In recent years, scholarly attention has been overwhelmingly directed toward cataphatic or affirmative traditions of contemplation and mysticism in late medieval England. Frequently containing strongly visual and affective elements, these traditions start from the premise that a number of qualities can be affirmed about God: his nature as love, his goodness, the possibility of his apprehension through the spiritual senses etc. Most of the members of the small group misleadingly homogenised in modern times as ‘The Middle English Mystics’, utilise these traditions to a greater or lesser extent. Richard Rolle hears divine melody and burns with a flame of love; Julian of Norwich uses a vision of Christ crucified as a vehicle for new insights about God’s bond with humankind; Margery Kempe disturbs contemporary audiences with her performances of affect in response to Christ’s passion, and even Walter Hilton focuses on a divine image hidden within the soul which needs to be sought out and restored. All these writers have received extensive critical attention over the last twenty-five years. The two women mystics have each had monographs and ‘Companion’ volumes of essays devoted to them, as well as dedicated conferences focused upon their writings. They have also been the subject of a range of contemporary creative and devotional responses. By the same token, the Yorkshire hermit Richard Rolle, one of the most prolific and widely-copied writers of the late Middle Ages, has also attracted considerable attention, forming the principal subject of several important monographs.

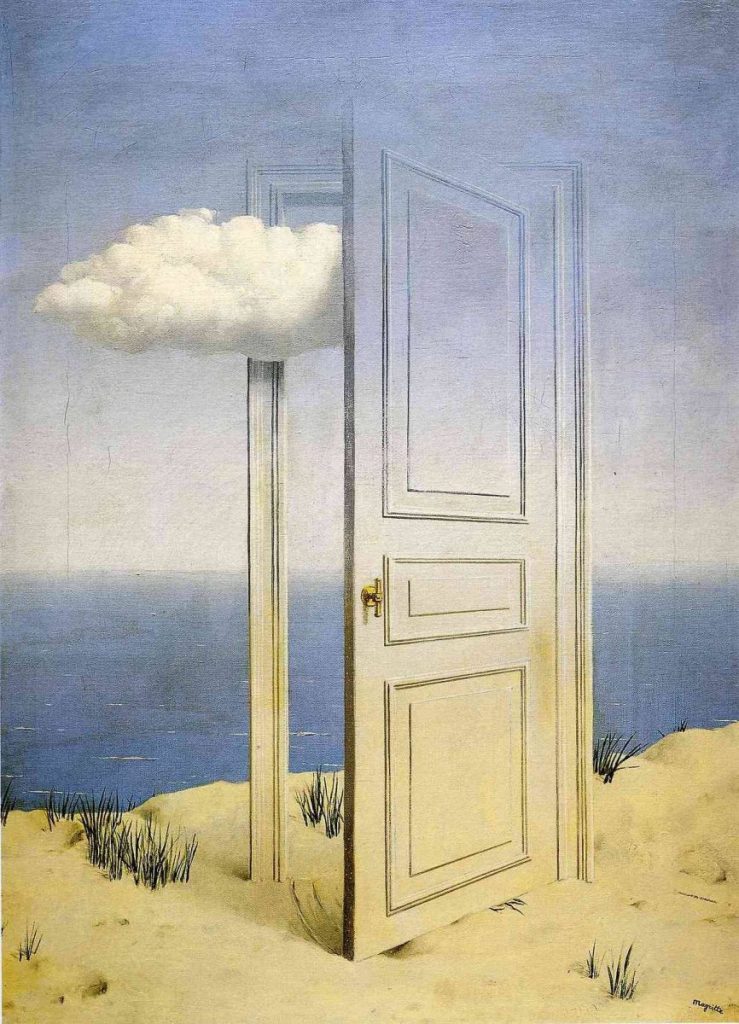

However, running alongside this tradition of cataphatic mysticism, is a second contemplative tradition, termed apophatic or negative, which seeks to erase sensory perceptions and to strip away all that can be known about God, leading the disciple instead toward a place of darkness and cognitive obscurity. This tradition, ultimately derived from the writings of the sixth-century Syrian, Pseudo-Dionysius, long believed to be the Athenian convert of St Paul, has received much less attention within English medieval studies despite its profundity and sophistication. Its main exponent in Middle English is an anonymous author known as the Cloud-author, probably a Carthusian from the north-east Midlands, who wrote an ambitious contemplative work titled The Cloud of Unknowing, together with five shorter treatises, including a Middle English translation of Pseudo-Dionysius’s Mystica theologia, developing his specialised theology in various directions. Although excellent editorial work has been undertaken on these treatises, along with various translations into modern English, astonishingly no largescale critical work has been published for almost twenty-five years, and they have rarely formed the focus of scholarly discussion and collaboration. By the same token, the net has not been broadened to consider the possibility of an English apophatic tradition, within which the Cloud-author plays a key but by no means singular role.