social, scientific and professional activities. But for Jevons, it represents more than a record of his actions. Recording the borrowing of the meteorological register implies a promise to return it, which he did two days later. Recording that he has not finished copying a particular item means that he still has work to do - which must be completed before the ship sets sail again. Noticing mistakes at work implies a desire to improve. The payment of a cheque to the bank is the fulfilment of a financial commitment dated 1st December.

The diary moderates his social, financial, professional and intellectual life. It sequences his actions over time. It shows him who he is through what he does. His actions involve norms that are not stated or logically deduced. But they are implied in his actions. Sending money home, paying a debt, returning a borrowed register, marking mistakes, paying for clothes: such facts show him to be a diligent person who can be trusted and whom he himself can trust.