Par écrits personnels, on entend tout texte dans lequel une personne témoigne d’une prise de parole sur elle-même, sur son proche entourage ou sa communauté, ou, pour le moins, de jugements de valeurs sur le monde, proche ou lointain. En font partie entre autres, outre des notes hétérogènes non attribuables à un genre défini, les autobiographies, les journaux de toute nature, les récits de voyage, les livres de raison, les chroniques et les livres de famille. Quoiqu’appartenant également à ce corpus, les correspondances n’ont, à ce jour, pas été inventoriées dans Egodocuments.ch pour des raisons pratiques, pour autant qu’il ne s’agisse pas de copie-lettres, rédigés sur une certaine durée. Elles peuvent toutefois apparaître à titre de « sources annexes ».

+

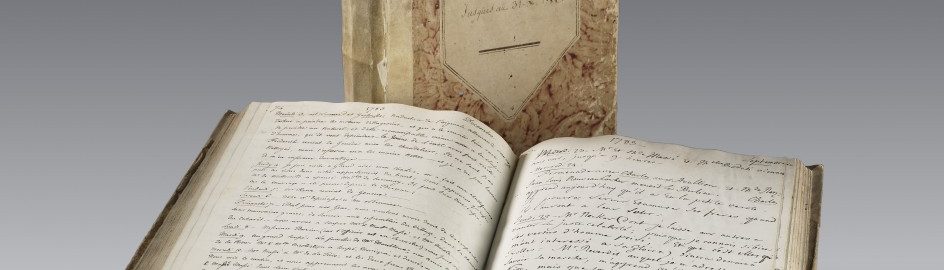

La notion d’écrits personnels renvoie pour l’époque moderne à différents genres de textes, qui témoignent de pratiques diversifiées d’écriture dans des temporalités variables, tels un journal écrit au jour le jour, des mémoires rédigés au grand âge, ou encore un livre de famille, tenu sur plusieurs générations. Parfois ces genres s’interpénètrent : une chronique, par exemple, peut se transformer en journal, ou inversement. Il s’agit de textes généralement non destinés à la publication.

A l’échelle européenne, la notion d’écrits personnels est l’une des terminologies retenues parmi d’autres, qui ont valeur de synonyme dans différentes langues, et qui toutes prêtent à discussion : écrits du for privé [1], Selbstzeugnisse, scritture del sè, 1st person writing, autobiographical writing [2], ou encore egodocuments [3, 4], qui a l’avantage de pouvoir s’utiliser dans toutes les langues.

Le débat reste ouvert quant à la question de savoir exactement quels types de textes la notion d’écrits personnels englobe ou non. On a ainsi questionné notamment la légitimité d’y inclure ou non, au vu de leur caractère « non volontaire » les témoignages devant les tribunaux [5], les textes autobiographiques rédigés dans un cadre institutionnel (ecclésiastique, en particulier), et donc également prescrit [6], ou, en raison d’une faible thématisation du « je », les chroniques à caractère principalement événementiel [7, 8, 9].

La tendance actuelle de la recherche est à l’élargissement de la catégorie [10], l’aspect personnel (soit un point de vue individuel, certes jamais libre d’influences mais comportant des jugements de valeur identifiables) ayant acquis autant d’importance que la dimension strictement autobiographique (discours d’un individu sur lui-même et ses proches). Une tendance renforcée par l’élargissement de la recherche au-delà de l’aire européenne, qui impose la prise en compte d’autres modalités d’expression autobiographique [11]. Même le discours rapporté, étudié notamment dans le cas de l’empire ottoman, pourrait, à certaines conditions, entrer dans la catégorie des écrits personnels [12].

Références

[1] « After ten years, I am not sure anymore that the term, we are using, in France is wholly appropriate. It tends to reduce the texts we want to study together, to just one of their dimensions, that one which paves the way towards the construction of modern self, which is a simplistic view. Like Kaspar von Greyerz, who has criticized the notion of ‘egodocuments’, I am coming to the conclusion that the term ‘écrits du for privé’, although effective in the French context, obscures more than it helps communication on an European scale. », François-Joseph Ruggiu éd., « The Uses of first Person Writings on the ‘Longue durée’ (Africa, America, Asia, Europe)», in F.-J. Ruggiu éd., The uses of first Person Writings (Africa, America, Asia, Europe), Bruxelles etc., Peter Lang, 2013, p. 11.

[2] « I define autobiographical writing as any literary work that expresses lived experience from a first-person point of view. […] I realize that this is a problematic approach, especially since « autobiography » in this sense embraces so many forms that are, strictly speaking, not autobiographical. » James Amelang, The Flight of Icarus. Artisan Autobiography in Early Modern Europe, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1998, p. 47.

[3] « In the early 1950s the historian Jacques Presser invented a new word : « egodocument ». He proposed to use his neologism for diaries, personal letters and other forms of autobiographical writing […] those documents in which an ego intentionally or unintentionally discloses, or hides itself. Texts in which an author writes about his or her own acts, thoughts and feelings would be the shortest definition.» Rudolf Dekker, Egodocuments and History, 2002, p. 7.

[4] « The historical subject we can grasp within and behind the autobiographies, diaries and family chronicles on offer is not an ego. It certainly has a self, whose external contours of personhood some of the documents in question may allow us to study. For all practical historical purposes, what we are looking at in self-narratives are primarily persons in their specific cultural, linguistic, material and, last but not least, social embeddedness. Ultimately a majority of these texts, most certainly early modern ones, probably tell us more about groups than they do about individuals.[…] It may well be too late to stop the current rise in interest in the notion of ego-documents, although it seems unlikely that this will do justice to most early modern self-narratives. The category appears to be universally recognized, and even many specialists seem to assume that a cath-all basket is better than a more narrowly defined category.» Kaspar von Greyerz, «Ego-documents: The Last Word?», German History 28/3, 2010, p. 281.

[5] « Darunter [= unter Ego-dokumente] sollen alle jene Quellen verstanden werden, die uns über die Art und Weise informieren, in der ein Mensch Auskunft über sich selbst gibt, unabhängig davon, ob dies freiwillig – also etwa in einem Brief oder in einem autobiographischen Text – oder durch andere Umstände bedingt geschieht.» Winfried Schulze, Ego-Dokumente, 1995, p. 10

[6] « On entend par écrits du for privé livres de raison, livres de famille, diaires, mémoires, autobiographies, journaux de toute nature (personnel ou « intime », de voyage, de campagne, de prison…) et de manière générale, tous les textes produits hors institution et témoignant d’une prise de parole personnelle d’un individu sur lui-même, les siens, sa communauté. » www.Ecritsduforprive.fr/presentation.htm

[7] « Das « denckh Büechlin », das die Priorin Verena Reiterin vom Kloster St. Wolfgang in Engen um 1653 geschrieben hat, ist zunächst nicht als Selbstzeugnis zu bestimmen. Über mehrere Jahrzehnte berichtet sie nach Angaben ihrer aus Krankheitsgründen resignierten Vorgängerin und vermerkt sogar ihren eigenen Klostereintritt nur pauschal. Im letzten Teil dieser kleinen Chronik jedoch tritt die Schreiberin mehr und mehr hervor, vor allem in kritischen Situationen. Sie nennt sich zwar in der Regel mit Namen und fügt nur selten ein Ich hinzu, aber nimmt ausdrücklich auf ihre spezifische Lage Bezug. Wir erfahren von ihren Krankheiten, ihren Ängsten, ihren Fluchten, ihrem zupackenden Eingreifen und von der prekären Lage, in die sie gerät, als sie unter Mißachtung der freien Wahl erst zur Subpriorin und später zur Priorin erhoben wird. Benigna von Krusenstjern, «Was sind Selbstzeugnisse? Begriffskritische und quellenkundliche Überlegungen anhand von Beispielen aus dem 17. Jahrhundert», Historische Anthropologie, vol. 2, No 3, 1994, p. 466.

[8] « Savoir si la chronique est autobiographique ou non implique que l’on tienne compte des modalités d’expressions de la vie individuelle propres à la période et au groupe socio-économique auquel appartient le chroniqueur. L’élément autobiographique est, nous semble-t-il, composite. Loin de se limiter au seul parcours de vie, il peut apparaître sous forme d’étapes particulières de ce parcours – peut-être secondaires à nos yeux, mais pas à ceux de l’auteur – et par le biais des opinions personnelles exprimées par ce dernier dans un moment et un contexte donnés où il aurait pu agir. Il ne paraît pas par ailleurs devoir être limité aux apparitions d’un « je » agissant. Ile se manifeste aussi dans la manière de présenter les faits, que le jugement soit implicite ou explicite.» Danièle Tosato-Rigo, La chronique de Jodocus Jost, miroir mental d’un paysan bernois au XVIIe siècle, Lausanne, Société d’Histoire de la Suisse Romande, 2000, p. 187.

[9] « Readers frequently inscribed almanacs with handwritten notes, and this kind of interaction between manuscript and print might plausibly be the most common form of sel-accounting in early modern England, played out around the edge of countless almanacs.» Adam Smyth, Autobiography in Early modern England, Cambridge, 2016 (12010), p. 19.

[10] « Selbstzeugnisforschung works with a more open understanding of sources and genres. Aside from diaries, memoirs and autobiographies, numerous other texts can count as self-narratives, such as letters, chronicles, family histories, travelogues, biographical dictionary entries or diplomatic records.» Gabriele Jancke, Claudia Ulbrich, « From the Individual to the Person », in Mapping the I…, Leiden, 2015, p. 18.

[11] « In reality, in Arabic texts of the period 1500-1800, we can find self narratives incorporated in a variety of different genres. We find them in literary works and belles lettres; we find them in academic writings such as histories, chronicles and dictionaries. And of course they ca also be found in travel books and in the more personal genre of letter writing. In fact, except fort he religious sciences – studies of jurisprudence, of prophetic traditions and so on, writings which followed strict academic rules – almost every type of text was open to intervention from the ‘I’ author.» Nelly Hanna, «Self Narratives in Arabic Texts 1500-1800», in J.-F. Ruggiu éd., The uses of first Person Writings (Africa, America, Asia, Europe), op. cit., p. 142.

[12] « The limits of the genre [= Ego-Documents] should be drawn generously in order to allow for more texts to be included, texts that have come to light in the last thirty years – often quite unexpectedly – and were sometimes quite difficult to assess. With this in mind, I will analyze a short treatise (risale) that displays a particular constellation of several first-person narratives interlaced with third-person passages. The “Menakib-i Sheykh Mehmed Emin Tokadi” (Vita of Sheykh Mehmed Emin Tokadi) reflects the life and thought of Sheykh Mehmed Emin Tokadi (1664–1745), one of the more influential sheykhs of the 18th century Nakshbandiyya order of dervishes. One of his disciples, Seyyid Yahya Efendi (1711–1784), wrote down Mehmed Emin’s pronouncements – in first person singular – but was not able to finish the work. One of his disciples, Seyyid Hasib Üsküdari (d. 1785–86), took over and wrote down the entire Vita.» Barbara Kellner-Heinkele «The Pearl in the Shell: Sheykh Mehmed Emin Tokadi’s (d. 1745) Self-vita as scripted by Sheykh Seyyid Hasib Üsküdari», citée par Selim Karahasanoğlu, «Learning from Past Mistakes and Living a Better Life: Report on the Workshop in Istanbul on Ottoman Ego-Documents», Review of Middle East Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Décembre 2020), p. 299.

Danièle Tosato-Rigo, 2025